Merritt Kopas is the author of over two dozen digital games, including Consensual Torture Simulator, HUGPUNX, and LIM. In 2014, she was named one of Polygon's 50 Admirable People in Gaming. She is from southern Ontario and the Pacific Northwest and currently lives in Toronto with her cat ramona. She's been using Twine since she started making videogames in 2012. She currently runs the podcast Woodland Secrets at http://woodlandsecrets.co.

Taken up by nontraditional game authors to describe distinctly nontraditional subjects—from struggles with depression, explorations of queer identity, and analyses of the world of modern sex and dating to visions of breeding crustacean horses in a future gone wrong—the Twine movement to date has created space for those who have previously been voiceless within games culture to tell their own stories, as well as to invent new visions outside of traditional channels of commerce.

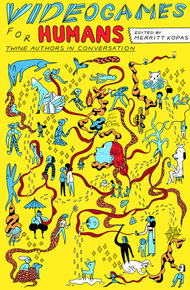

Videogames for Humans, curated and introduced by Twine author and games theorist merritt kopas, puts Twine authors, literary writers, and games critics into conversation with one another's work, reacting to, elaborating on, and being affected by the same. The result is an unprecedented kind of book about video games, one that has helped to jumpstart the discussions that will define the games culture of tomorrow.

Featuring contributions from: Aevee Bee, Alex Roberts, Anna Anthropy, Auriea Harvey, Austin Walker, Avery Mcdaldno, Benji Bright, Bryan Reid, Cara Ellison, Cat Fitzpatrick, Christine Love, Elizabeth Sampat, Elizabeth Sampat, Emily Short, Eva Problems, Gaming Pixie, Imogen Binnie, Jeremy Lonien & Dominik Johann, Jeremy Penner, John Brindle, Katherine Cross, Kayla Unknown, Lana Polansky, Leigh Alexander, Leon Arnott, Lydia Neon, Maddox Pratt, Mary Hamilton, Matthew S. Burns, Mattie Brice, Michael Brough, Mike Joffe, Mira Simon, Naomi Clark, Nina Freeman, Olivia Vitolo, Patricia Hernandez, Pippin Barr, Riley MacLeod, Rokashi Edwards, Sloane, Soha Kareem, Squinky, Tom McHenry, Toni Pizza, Winter Lake, Zoe Quinn.

"An inspiring, thought-provoking book which twins walkthroughs of Twine text games from a multitude of collaborators with creative, cutting - sometimes autobiographical - commentary from diverse authors." – Simon Carless

"Thanks to tools like Twine and to a vigorous creative scene, alternative creators have seized control of that creaky word, hypertext, hybridized it with the videogames they grew up loving, and have turned it into a powerful, in-your-face, diverse, exciting field. Voices we have never heard before. Experiences we have never had before. Art that, well, hasn't been arted before. And here it is, reflected back at you through playthroughs by some of the most interesting writers in games. There is no better snapshot of the scene as it stands than this book."

– Raph Koster, author of A Theory of Fun for Game Design and designer of Ultima Online"With each chapter in Videogames for Humans I immediately felt a specific kind of affectation I often associate with Twine games—contemplative, slow, mysterious and exciting. These are games that often beg for reflection and context, and it's apt that artists working in a medium as seemingly antiquated as interactive fiction are developing works of digital play and storytelling with such depth."

– VICE Motherboard"[Twine] attracts a delightfully broad pool of creators, giving voice to underrepresented, atypical and also more conventional voices . . . Videogames for Humans contains fascinating conversations."

– The Guardian1. me

I've been trying to think of a way to phrase this that won't sound over the top, but I can't. So here it is:

Twine changed my life.

I know, I know. But hear me out.

When I first encountered Twine I was a graduate student in my early twenties. I went into grad school right out of college, which I went into right out of high school. It wasn't totally bad. I liked getting to read so many books, and getting to talk with clever people. But a couple of years in, I was beginning to realize that something wasn't right. Without sitting down and planning on it, I'd been an academic for my entire adult life. I felt trapped, like I'd gotten on a train and drifted off, and now it was speeding along the tracks of my life so fast that I'd never have a chance to disembark.

