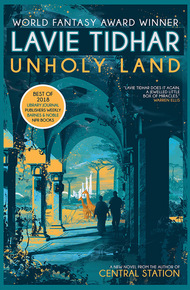

British Science Fiction, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Award winning author Lavie Tidhar (A Man Lies Dreaming, The Escapement, Unholy Land, Circumference of the World) is an acclaimed author of literature, science fiction, fantasy, graphic novels, and middle grade fiction. Tidhar received the Campbell, Seiun, Geffen, and Neukom Literary awards for the novel Central Station, which has been translated into more than ten languages. He is a book columnist for the Washington Post, and is the editor of the Best of World Science Fiction anthology series. Tidhar has lived in Israel, Vanuatu, Laos, and South Africa. He currently resides with his family in London.

Lior Tirosh is a semi-successful author of pulp fiction, an inadvertent time traveler, and an ongoing source of disappointment to his father.

Tirosh has returned to his homeland in East Africa. But Palestina—a Jewish state founded in the early 20th century—has grown dangerous. The government is building a vast border wall to keep out African refugees. Unrest in Ararat City is growing. And Tirosh's childhood friend, trying to deliver a warning, has turned up dead in his hotel room. A state security officer has identified Tirosh as a suspect in a string of murders, and a rogue agent is stalking Tirosh through transdimensional rifts—possible futures that can only be prevented by avoiding the mistakes of the past.

From the bestselling author of Central Station comes an extraordinary new novel recalling China Miéville and Michael Chabon, entertaining and subversive in equal measures.

It started years ago with a story called "Uganda", from HebrewPunk, about the ill-fated Zionist expedition to East Africa. Eventually the novel came, and it contains some of my favourite writing, I think. This book does a lot of different things, but I think it does them well. You can decide for yourselves, though! – Lavie Tidhar

"Lavie Tidhar does it again. A jewelled little box of miracles. Magnificent."

– Warren Ellis, author of Gun Machine"In the end, Unholy Land pulls off a remarkable trick: at one and the same time, it pulls the rug continually out from under your feet while still rooting you firmly in a sensuous world of tastes, sights and smells that never feels less than vividly real. For my money, it's the best thing that Tidhar has written so far, and that is very high praise indeed."

– Richard K. Morgan, author of Altered Carbon"Unholy Land is a wonder and a revelation—a work of science fiction capable of enthralling audiences across the multiverse."

– ForewordThe flight from Berlin was delayed. Tirosh dawdled by the gate. He was wrapped in a light coat. The airport's lines were cold and clean. The parquet floor gleamed. The glass walls let in a grey, diffuse light. Tirosh watched people go past.

People in airports were travellers taken out of time. Their clothes did not match their geography, their tan or lack of it did not correspond to the sunlight or the season. Their languages came from nowhere and went elsewhere, bringing with them always the scent of other, more real places, of brine and hot rain, seared fat, crushed flowers. The airport by contrast had the comforting artificiality of a well-constructed null-point, a sort of reassuring void. Earlier, going through security, Tirosh was lulled by the by-now familiar rhythm of checks and scans. He stood in the line gladly, shuffled forward slowly with the others, removed his shoes with a sort of glad compliance, took off his belt, emptied his pockets, turned off and on his phone.

The metal detector did not beep as he trod through it in his socks. Standing awkwardly by the conveyor belt, Tirosh reassembled those parts of himself that had been detached and scanned, put on his shoes, refilled his pockets, tied on his belt. For a time he wandered through the duty-free stores, amidst shelves filled with luxuries he had no interest in. In the bookshop he hesitated by the shelves densely packed with thrillers in which improbable men did improbable things. He did not find his own books there.

At the checkout counter he paused by the newspaper rack. The first page of several of the leading papers carried the latest atrocity from back home, but the pictures of the dead were all the same after a while, and he had grown immune to them. A few months earlier, reluctantly, he had participated in a topical news show on Arte where the interviewer began, straightaway, by accusing him of writing fantasy, and wasn't that an escape, to which he'd responded, somewhat defensively, that on the contrary, fantasy was the only way that allowed one to examine alternate realities, and wasn't that an important thing to do, politically, under the circumstances—but really he supposed it wasn't much of an argument. Mostly, Tirosh wrote a series of moderately successful detective novels, the sort that featured buxom girls and men in hats on the covers, the sort that used to sell in kiosks and petrol stations and pharmacies. He was not perhaps a hack, exactly: but after a promising start, he had abandoned his youthful ideals for the promise of a steady paycheque, and the writing of books which were delivered promptly and published cheaply and on time.

