Orrin Grey is a writer, editor, tabletop game designer, amateur film scholar, and monster expert whose stories of monsters, ghosts, and sometimes the ghosts of monsters have appeared in dozens of anthologies, including Ellen Datlow's Best Horror of the Year. He's the author of several spooky books, most recently How to See Ghosts & Other Figments.

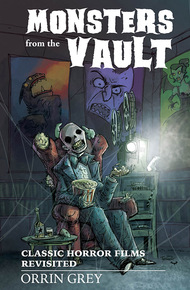

Author, skeleton, and monster expert Orrin Grey takes you on a journey of vintage horror cinema.

Welcome back to the Vault of Secrets, where acclaimed author, skeleton, and monster expert Orrin Grey will be disinterring a bunch of classic (or not-so-classic) vintage horror films for your delectation. Revisiting films from the earliest of the talkies (shot in two-strip Technicolor!) to Bert I. Gordon's 1976 "masterpiece" The Food of the Gods, this volume collects more than four years of Grey's popular Vault of Secrets column on vintage horror cinema, featuring everything from mad scientists to mole people, giant bugs to devil dolls, and more. Thrills, chills, and, of course, plenty of monsters await you within these pages. So dim the lights, grab some popcorn, and get ready for our feature presentation…

What better way to start this bundle than with Orrin Grey's great guide to movie monsters everywhere? Discover what lies hidden... in the vault! – Lavie Tidhar

"Orrin Grey provides a bite-sized introduction to vintage horror films. It's the perfect resources for those getting started in their classic film journey."

– bestselling author Silvia Moreno-Garcia"Orrin Grey's Monsters from the Vault is a delight. Grey takes the reader on a film-by-film journey trough some of the lesser-known horror films of the middle decades of the twentieth century, offering incisive and witty analysis of them along the way. Possessed of an apparently encyclopedic knowledge of these films, Grey points out connections among their directors, writers, actors, and production crews. The result is a book that can be enjoyed both for its discussions of individual films and for its overview of horror film during this period. Put this one on the shelf next to Danse Macabre and The Outer Limits Companion–even better, keep it on your desk, so it's close at hand."

– John Langan, author of The Fisherman.Welcome Back to the Vault of Secrets, the column on vintage horror cinema that I wrote for Innsmouth Free Press from 2011 through 2016. Before that, I wrote a column on international horror films starting in 2010, and a few installments from that have found their way into this volume, since they fit with the overall corpus of this collection.

I was born too late to be a true Monster Kid; by the time I was around, most of the old public TV horror hosts were gone, and the monster movies that were on Saturday mornings when I was young were mostly MST-worthy fare like Squirm and Godzilla vs. Megalon. Which is not to say that I didn't see plenty of monster movies, including those. I can remember watching C.H.U.D. and the Cronenberg remake of The Fly and Aliens in its network TV premier, which probably hit me about as hard as Star Wars did the people who were born a decade or so before. But I didn't see any of the classic horror films of yesteryear—the Universal monsters of the 30s and 40s, the Hammer horrors of the 50s and 60s—until after I had graduated from college.

That doesn't mean that those films were entirely absent from my formative years, though. My elementary school library boasted a nearly complete collection of the Crestwood House Monster books. Narrow books with bright orange and purple covers, filled with black-and-white stills from movies like Frankenstein, Dracula, Creature from the Black Lagoon, The Deadly Mantis, The Blob, and so on. To say that I read those books, even compulsively, is to undersell their importance. I consumed them, poring over those evocative images and imagining what the movies they went with must have been like. Those books did for me what I think the movies themselves did for earlier generations of Monster Kids, what Joe Lansdale beautifully summarized when he asked, "Isn't that the job of all great art, to kick open doors to light and shadow and let us view something that otherwise we might not see?"

I came to these movies late, but when I finally came, I fell in love with them, and I fell hard. I love movies from across almost every genre and period of time, and I hope that I never make the claim I see so many people make that movies from one era are inherently superior to another. But there's no other category of cinema that I love with the same totality of myself, the same abandon, with which I love the rickety old monster movies of the past. They come to me dressed in fake cobwebs and painted backdrops, and I fall into them every single time.

In general, I try not to give too much thought to the whys of it, in fear that I will somehow break the spell, but the thought is bound to cross my mind, and as close as I've ever come to giving a reason for it shows up in my story "The Seventh Picture," which is a love letter, as much as anything, to the films of Vincent Price and William Castle. There, I put my thesis in the mouth of one of my characters, who claims that, "Old movies just seem to capture weirdness better than new ones. Back when there were smaller crews, when things were made by hand. Weirdness slipped in that way, infiltrated, got in through the cracks and the crappy special effects. When you watch an old weird movie, you feel like you're watching something real, but also something not real, too. Like something from a dream, or an alternate universe. A universe where the sky's a painted backdrop, and fake trees grow up out of the fake ground."