Listen: I had been dissociating for so much of my life that academia was easy for me, because it let me distance myself from the subjects of my writing. It let me interpose layers of interpretative analysis between myself and my experience. And those layers functioned as protective barriers, keeping me safe from any unfiltered contact with reality. I wrote paper after paper about queerness and bodies, but I wasn't writing about myself, not really—at least, that's what I told myself. I couldn't write about me, because to do that would mean tearing up boarded-off places in memory and really acknowledging what my life had been like up to that point.

And then I discovered Twine.

The first time I ever played a Twine game I was confronted with this text:

If there's one thing Encyclopedia Fuckme knows - and this is a hypothetical statement, of course, because she's actually got a lot crammed in her big fat brain - it's how to get off! But in addition to her brain, our hero also has a very greedy pussy - one that sometimes leads her into trouble! Such is "the case" today. But if she does what she does best, she just may solve . . .

THE CASE OF THE VANISHING ENTREE.

Fuck.

This was 2012, and I hadn't ever seen writing like that in a videogame. I'd grown up with games, but I'd never felt the presence of their authors. Games were, to me, cultural products similar to big-budget films: Obviously there were people involved in their design, but they never came through as individuals. And although by 2012, I was dimly aware of the existence of independent artists who made their presence as individual human beings felt through games, my experience had led me to believe that even those creators were mostly men, telling stories that were maybe interesting but not directly relevant to my life.

And then, this: Anna Anthropy's Encyclopedia Fuckme, a game about a clever lesbian with a submissive streak trying to avoid becoming her seductive cannibal date's dinner.

Maybe it's tipping my hand too much to say this game spoke to me, but it did. It was everything I had been led to believe videogames weren't, couldn't be: funny, hot, relevant to my life. And there were more. There were people writing in ways that resonated with me, about things I didn't even know I needed to see written about. I started devouring Twine works wherever I could find them, building up a renewed appreciation for interactive fiction and digital games.

It was a while before I worked up the courage to write my own story in Twine. I was self-conscious, unconfident in my abilities. It was a struggle trying to write something outside of an academic, analytical mode for the first time in years—looking back, even my personal blog posts at the time were intellectualizing. But I fought through it and ended up writing a piece for a partner I was with at the time, a game called Brace, meant for two people to play together and about struggle and perseverance against a hostile world. It wouldn't be the last time I used Twine to write a game as a gift for somebody I cared about: Months later, I wrote a game for distant friends on New Year's Eve (Queer Pirate Plane) and a short piece mixing personal narrative and sex education for a lover (Positive Space).

It was like a floodgate broke. For the next year, Twine was the main outlet through which I processed my emotions, working through personal and political struggles by making something out of them. I made works about family, love, sex, bodies: things I'd never been able to examine directly before. I made a game about difficult talks with my mother; I made a game about childhood abuse; I made a game about consensual sadomasochism.

Hell, I made a game about muffing, an underground sex act popularized through a zine, and it got coverage on mainstream videogame sites.

What was it that made Twine special for me? I think that something in the form of it, its presentation of nodes and links, felt less intimidating than the blank page and blinking cursor of a word processor. Somehow it felt more inviting. It didn't demand, as that blank page seemed to, that I tell a linear story, one that was neat and made sense and contained some kind of resolution. Of course, there's nothing about traditional text that demands any of these things either. But I'd been writing in an analytic mode for so long that I couldn't look at a blank page without my mind struggling to put things in order before I got a single word down. When I opened up Twine, I felt free to just start writing fragments, each in their own passage. The connections could come later.

Most importantly, I was able to share these works with other people like me. Twine brought me into a network of people who made games outside of the mainstream. On Twitter, we made connections, shared techniques, built friendships and informal collaborations.

Late 2012 and early 2013 was an extraordinarily exciting period for me: I started, for the first time, to feel like I was a part of something. The "queer games scene" covered by videogame outlets might not have been as cohesive as some accounts supposed, but for a little under a year, it definitely felt real. We were telling new stories in new ways, stories that were not just unheard of as subjects for videogames—which they certainly were—but rare in any medium. We were writing about messy lives on the economic and social margins of society, about the complexities of embodiment and community, about our grotesque cyberpunk dreams and gay pulp fantasies.

Things fell apart, as they often do in tightly knit, passionate communities of artistic people with few resources—especially when those people are all also friends, lovers, or something in between. But that period was intensely generative, launching a number of authors into visibility and recognition and solidifying the reputations of others. When the burst of activity around Twine during this time ended, it didn't just fizzle out—it left marks on literary and independent videogames communities.