Purchasing nothing, he checked the departure board with a sudden sense of impatience (Isaac on his hands and knees crawling with a sort of dumbfounded delight as fast he could go; Isaac with his finger tracing circles on an empty phone socket, again and again) but saw that the flight was delayed. The people coming and going between flights seemed to him like revenants or ghosts, haunting the terminal corridors with the same sort of cancerous, restless energy he himself felt right then. He thought about Isaac. There was not a day gone past when he had not thought about his son.

He decided to keep moving, it was better that way. He found a café and ordered an overpriced orange juice and sat down to drink it. His telephone rang: his agent, calling from London.

"Where are you?" his agent demanded.

Tirosh said, "I'm still in Berlin. The flight keeps getting delayed."

"It will do you good to get away," his agent said. Her name was Elsa, and besides Tirosh she represented several more or less successful footballers and glamour models turned novelists; a former circus performer whose sex-filled, tell-all memoir stayed for ten straight weeks at the top of the best-seller lists; and a gaggle of desperate-looking crime and fantasy writers: their only fantasy was that they were successful, and their only crimes were committed against literature, as Elsa sometimes, uncharitably, told him. Sometimes Tirosh wondered what she said about him when he wasn't there.

"I don't know," he said. "I keep feeling it's a mistake, that I shouldn't go back. The place has probably changed beyond recognition by now."

"Nonsense," Elsa said. "You'll love it when you get there. All that sun and . . ." She cast about for something else to offer him. "I hear the street food is nice. Anyway it will do you good. How are you feeling?"

"I'm fine," he said, feeling irritated. "Why does everyone feel the need to mollycoddle me?"

He knew why, of course. He just didn't want to think it, and by thinking it to make it real.

He heard her silence on the line, then her breathing as she decided to change tack.

"Maybe you could do some articles while you're there," Elsa said. "I can speak to Der Spiegel, they're always looking for good coverage of the political situation there."

"I saw," he said, tiredly. "I'm not interested."

"Money's good," Elsa said. She always tried to get him to earn more. "Write a love story," she said one year. "Write something funny," she said a year later. "Everyone loves a comedy." Finally Tirosh, a little drunk, said, "Why don't I write a book about, I don't know, Adolf Hitler as a private detective or something, is that the sort of thing you mean?" and Elsa took a sip of her wine, frostily, and said, "Well if you're going to be like that, then forget it."

"It's the sort of place everyone has an opinion about," he said now, trying to justify himself and not really sure why. "But no one really cares."

"Do you still think of it as home?" Elsa said, perhaps a little sharply. Tirosh tried to formulate his thoughts. He glanced at the board. It said the flight was now, finally, preparing to board.

"I don't know. I mean it's me, it's a part of me, but I left, didn't I. It's in my language, it's in the way I think and see the world, but it's not to say I'm comfortable with it."

"You could do with a rest," Elsa said. "See some old friends, relax in the sunshine. Get drunk. Forget everything."

"Yes," he said. "Yes, that sounds like a good idea."

"Good, good," Elsa said. She sounded strangely relieved. Tirosh said, "I'd better go. I think the flight's finally boarding."

"Safe travels, then," Elsa said.

"I'll talk to you soon." He hung up and stood to leave with a sense of relief. People were congregating by the gate now, lining up in two rows. There weren't that many passengers. He noticed a woman, queuing in the line he hadn't chosen. It was only a glimpse, for him. He saw a woman with brown hair and pinned back delicate ears, which reminded him of his ex-wife, but with a sense of solidity about her, as though she were somehow more real than the artifice of the airport all about her. Perhaps she somehow sensed him watching, because she turned her head and frowned.

The passengers boarded the plane without incident. Tirosh settled back in his seat with a sigh of relief, or weariness. Images of his son kept flashing through his mind, and he blinked, rapidly, staring out of the window though it was fogged; it must have been raining. The woman with the brown hair sat nearer the front. He saw just the top of her head. The flight attendants went through the safety routine. The inside of the plane smelled of warm plastic, stale breath. There was a piece of gum stuck to the underside of the food tray. The engines thrummed alive. Tirosh watched small grey figures through the window, moving with a clear but unguessed-at purpose. He watched the runway move past, and tensed as the plane began to accelerate, then took to the air with a bump. The airport grew wider before growing smaller. For some moments there was the flash of fields, the density of a city, the silver snail trail of cars on a highway. Then they entered the clouds and the world turned white and grey, and fine strands of fog drifted past outside the window. Tirosh put his head back and closed his eyes.

"Hush, Isaac," he murmured. "Daddy is trying to sleep."

He thought he felt the touch of tiny hands, pulling on his hair; warm clear breath on his ear, and a delighted giggle, but it was nothing, just noise in the engines.

After a time he slept.

2.

