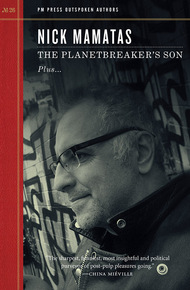

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Move Under Ground, I Am Providence and Sabbath. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Mystery Stories, Year's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, Tor.com, and dozens of other venues. Much of the last decade's short fiction was recently collected in The People's Republic of Everything.

Nick is also an editor and anthologist: he co-edited the Bram Stoker Award-winning Haunted Legends with Ellen Datlow, the Locus Award nominees The Future is Japanese and Hanzai Japan with Masumi Washington, and the hybrid fiction/cocktail title Mixed Up with Molly Tanzer. His short fiction, non-fiction, novels, and editorial work have variously been nominated for the Hugo, Shirley Jackson, Stoker, and World Fantasy Awards.

Upending and recombining familiar genres with fearless abandon, Nick Mamatas is known for his wicked satires in which Horror rides shotgun with SF as they power through Fantasy's rush-hour traffic. Lanes are crossed, speed limits exceeded, and minds often blown.

Our title piece, original to this volume, is something entirely new. Trust me. "The Planetbreaker's Son" is a starship novella in which interstellar emigrants maintain their stadium-sized vessel with dreams and play. On the fly. Think Pinocchio meets Ender's Game.

"Ring, Ring, Ring, Ring, Ring, Ring, Ring" is a cautionary tale about the perilous interface between ancient wizardry and modern ringtones. And it's for you. "The Term Paper Artist" is Nick's celebrated and hilarious how-to on embellishing the academic establishment with equal parts imitation and duct tape. Based on a true story of lies.

And Featuring: of course, our casually candid Outspoken Interview, in which Greek sailors, Japanese manga mavens, Doc Martens, Lovecraft, Grandma, and Kerouac mingle and mix. Care to dance?

It was Nick's idea to do this bundle, so blame him if you don't like it! I tend to think of Nick as the Holden Caulfield of science fiction, but his versatility is genuinely scary and here he turns his attention to SF, to all our benefit. – Lavie Tidhar

"One of the most inventive, fascinating, and distinctive voices in the field."

– Locus Magazine"Mamatas is a powerfully acerbic writer, both in fiction and online. His acid wit is infamous."

– Cory Doctorow"Mamatas at his best. Makes me laugh. Makes me drop things. Makes me read on. Makes me run for cover."

– Terry Bisson, author of Bears Discover Fire"Mamatas is such a great novelist that it's easy to forget he also writes superb short stories."

– LitReactor"Nick Mamatas is the gadfly that makes the horse buck whip-smart and no bullshit and with one hell of a bite."

– Brian Evenson, author of The Warren and A Collapse of Horses1.

The Planetbreaker's Son

It's funny, what survives, and what fades away, when all the world with its many histories is crammed into the tiniest of physical spac- es, then smeared across a virtual infinity.

Greek survived. Some of it did. Ρίχνω μαύρη πέτρα πίσω μου. "I'm throwing a black stone behind me." Done with a village, done with the port city to which you'd come to make your fortune, done with a life? Pick up a black stone and throw it over your shoulder as you leave, never to return. Take yourself and your stomach full of bitterness, but not a single regret, with you. Everything else you willingly leave behind, or have already lost.

When the planetbreaker's son was young, occasionally his mother would take him outside to see his father at work. It was always on a moonless night, and late. Mother would always wrap him in a blanket too, even during the dog days of summer.

"Well, here it goes," she always said after consulting her watch. It was easy to find the particular planet in the sky—everything is al- ways more obvious on a map—but soon enough Papa would throw a rock over his shoulder and the star would go up, flaring like a newly lit match, then fading to red and black.

Over in realspace, we're all just electrons stored in an object the size of a football field.

At home, where we all live, the sky is just a dome-shaped topo- logical map, screwed on tight over the flat world. The light from a world being broken reached the son's eyes moments after his father tossed the black rock over his shoulder. The planetbreaker would be home soon, or whenever he felt like it.

The planetbreaker didn't like to talk about work. He didn't like it when his son asked questions and didn't listen to the answers, or when he had to repeat himself, or much of anything. The planet- breaker didn't even like the practice of planetbreaking, though he was very good at it.

He did like his son, though he wasn't sure what to do with the boy. The relationship with his wife was over—when the planetbreak- er came home, he retired to the couch and caught up on the news. When the air was right, he ventured outside to look for black stones. He helped his son with his homework, watched realspace stories and played realspace games with him on the screens, though games were endlessly frustrating.