Twine games ended up on college syllabi, technical resources piled up for those wanting to play with variations on the form, and even the relatively small amount of journalistic and critical attention paid to some prominent Twine works raised the profile of the tool to a new level. When Richard Hofmeier—winner of the 2013 Independent Game Festival's grand prize award for his game Cart Life—defaced his own booth and replaced his game's demo with Twine author Porpentine's well-received game Howling Dogs, it became impossible to ignore the importance of Twine to independent games.

Of course, we shouldn't overstate that importance. A very small number of authors gained visibility during this period, and almost all of them still struggle with material insecurity. Independent videogames is a notoriously competitive field, one in which a very few people do extremely well while everyone else just tries to get by. Twine authors, being on the margins of an already marginal field, struggle to do even that. The mainstream videogame industry prides itself on being on the cutting edge of technology, for better or for worse. And as Twine work generally doesn't involve high-definition graphics or immersive three-dimensional worlds, Twine authors continue to find themselves defined out of videogames and denied coverage or critical attention in favor of more graphically appealing or lucrative works, while mainstream videogames are just beginning to develop richer narrative techniques and are receiving heaps of praise and money for it.

This is what an artistic revolution looks like: some people get a little famous, nobody gets rich, and years later, people who have more resources than you steal your ideas and use them to get richer and more famous than they already were.

But the thing about artistic revolutions is that people keep working long after the mainstream has moved on to its next fascination. It's 2015, years out from the "Twine revolution," and people continue to produce powerful, unique works with the tool.

And ultimately, Twine's importance goes beyond the work produced by the most visible, recognized creators. Twine showed me that people who weren't interested in becoming "game developers" or "game designers" themselves could use games to tell important, personal stories.

Once I started using the tool, it wasn't long before I started running Twine workshops at schools, conferences, and community spaces. Most memorably, I co-ran a Twine workshop with Anna Anthropy at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit in 2013. The participants included an elderly local man and a mother with her toddler daughter, each of them excited to use the medium to tell their stories in a new way. As Ian Bogost describes in his book How to Do Things with Videogames, we're approaching a reality in which people like our workshop participants can use videogames in the same way as they might use a digital camera. We're not quite there yet, but it's exciting to see the form enlarging and expanding, shifting away from a specialized media produced by and for a narrow audience and toward a range of new shapes and contexts.

It's been a huge privilege to be a part of that. In 2012, I was a depressed, impoverished academic. Writing this, in early 2015, I'm still not exactly well-off, and I wouldn't say I'm the most mentally or emotionally well person around, but I have work I'm proud of and networks of friends and colleagues I've met through making it. I've ended up in a place I couldn't imagine I might when I sat down and played that first Twine game a little over two years ago.

But this book isn't about me, not really.

2. twine

Okay. So what is Twine? For most people, the easiest parallel is to Choose Your Own Adventure books. You know, those books that were popular in the 80s and 90s that presented you with some kind of fantastical narrative along with a list of choices. Like, you're confronted with a weird potion: If you'd like to drink it, turn to page 60; if that sounds like a terrible decision, turn to page 251. These branching narratives were a neat mutation of the textual form of the book, though they mostly remained marginal in literature and were generally marketed only to young readers.

Twine is kind of like that, in that it's a tool you can use to create branching narratives. More broadly, it's a tool for creating hypertexts, collections of passages joined by links. A typical Twine story looks like a textual webpage, and the player generally advances through it by clicking textual hyperlinks. This is one of the great attractions of Twine: playing a Twine game draws on familiar skills. Unlike contemporary videogames, which require the player to navigate bewildering fictional three-dimensional spaces and complicated control schemes, anyone who can navigate a webpage can play a Twine game.