When Tirosh woke up, his mind felt clearer than it had for a long time. He did not know how long they'd been flying. He felt curiously refreshed, renewed. He realised there were very few passengers on the flight, far fewer than he'd initially thought. His mind must have been playing games on him, earlier, but he had been tired, troubled by some vague memories he could no longer recall. He stretched and saw that the woman with the brown hair was there, sitting alone at the window next to two empty seats. When he peered out of the window, he saw the green slopes of the Cherangani Hills, growing blue towards the distance, with low-rising clouds settling over the higher peaks. Small villages sat amidst seas of green, and Tirosh saw the smoke of cooking fires undulate gently into the air.

"We will soon begin our descent into Ararat City," the pilot said. "Please fasten your seat belts."

A wash of memories came upon Tirosh then. How could he have ever forgotten Palestina? One does not forget one's homeland, no matter how long he may go away, how long he may dwell elsewhere, under a different sky, speaking a different tongue. The worries and the doubts of the past days fell away from him. Already the air in the cabin felt different, warmer and more humid. As the plane began to descend, Tirosh saw the hills peel away, and over a vast distance the Great Rift Valley opening and beyond it, like a smudge of pale blue, the sea.

Then, too, as the plane drew lower and lower still, Tirosh could see a fault in the land. A white towering wall cut through the sloping hills and fertile farmland. It snaked its way through fields and forests, separating settlements and villages, rising and falling with the land like an annotated series of discordant notes. Its whiteness stood glaring against the rich earth and its tones, startling against a sky already thickening with rain.

He looked and kept looking but could see no end to the wall in either direction, though it went round and out of his sight, continuing elsewhere. He began to discern new features on the ground, straight roads, slow peaceful cars like beetles, modern buildings gathering first in clumps and then in larger convocations until they became, at long last, one continuous wave as Ararat City rose in the view ahead.

He felt a pang of loss and a pang of joy at the sight. He wished Isaac were with him then, sitting in his lap, chattering nonsense words at the window, eyes round as he saw everything new. Ararat towered into the sky, with new, modern skyscrapers jutting out of the ground like grasping fingers. Glass and metal set off a contradiction against the dusty green beyond, and the white houses were like bold strokes of a painter's brush against concrete and asphalt and paved stone.

"Prepare for landing," the pilot said, tersely. He spoke Judean, and Tirosh realised he had missed the sound of his mother tongue. He searched for familiar landmarks, but the city had grown and changed in his absence, nothing he could have pointed out to Isaac were he sitting there, but then Isaac was away, back in Europe with his mother; he must have been; and he would see him again, soon.

The landing strip came up abruptly. The plane banked hard, then coasted, and the few passengers clapped. It was a strange custom, as though the landing were some remarkable achievement, a performance to be applauded, like the conclusion to a symphony performed by a full orchestra. But it was home; it was the done thing.

They disembarked shortly after. Ahead of Tirosh was the woman with brown hair; between them, carrying heavy luggage, was an elderly Orthodox man in the black garb and the felt hat of an Unterlander, accompanied by a wife and two children. The Unterlander turned and caught Tirosh's eye. He unexpectedly smiled, and gave Tirosh a wink. "A bi gezunt!" he said; which meant, "Don't worry so much, at least you still have your health."

Tirosh shrugged; and the man dismissed him with a "Psssht!" and a flick of the hand and turned back to his family.

As Tirosh stepped out of the plane, the humidity and heat engulfed him as though he had stepped from one world to the next. With them came the smell of Palestina: a mixture of tropical rain and car exhaust fumes, frangipani and jasmine and foods fried in oil. Tirosh took a deep breath, and when he expelled, it was the old breath of Europe he was expelling, and when he breathed again he felt renewed, much more himself. He was a Palestinian.

On the hot tarmac a bus idled impatiently, the driver smoking a cigarette by the doors. Tirosh climbed on board with the other passengers. He saw other planes parked out in the airfield, two British BOAC planes, a Uganda Aviation Twin Otter and an old Palestinian air force Spitfire, as well as a private jet, outside which a welcoming committee of sorts had formed, with suited dignitaries standing stiffly, only now and then turning their heads up to glance at the clouds. It was going to rain. The driver finished his cigarette and took the wheel. "Everyone here?" he shouted over his shoulder and, not waiting for a reply, drove them away at some speed. Tirosh watched the jet as the stairs lowered, and a line of Maasai men in ceremonial robes of animal hides emerged gravely, to be welcomed by the waiting dignitaries.

Then they were lost from sight as the bus came to the terminal building of the Nahum Wilbusch International Airport. Tirosh followed the others into the building and queued with his passport already held in his hand. It depicted the twin stylized lions of the old British Judea, holding between them a Star of David.

As a child, Tirosh still remembered hearing the lions in the distance, at dusk, on his father's farm. Sitting on the porch, watching the red sun set over the distant peaks of Mount Elgon, he'd hear them, calling with a sort of lonely pride across the distance.