It's my version of Lansdale's "doors to light and shadow," but it amounts to pretty much the same thing, in the end. There's a magic in old horror movies that modern ones can never recapture—which is okay, they don't need to, they have their own magic—and it will always hold a special place in my heart.

By the time I started writing the Vault of Secrets, I was still just beginning my journey into mystery the annals of vintage horror cinema. I saw my first Universal monster movie in college—it was Creature from the Black Lagoon—and a few others while I was working in a video store right after graduation. I didn't see any of the Hammer films until a few years later, when I bought an eight-movie DVD set featuring titles like Evil of Frankenstein, Curse of the Werewolf, and Paranoiac. While I know what my first Universal film was, I don't really have any clear recollections of watching it, but I can remember my first Hammer movie with perfect clarity. It was Night Creatures, and I was head over heels for it, in spite of it not featuring much night or any real creatures.

So writing the Vault of Secrets was, in many ways, an extension of my own explorations of the recesses of the field. As such, as I looked back over my columns to collect them here, there were a lot of things that made me cringe, both because of my ignorance of the genre and my ignorance of good writing. I like to think I've gotten a little less ignorant of both as I've gone along. As it is, there were lots of things in these columns that I wanted to change, but that's the nature of time, and, except for the minor alterations necessary to convert a recurring web column to book form, I resisted the urge to revise history, though I've added the occasional note of editorial hindsight here and there.

As you read through the columns collected here, you'll notice some possibly glaring omissions. You won't find much representation from the likes of Dracula or Frankenstein's monster, nor nearly as many movies as might be expected starring Vincent Price. In writing this column, I was operating under the assumption that the people reading it were probably already well familiar with most of those films, and I made it my goal, at least some of the time, to seek out more obscure fare. I'd like to pretend that this was purely for the edification of my audience, but it was in no small part for my own enjoyment, since by then I'd already seen most of the big classics, and I wanted to seek out films that were new to me.

So whether you're an aficionado of vintage horror cinema, or whether you're as new to the genre as I was a few years ago, welcome back to the Vault of Secrets, where we'll be unearthing some classic (and not so classic) horror films for your delectation. Dim the lights, grab your popcorn, and let's see what we can scare up…

Doctor X (1932)

Directed by: Michael Curtiz

Starring: Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray.

Doctor X is one of only a handful of surviving movies that were filmed in "two-strip Technicolor," in order to fulfill Warner Brothers' agreement with Technicolor. Going against the agreement, however, two versions of Doctor X were actually shot side-by-side, with only minor differences in takes. The Technicolor version was thought lost until recently, when it was restored by the UCLA Film Archive. That's the version that's in the Hollywood Legends of Horror Collection, and the one that I watched.

While Doctor X isn't the best film in the collection, it might well be my favorite of the bunch. The "two-strip" process gives the film a weird, lurid, pulpish color scheme that actually works brilliantly in complimenting its subject matter. I've heard people say that Doctor X is as close as you'll ever come to seeing a pulp horror magazine brought to life, and that may well be so.

The storyline concerns a series of brutal killings being perpetrated by the cannibalistic Moon Killer on the nights of the full moon, and the titular Doctor Xavier's attempts to ferret out the murderer by reenacting the killings in his creaky seaside mansion. There are all the usual trappings you could ever ask for, from hideously deformed stranglers to creepy butlers to mad science of every stripe, and Doctor X's house is filled with long hallways, dark shadows, and all the beakers and lightning machines that are the staples of the mad science genre. There's a great rogues gallery of suspects, as well as a bumbling newspaperman played by Lee Tracey, gamely ad-libbing many of his lines and scenes. The rest of the film's comic relief is supplied by the nervous maid, played by Leila Bennett, who plays basically the same character in Mark of the Vampire.

The sets are all wonderfully designed by Anton Grot, who did tons of movies, including The Mystery of the Wax Museum a year later. The Mystery of the Wax Museum is a spiritual successor to Doctor X, reteaming director Michael Curtiz, along with Fay Wray and Lionel Atwill, and is also filmed in "two-strip" Technicolor.

What really makes Doctor X great, though, is how thoroughly and unabashedly it manages to be everything pulpy all at once. There are mad scientists with big, ridiculous machines, gimmicky serial killers, brains in jars, a whodunit in a big dark house, a locked-room murder, a morgue scene, a skeleton closet, and everything else you could ever ask for. They even manage to work in some wax figures (which apparently melted under the hot lights of the Technicolor filming process and so actors were asked to play them by standing very still; you can actually see one of them move a little bit in a closeup). And since Doctor X is Pre-Code, it features references to cannibalism, rape and prostitution that would have been scrubbed from later films.