Because of that use of familiar skills, the games produced with Twine are at root far more accessible than most contemporary videogames (though I'll have more to say on this later). As a tool, Twine is more accessible than most game design environments too. Interestingly, this accessibility is partly because Twine's development environment isn't strictly textual. Whereas traditional game design requires the designer to be able to write and understand lines of purely textual code and to visualize the in-game results, Twine's development environment presents the prospective designer with only two core elements: passages and links. To create a passage, it's only necessary to write it, and then any text within the passage can be turned into a link. These passages can be dragged and shifted around the screen, with links between passages represented by arrows, creating a kind of flowchart. Thus it's easy to track branching paths as you build by following the trail of arrows through the narrative. You don't really need to understand the logic of code to make something in Twine, but at the same time, Twine's logical flowchart environment makes it easy to pick up the basic principles that make up more complex structures of code.

Finally, since its creation by Chris Klimas in 2009, Twine has been free for anyone to use and modify, whereas many other game development tools require potential designers to purchase licenses running in the hundreds of dollars.

Twine started as a desktop application. In 2014, Chris Klimas and Leon Arnott released Twine 2 as both a desktop and web application. Crucially, though, Twine 2 continues the original's ideals of accessibility and user control. All user work is still saved locally on user computers, so there's no dependence on centralized servers or services. In the context of this period in which tool creators such as Adobe and Google are shifting to subscription-based models with the purpose of getting users invested in their "ecosystems" and thus fostering dependent relations between tool users and developers, Klimas and Arnott's commitment to user control is more important than ever.

Twine's financial and technical accessibility are major reasons for its broad adoption, especially among economically marginalized, nontraditional game designers—i.e., people who are not white men with college-level programming training. As a result, Twine has been the site of an incredible artistic flourishing at the intersections of digital games and fiction: a rebirth of hypertext. People who might never otherwise make a videogame make them with Twine. Some of these people have taken the skills they develop in using Twine and branch out to other forms and media; others have delved deeper into Twine itself and done things with it that nobody expected; and still others use it to make games that tell stories without the intention of becoming a professional artist or designer, just as one might write a poem or take a photo without needing or wanting extensive training in either of those skills. Authors can use Twine to create choose your own adventure stories, or interactive poetry, or nonlinear essays, or anything composed of sections of text and connections between them. Theoretically, authors could also use a word processor or pen and paper to create those texts. But there's a key difference between traditional writing tools and Twine: Twine simplifies the process of creating digital texts rather than analog ones, and it includes tools that allow Twine authors to conceal the rules and structure of their works from the reader. For example: In a choose-your-own-adventure book, the reader can page through to find the various endings or skip ahead to other segments, and the reader often has to keep track of states relevant to the game (how many weird potions she's carrying, for instance.) Twine keeps track of these states as the author directs, and it doesn't necessarily tell the reader it's doing so. Thus Twine games are often opaque, only revealing their full shapes to the player over the course of the narrative and sometimes not entirely at all.

Actually, this is one of the interesting things about digital games versus analog games as a whole. Think about a board game or a physical sport: You and the other players (or referees) are responsible for keeping the rules. But in the case of a digital game, the author dictates the rules through code, and the computer then enforces those rules while you're playing. You don't have to imagine or keep track of how far Pac-Man moves per second or what happens when a line of Tetris pieces forms; the game constantly tracks these things for you and tells you what happens as a result of your actions. And the game can track them without you even knowing it's happening, so there's the potential for surprise.

Thus Twine readers/players can experience a narrative in a way that would be difficult or impossible to reproduce on paper. Twine games can track how long we've lingered on particular decisions, remember the decisions we've made, and shift the later narrative accordingly without our necessarily being able to perceive a direct connection between our actions and the results. Take a game like Gaming Pixie's Eden, which mixes random events, player decisions, and tests of reaction time to create a feeling of urgency and risk, or Tom McHenry's Horse Master, which openly tracks a number of statistics for the player while also secretly managing others that affect the course of the narrative in the background.

But the possibilities go beyond digital ruleskeeping, allowing Twine works to go beyond a simple emulation of paper-based texts. In Michael Brough's scarfmemory, for example, hyperlinks function as parentheticals, unfolding diversions and side notes in the narrator's internal monologue, adding to, revising, and complicating his recollections as the narrative progresses, turning the experience of reading the game into one that spirals inward rather than moves forward.

In Bryan Reid's for political lovers, a little utopia sketch, clicking on links cycles the text through a series of possibilities—occupations, places, dreams—that reflect the hopeful tone of the work. Clicking the verbs in certain sentences cycles them through a dreamy set of options: translating, training dogs, becoming an astronomer, growing vegetables, building houses, and on and on.