It wasn't that the planetbreaker had ever been RS but he had heard about those adventuresome days from his own father. Back when Earth was a thing under one's feet, covered in brown and sometimes green grass, with black and dusty cities, and well- spiced skies that could burn the hair from your nostrils after a hard day's work. RS games were different: for the kid, there were all sorts of little casual exercises in which he saved animals from the wild and got them safely stowed in pointy three-finned rockets.

For the kid to watch Daddy play, there were "mature" games: oh no, an RS meteoroid hit the object and someone has to grow some flesh, learn how to weld, and go outside! Or the object encounters another RS object, and an exchange of personality emulations leads to a political crisis, or an "alien invasion," or a quasi-religious telos— the return to RS, on a new blue Earth, where everyone receives another chance to get it right. Games were dumb, but soothing. Simple decisions, bright colors, and the planetbreaker's son would bark childish advice and smile at his father when the planetbreaker did well.

The planetbreaker and his wife—Zeus and Hera! They fought the way dogs do, all mouth. Father smoldered and snapped, Mother sniped and demeaned him, then Father erupted and Mother squawked in fear and indignation. The walls nearly derezzed, the floor quaked. When Papa rolled his eyes and growled through clenched teeth, the very sky went blank. The little planetbreaker's son loved his mother more than his father, which is right and natu- ral. But he tried, the boy, to amuse his father with jokes about farts and cartoon characters and dancing around. "Are you happy now, Papa?" he asked, often.

"I'm always happy," the planetbreaker said, always, his voice that of a dead man.

The planetbreaker's wife had a much more interesting and vital job than that of her husband. She worked in RS, sliding her being into any number of tentacular waldos to scramble through conduits and down tubes, maintaining and improving the ship. Twice she even engaged in EVA to make repairs to the skin of the football field in which we all live. Not in the flesh, of course, but in a little wheeled repair vehicle that rides along the exterior of the ship on tracks criss- crossing the surface. RS work is nothing like RS fiction—there's no excitement. Should we put a metaphor here? Does it make sense to address the recipient of this message with "RS work is like taping off a room before painting it" or "RS work is the opposite of a spread- sheet in a twenty-first-century office; real things are moved around to represent the virtual." After all, every possible recipient of the message already knows all about RS, our football-field-sized space- craft/ice floe/coffin, and about the post-Singularity virtual habitus (many—the plural of habitus is habitus) in which we experience our disembodied existences.

Ah, but we already said football field at the start! Got us there. Not only is every possible recipient of this message already an inhab- itant of a post-Singularity virtual habitus, but all the actual recipi- ents of the message are well situated within a habitus where "football field" and "spreadsheet" make sense.

So it's easy to imagine—a woman, Caucasian mostly, with straw- colored hair piled on her head and kept in place with bobby pins, takes a seat on a wooden chair and sips tea from a mug. Somewhere in RS, a small machine the size of a waffle iron scuttles from point A to point B, laying atom-thick wiring across the skin of the ship. She goes out with her friends to see a movie, or swim in a pool, or just split a couple bottles of wine, and the magnetic field that scoops up hydrogen from the interstellar medium to fire it out a bank of ramjets astern adjusts ever so slightly. She goes to her job, writing marketing copy for medical devices that she has never seen and that nobody will ever need again, and server loads are calibrated.

The planetbreaker's wife is in a good social position—she knows that she works with RS, that the details of her quotidian life are in fact vitally important to keeping a million tiny stars twinkling in the sky and a spacecraft sucking and shitting its way through space. Not like her husband, who is blind to these things, who sits in his chair and frowns at his son until some inexplicable urge strikes him to visit another world. Not like her son, who thinks RS is all laser swords and telekinetic powers that sandy-haired boys just like him will one day manifest if they're good enough and practice with splayed fin- gers and pshew-pshew noises.

The planetbreaker's wife wants a second child, but bearing one would cause immense structural damage to the ship. It's the wanting of the second child that keeps the engines grinding forward in RS.

The planetbreaker has always wanted three kids, ever since he himself was a child, though of course he was never actually a child, just some lines of code emulating the desire to become a man and sire three children—boy/girl/TBD. He only has the one boy. One day, when his wife was distracted with her new hobby of zesta-punta and the entirely artificial subsentient lover she had met on the prac- tice cancha, the planetbreaker found his son on the carpet, his thin arms holding open over his head a paperback copy of Dubliners.

"Are you really reading that?" the planetbreaker asked his son. "You're seven years old."

"I want to know what it's like to be nine, like the kid in 'Araby.'"

"You should read a Greek story about a nine-year-old, not an Irish one," the planetbreaker said.

"Tell me one," his son said.

"Come with me. We need to find some rocks."