It was then, with the cooling of the day, that the animals of the veld would come out to the watering holes, and a fragile sort of peace reigned, for a time, in the animal kingdom: lions would drink within sight of elephants and gazelles, intermingled with brazen birds, snakes, and crocodiles. Now, he thought, they must be all but hunted to extinction: farmers shot them, as the lions often attacked and killed the cattle.

"Tirosh?"

The border control officer was young and her hair was tied back severely. She wore the baobab-grey uniform of the Palestinian Defence Force.

"Yes?"

He tried not to look nervous. Even that simple word, y'a, came out haltingly, as though he had forgotten his own tongue and how to speak. He always felt awkward crossing borders, which were strange animate things to Tirosh, nebulous worm-like creatures which shifted between two states of existence, and also he feared officials. His grandfather, who had settled here as a young man fleeing Europe, had instilled in him a fear of officialdom which he had never quite lost.

The girl looked at his face, then at the passport, and she frowned. "You live outside?" she said.

There was something strange about the way she said it, as though it meant something more than he realised. He said, "Yes, in Berlin—" feeling like he was making excuses for himself, trying to justify a whole lot of things he couldn't say.

"What is the purpose of your visit?"

"My father," he said. "He is ill."

"Where does he live?"

She had the metallic delivery of an automaton, he thought.

"Fever Tree Farm," Tirosh said, feeling self-conscious. "In Elgon District."

The girl's eyes opened very slightly larger and she said, "That Tirosh?"

Tirosh shrugged. The girl looked at him again, doubt in her eyes, then handed him back his passport.

"Welcome to Palestina," she said.

He hurried away towards the barrier where more soldiers were standing. He saw the Maasai delegation enter the hall, accompanied by slightly wet-looking men in suits, who carried dark umbrellas.

A man in civilian clothing stood by the barrier. His receding hair was cut short and he had soft, sad eyes, or so an ex-girlfriend once told me.

There was no reason for Tirosh to know who I was; not then.

"Passport," I said. He looked at me, that sort of half-glance that doesn't really register: seeing a function, not the man.

"Tirosh?"

"Yes," he said, tiredly. Perhaps he didn't like his own name. There had been a fashion in the 1970s for modern, Hebrew-sounding names. His old name would have been something like Heisikovits.

"Is this your luggage?" I said. The soldiers brought it over, put it down on the examination table. They were good kids, not too bright, but eager. I gestured for them to put on the gloves and open the bag. Tirosh travelled light.

"Yes?"

"Could you empty your pockets, please?"

He complied, a man used to the indignities of travel.

"What is this about?" he said.

"Routine check," I said. "You understand."

"I'm not sure that I do."

I shrugged, apologetically. "Quarantine," I said. "We have to take extra precaution with people coming in from the outside. We can't afford any contamination."

"Do you mean biological?" he said. "I'm not bringing in any seeds or plants."

"It could be anything," I said. "Anything from the outside. Do you have a phone?"

"A phone?" he said. "What would I plug it into?"

I glanced at his eyes. They were clear and a little tired.

"Check everything," I said.

I watched his eyes as items were brought out, one by one. An analog watch, a toiletries bag, two folded shirts, a box of matches. I held the matchbox between thumb and forefinger, rattling it. I watched his eyes.

"Do you smoke?"

"No." A flash of confusion in his eyes. I nodded to the soldiers.

"Bag it."

"But what is this about?" he said.

"You have been outside for a long time?"

"I've been away, yes?"

I shrugged. "Sometimes you pick things up without even knowing it. Traces. It's best to be thorough. You understand."

He looked like he wanted to argue, but he didn't. I wanted to tell him about mimicry, about how organisms can disguise themselves visually in a foreign environment: like weeds pretending to be useful crops so as to avoid destruction.

I didn't, of course. To him I was just a petty official, then.

"Stop."

The soldier was little more than a boy, and no more aware of the procedure than Tirosh was. He hesitated with the case in his hand. "Sir?"

"My glasses case," Tirosh said.

I looked at him sharply. "You use glasses?"

"For reading," he said; unwillingly, I thought. I couldn't read his eyes.

"Are you sure you had them with you, when you boarded?"

"Excuse me? I don't understand your question."

I should have confiscated them. I don't know why I didn't. I don't think it really made a difference, in the end.

We confiscated a few items. A ring, a pack of cards. They could have been nothing. Tirosh was an unknown quantity. He'd been away a long time. He bore watching.

"You're free to go," I said, at last.

"Thanks," he said. "That's nice to know."

"Just doing my job, Mr. Tirosh."

"Curious sort of job," he said.

"You know Palestina," I said, and he almost smiled. "It's a curious sort of place."

I watched him walk away. He didn't look disoriented. He had this sort of gait that looked like he was always somewhat in a hurry but was making himself slow down. A sort of active nervousness. I hoped he wouldn't turn out to be trouble but, of course, he did.