Finally, in Christine Love's Even Cowgirls Bleed, the cursor itself becomes the crosshair of the player character's touchy gun. The player has to carefully navigate the cursor around the screen—learning the first time that she mouses over a link that her gun will go off at the object or person the link names, whether she wants it to or not. This transforms the usually relaxed, almost thoughtless activity of pointing and clicking a mouse into a deliberate, careful physical interaction with the text of the story.

To put it simply: Authors are doing things with Twine that aren't possible with traditional text. And at the same time, they're using interactive media to tell stories that mainstream videogames couldn't dream of telling. Thus far, this double innovation has made Twine hard to classify, which has left it without a home or much support from either literary or videogame communities. This book is an effort to change that.

3. this book

Twine is unique because it is at once a medium, form, and community. People use it to do wildly different things, and individual creators may never come in contact with one another. Yet we can still trace connections between their work.

This is a book about that work, as well as the communities, networks, and individual authors that have developed around Twine. It's about putting them into conversation with one another and with more established literary communities, because the works that they're creating are exciting, experimental, and worthy of sustained consideration. By finding stories we can tell about those works and those people, we can provide that consideration.

For example: Many of the figures who have risen to prominence in Twine circles are trans women. That trans women are recognized as the leaders of an artistic scene is a fact worth appreciating in its own right. But these authors' recognition should also be considered in the context of the emergence of new transgender literatures in the early 2010s, as represented by books like Imogen Binnie's Nevada and Casey Plett's A Safe Girl to Love. These texts are the result of trans people wresting their stories back from non-trans publishers and audiences, telling stories about themselves for other trans people. The work being done by trans women authors in Twine needs to be seen as a part of this movement, and is just one example of how critical work is emerging in Twine communities in parallel with broader literary developments.

What other kinds of stories can we tell about Twine?

There's the story of Twine as the focal point for the "personal games" movement of 2012-2013, catalyzed by Anna Anthropy's critical text Rise of the Videogame Zinesters. This story's been told before in different ways, positioning Twine as a truly accessible tool, the focal point for the growth of a community and the rise of a number of nontraditional authors in games. But there are elements of the story that people have left out, including the rapid pushback by traditional gamers and Twine's relegation to marginalized status both because of the intrinsic accessibility traditional gamers saw it as representing and because of its cultural association with nontraditional authors.

We could tell the story of the mostly invisible labor that's gone into the design and modification of the tool, the support work that's enabled the creation of all of the works that appear in this book. That story hasn't really been told yet, but it's an important one. We tend to privilege people who create flashy, visible products over those who do the work that enables that production. Support work is invisibilized, feminized labor, and there's a rich story to be told about the work that's gone into making Twine into what it is today. (Leon Arnott is our fairy godmother.)

Finally, we could tell the story of Twine as the rebirth of hypertext after its decline in the 90s, as well as the repopularization of interactive fiction after its relegation to mostly niche status. Interactive fiction has always had rich, dedicated communities, but parser-based interactive fiction shrank in popularity in the 1980s, after it became cheap and easy to generate digital graphics. Twine represents a broader resurgence of interest in interactive fiction, and it's indirectly led to the development of other tools for producing this kind of work.

We could have told any of these singular stories about Twine—as phenomenon, as platform, as medium. But in putting this book together, it didn't feel right to pick any one of them. Instead, we wanted to tell a number of stories by showcasing the actual works people have created with the tool—and the reactions actual people have had to those works.

Here's the thing, though: Twine's been used by a lot of people to make a lot of work. Go to Twinery.org and scroll through the lists of games: There are hundreds, maybe thousands. Some of these are by prolific writers whose names are well known, whereas others are made by people who gave the tool a shot and might never touch it again. The collective output of Twine users represents a bewildering spread of stories, kinds of authors, and approaches.

By necessity, then, any collection of Twine works is going to be partial. So how did I select the works that appear here?

Most of all, I wanted a wide range: of authors, content, and forms. The works in this book include interactive poetry, traditional choose-your-own-adventure games, therapeutic experiences, personal essays, and elaborate jokes. And their authors are similarly varied: Most don't fit into the traditional game designer profile of a straight, white man (though there are some of those, too).

Finally, the subjects of these games cover topics that mainstream games have still, in 2015, hardly touched. Partly, this speaks to the freedom afforded individual artists who aren't working to create a multi-million dollar product in the context of the massive entertainment industry of contemporary videogames. But partly, I think it also speaks to the ways that the medium of interactive fiction is suited to exploring themes that graphical games—for all their high-definition visuals and incredible technology—still have trouble with.

For instance, digital games have a hard time with sexuality. Maybe it's hard for designers to translate physical intimacy into a medium that's historically been mainly concerned with competition, or maybe it's an issue with the technical challenge of graphically depicting living bodies in a way that doesn't look comical or grotesque. Regardless, narrative text-based games are uniquely positioned to explore sex in a way that many larger-scale graphical games can't. Games like Benji Bright's Fuck That Guy, Olivia Vitolo's Negotiation, Cara Ellison's Sacrilege, Soha Kareem's reProgram, and Gaming Pixie's Eden get into themes of consent, sexual identity, and cruising, whereas mainstream videogames have only recently gotten past the inclusion of monogamous same-sex partnerships.

More generally, a lot of the work in this book challenges digital games' traditional elision of the body and emotions. Whereas in most mainstream games, protagonists have unfailing, untiring machine bodies and exhibit little to no emotional expression, the characters and roles in the games in this book have physical and psychic weight. Twine has occasionally been mocked for the number of games about physical or mental ailments that it's been used to produce. But these works exist in the context of a medium that historically hasn't made any space for explorations of weakness, hurt, or struggle. And far from being simple excursions in empathy tourism, many Twine games use interactivity to explore complex issues around embodiment and affect in wildly divergent ways.

Consider Depression Quest and Anhedonia, two games about the experience of depression. The former presents the player with a very systemic interface, one familiar to anyone with experience playing any kind of simulation game, in order to show the slow grind of mental illness, the way it keeps so many options just out of reach. Anhedonia, on the other hand, has links that behave in erratic and unpredictable ways, keeping the reader off balance. These two works use their interactive elements to tell very different stories about similar experiences of physical and mental distress.

Conversely, some works in Twine embrace the videogame logic of the power fantasy in order to subvert it. In Eva Problems's SABBAT, players invoke dark magic to transform themselves into badass demons. This might be the beginning of any typical videogame, except that from there the player goes on to have abortive sex with a witch, smoke magically enhanced weed, and instigate the overthrow of patriarchal capitalism. It's definitely a power fantasy, but an extremely unusual one, a fantasy of escape for those with antagonistic relationships toward their bodies—those who can feel something strange moving within them, waiting to be called into the world by just the right ritual. (To me it's totally a trans narrative too, but in a way that isn't necessarily obvious to non-trans audiences.)

Similarly, Aevee Bee's Removed uses imagery associated with conventional roleplaying games—hit points, turn-based combat, and so on—to tell a story about forms of power found in unusual places. In Sloane's Electro Primitive Girl, the trappings of the giant robot genre of manga become a vehicle to talk about femininity and strength. And in Winter Lake's Rat Chaos, the feeling of control and heroism produced by so many games is both harnessed and undermined in order to invoke a feeling of illusory power that ultimately must give way to uncertainty and the messiness of reality.

Finally, a number of Twine games aren't about dark magic or struggling with catastrophic psychological maladies or hooking up with the sexual partner of your dreams. They're about mundane experiences of daily life, the kinds of issues that have been widely considered "too boring" to be portrayed in mainstream games.

In Michael Brough's scarfmemory, the quiet English designer best known for his mechanically complex puzzle games expresses his grief over the loss of a treasured, self-knitted scarf. Even working in text, Brough's attention to the mechanics of play comes through to convey an everyday, personal experience of loss.

Similarly, Mary Hamilton's Detritus confronts us with the challenge of leaving and thus, leaving behind. Over a successive series of moves, the player has to decide what to keep and what to abandon. What objects do we invest with meaning? How do we pare down our lives again and again?

Finally, Jeremy Penner's There Ought to Be a Word explores the experience of dating during a separation from one's partner. As a piece about the complicated snarl of feelings that arise when a long-term relationship ends—even on the best of terms—it's a resonant, generous work about being a father that stands in stark contrast to mainstream games' recent clumsy, patriarchy-steeped attempts to put fathers in protagonist roles.

To be fair, mainstream videogames are more and more often attempting to deal with challenges other than violent ones, pains that aren't physical, goals that aren't acquisitive. But those projects are necessarily beholden to shareholders, making them subject to conservative convention and to the industry's ongoing desire to cater to young white men in the most reductive, shameful ways possible.

To see what's really exciting in videogames, we have to look to the fringes. From personal experiences of mental illness, to contracting with dark powers, to cruising at gay bars, to the adventures of space banditas in the far future and the experience of being a pregnant mermaid, the games in this book should be refreshing to anyone interested in the potential of interactive narrative but tired of games about grim antiheroes and Tolkien-obsessed fantasy settings.

I feel like it's important to note that I don't see this book as a "best of" Twine thus far, or as perfectly "representative" of the work being created with the tool. It felt simultaneously thrilling and overwhelming to build a list of games and then cull it down to a few dozen, and I tried my best to strike a balance between prolific writers and relative unknowns, between works that had touched me personally and those that had made an obvious impact on broader communities. And I tried to avoid too much of a temporal bias by including both older and more recent pieces. Unfortunately, of course, authors rudely continue to write while anthologies are being printed, and so nothing more recent than the fall of 2014 made it in.

Thus, instead of an exemplary or representative sample, I see this book as a dip into a river at a particular moment in time, gathering up some of the strange and unfamiliar things drifting past in hopes of inspiring others to do the same. If this book inspires further critical consideration of Twine, including more anthologies with their own editors who have their own editorial preferences, then I'll be overjoyed.

Choosing which works to include was hard enough. But then there's another question: how do you anthologize interactive fiction? Collecting the works on their own felt unsatisfying, and trying to literally reproduce them as physical choose-your-own-adventure books, while potentially an interesting commentary on the difference between those forms, seemed like a pointless exercise. So what could a book format add?

Jeanne Thornton suggested that we print playthroughs of each work, drawing on the tradition of annotated literature to produce a book that would be comprised of a series of conversations between games and players. Initially, we thought about printing this commentary in the margins, as annotations. But late in the process, we decided on printing single-column, with commentary following each passage. This format means that the book reads less as a linear collection of hypertext works with some added notes and more as a true series of dialogues between the works and their selected readers.

In choosing those readers for the book, I tried to pick people who I thought might have interesting things to say about a particular piece, who might have a personal connection to it, or who I thought might be fruitfully challenged by it. There's significant overlap between the list of authors who contributed games and those who contributed playthroughs, and that's by design. Twine communities are critically as well as creatively vibrant, with many authors generating insightful critique and analysis of each other's work, and although Twine works are certainly worthy of consideration by more traditional literary critics, we didn't want to set up a dynamic by which all the works in this book were up for judgment.

Still, in some cases I wanted to bring in readers who aren't involved in Twine communities themselves, but who I thought might have interesting perspectives. What would it be like to play through Eva Problems's SABBAT—a work that approaches themes of trans experience in a totally unexpected way—with Imogen Binnie, an traditional literary fiction author who writes trans stories like Nevada? What might Leigh Alexander, one of the most insightful games critics writing today, have to say about Christine Love's Even Cowgirls Bleed?

Admittedly, this was kind of an experiment—I wasn't entirely sure what to expect when I assigned readers their works. But what I got back astonished me. The playthroughs recorded in this book not only give Twine games the critical attention they deserve, but share broader insights about interactive fiction, digital games, and storytelling.

For example, in his reading of Fuck that Guy, Benji Bright's game about gay casual sex, Riley MacLeod draws out connections between gay men's tech-enabled hookups and the iterative, repeatable nature of interactive fiction. Just as interactive fiction allures with the promise of taking another path to see what might have been, apps like Scruff and Grindr continually present the promise of someone new — another chance, another possibility.

Other readers chose to dive deep into the inner workings of their subjects. As Naomi Clark plays Tom McHenry's Horse Master, she admits: "I have flayed this game to its bones, I have read the code." In doing so, she shows us the technical workings of the piece, providing a deeper understanding of the game than most players might typically glean. Nontechnical readers might wonder at the value of this kind of exercise, but given the ways in which all videogames are capable of hiding their rules from the player, this kind of deep reading of the code is as valuable as a technical analysis of the prose that makes up the game as the player experiences it, just as understanding the mechanics of syntax and rhythm gives us new ways to examine poetry.

And other readers still chart out the personal and artistic relationships between themselves and creators. Far from being signs of "corrupt" or insular design circles, as some conspiracy theorists would have it, these relations are critical to the development of any artistic community. In her reading of Aevee Bee's Removed, for example, Lydia Neon intertwines conversations about the messiness of memory and authorial intent with notes on her own relationship to the author. At one point, she actually texts Aevee, asking if one of the characters in the work is meant to be her. These kinds of relationships don't jeopardize some fabled notion of "critical distance"—they're evidence of generative links between authors that make up the broader communities this book is about.

To me, the conversational format of these "readings" suggests the feeling of sitting next to the player and listening to them talk about the work they're engaging with as they move through it. Some of these reflections are deeply personal, while others focus on the technical qualities of the work. (And given the diversity of approaches, some readings will inevitably appeal more to some readers than others.) In each case, though, the conversation between game and player feels greater than the sum of its parts.

4. the future

I'm beyond thrilled that this book has come together; I think it's well past due. But I don't want Videogames for Humans to be seen as the capstone of the "Twine revolution," a kind of historical record of some interesting work done in the early 2010s. Because really, in so many ways, this is still a beginning.

First, I hope this book kicks off more communication and crossover between fringe game design and literary communities. Above, I gave the example of the need for conversation between the parallel work being done by trans authors in Twine and in traditional fiction, but I think there's a more general need here too. Twine is marginalized within games circles for not fitting into the dominant shape of videogames—which means that Twine needs to build bridges to other creative communities. And literary and artistic circles, too, could benefit from taking a closer look at Twine and the exciting artists and authors who are finding their voice with it.

Second, I want to challenge the notion that the current state of Twine represents some kind of final achievement of diversity in digital games. Yes, it's fantastic that through Twine, we have more and more games by nontraditional game designers. But it would be a mistake to think that the relative success of Twine means that problems of power have been solved. For one, the status of queers, women, people of color, and people with disabilities in games is still tenuous. Few of these authors are accorded the respect, attention, or monetary success of their white male counterparts, even within alternative games communities, and publicly working in digital games is still an intensely precarious position for women, people of color, queers, and people with disabilities.

And while we should rightly celebrate the achievements of women and queers in this hostile space, I want to be real about the fact that we've been not nearly as proactive as we should about attending to issues of white supremacy. The people whose work the community holds up may be women—and often poor, gay, trans women, at that—but those female authors are still overwhelmingly white. There are people of color doing work in Twine, but they're systematically kept out of the spotlight. I've made an attempt to resist that dynamic in this collection, but it would be naive to believe that this book existed outside of the context of systemic racism.

To put it bluntly, this ongoing exclusion is bullshit, and if we're serious about building radical alternatives to mainstream videogames, to building more inclusive spaces, then we absolutely have to pay more attention to the ways that white supremacy manifests even in our supposedly more progressive communities. We need to constantly remind ourselves and others that so long as the women who are successful and visible as authors or designers are mostly white, we're not doing well enough.

Finally, I see this book as a step towards more human forms of digital play. I mean, I did call it "Videogames for Humans." Twine isn't the only or best route there, but it is an especially inviting one.

So what do more human forms of digital play look like?

They look like a move away from "the industry," from modes of production that rely on exploited labor and that perpetuate the technological fetishism of cutting edge, "hyperrealistic" graphics and "immersive" worlds in which we are meant to lose ourselves.

They look like games by and about more kinds of people, games not just about marginalized experiences, but created by and for people who historically haven't seen themselves in games and who have been denied access to them as a creative medium.

They look like games with a wider range of purposes, games that aren't about collecting or shooting or managing or accomplishing, but that are about communicating, interacting, resting, healing, and growing.

They look like experiences that use the unique features of videogames to connect people, rather than to isolate us from one another.

They look like games that are short, small, and generous with the player's time, that don't want to consume the player, but that invite them into playful engagement.

And they look like games that are positive escapes rather than negative ones, experiences that help us to imagine better worlds rather than simply providing temporary reprieve from the one we live in.

This book is one step toward all of that. Other steps are happening all the time, and I hope this anthology sparks many more anthologies in its wake.

This is a book about Twine. But let's not let it be the book, yeah?