Alexander Jablokov writes literate science fiction with just enough pulp. He likes a good sentence, and an unexpected end to a paragraph. His interests include architecture, city life, Byzantine political scheming, and quirky characters. He is also a Martian habitability skeptic, and would appreciate it if you kept that last fact just between you two.

Alexander Jablokov writes literate science fiction with just enough pulp. He likes a good sentence, and an unexpected end to a paragraph. His interests include architecture, city life, Byzantine political scheming, and quirky characters. He is also a Martian habitability skeptic, and would appreciate it if you kept that last fact just between you two.

Alexander Jablokov writes literate science fiction with just enough pulp. He likes a good sentence, and an unexpected end to a paragraph. His interests include architecture, city life, Byzantine political scheming, and quirky characters. He is also a Martian habitability skeptic, and would appreciate it if you kept that last fact just between you two.

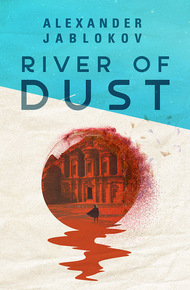

A revolution is brewing on Mars, one that will split the two sons of the politically prominent Passman family. As Hektor supports his father in an attempt to prevent the collapse of order, Breyten, the younger brother, joins a fanatical cult whose leader has his own mysterious purposes.

The story moves from the dense underground cities, with their orgiastic festivals, riots, and ceremonial executions to a final confrontation on the uninhabitable Martian surface.

River of Dust by Alexander Jablokov is a Cain and Abel story transposed to a Mars where—unlike the happy outcome in Kim Stanley Robinson's Red/Green/ Blue Mars trilogy—surface terraforming failed, forcing the human settlers to create an elaborate underground tunnel system and an equally labyrinthine culture. River of Dust (as well as its sibling, Carve the Sky) unfolds in a vividly imagined neo-Byzantine universe where the planets, moons and asteroids of our solar system have been inhabited and shaped by branches of humanity. Their diverging physiologies, cultures, needs and resources create potent inter- and intra-planetary power struggles that exert their gravitic pull even on ordinary lives, splitting families and friendships. – Athena Andreadis

"Jablokov paints a world of treachery, political intrigue, obsessive men seeking to impose their will on the world around them, and others driven by grief or belief or the lust for power."

– Science Fiction Chronicle"Jablokov tells a tale of guilt and sibling rivalry set in a convincing world of a Mars in decline, hundreds of years in our future."

– SF Reviews"The best part of River of Dust is the vividly imagined texture of the society. Mars has its own myths and histories, stories of martyrs and fools that the people of the day use as props in their own continuing stories. The social rituals of Martian society are also richly tapestried, and Jablokov makes some interesting commentary on what it might be like to live in a stressful environment that can kill you at the slightest mistake."

– Challenging DestinyPrologue

"There," Brenda Marr whispered, then examined the sheer cliff of the mesa again to make sure she wasn't deluding herself. The dark oval of the air lock high above her, just a bit of human regularity against Martian rock, marked her destination, the Pure Land School.

She had been five days hiking from the nearest train station into the fretted terrain of Nilosyrtis. The recent solstice dust storms had obscured any rough trails among the crumbled, looming mesas. She had moved slowly through the sinuous, dust-choked channels, remembering her long-ago sojourn here, and the landmarks that had once been so distinctive. Nights she had spent in a fragile air cocoon barely larger than her own body, checking and rechecking her air supply and feeling the growing dryness in her throat. Her air would have run out before the rise of Phobos tonight, but she didn't think about that now. She had made it. She was back. She hoped that this was where she was meant to go.

Sunset glared above the long cliff of Shadrach's Mesa to the west. A flicker of movement caught her eye and she looked up past the tiny dot of the air lock. A group of figures stood on a spire cleaved from the edge of Pure Land Mesa and stared off at the setting sun. Some held their hands out to the sun, though it gave no heat. They wore school robes, and their air masks were completely reflective, turning their faces into roiled orange flares. It had been a long effort to climb that high just to watch the sun set, and they would have to descend in darkness and feel slippery rime ice condense in already-treacherous finger and toe holds. Brenda remembered the joy of it. A few cairns in the piled talus at the base of the mesa marked the graves of those whose joy had grown too great.

Above the talus, stairs chopped into the face of the cliff zig-zagged up, taking advantage of its irregularities. They had probably been cut when Rudolf Hounslow moved out here to his self-imposed exile, a decade before, but there were those who said they were much, much older. Just by appearance, given the absence of weathering on the Martian surface and the human race's eyeblink habitation on the planet, the stairs could have been there for three hundred years or been carved the day before yesterday. Brenda knelt, pulled off her gauntlet, and felt the sharp stone through the inner glove of her skintite. Her left pinkie finger throbbed its emergency message: her air was running out. Dammit, she knew that already.

She started up. Now that she was almost at her destination, tiredness filled her bones. She hadn't felt tired since...when? Since stumbling out onto the rim of Coprates Chasma to open up her tracheal valves and foam blood out into the indifferent Martian air. She remembered herself standing and looking out over the canyon to the sharp opposite wall one-hundred-fifty kilometers away. A single bright light halfway up that seven-kilometer-high wall opposite had marked some still-functioning industrial operation. It flared there in the darkness, leaving a network of crisp shadows across the cliff.

That steady, indifferent light saved her life. She dropped her hands from her throat valves and stared across the vast width of Coprates in sudden fury. Her last, pathetic attempt at normal existence had just been peremptorily ended, and those bastards worked all night? She imagined that she could see the endless stream of rock spoil spilling out and cascading to the canyon bottom, a glittering sight at sunrise. Her side of Coprates was as dark and silent as it had been before human beings came to Mars.

When she stepped into the elevator for the long ride down to the now-silent quarters of Iqbal-in-Coprates Mining, her anger was vague, nothing more than a desire to hurt those who still had work left to define them. By the time she got off at the deserted dormitory, now inhabited only by a few last laggard dispossessed Iqbal employees, she knew where she had to go: the Pure Land School. Her memories of the place suddenly seemed much more significant than her actual experience there had been.

She had searched amid the foul dunes of clothing left after the worker exodus and extracted items that could be useful to her. A few scratched and dented personal weapons had been abandoned, as had a container of brutally overspiced emergency rations. Brenda had taken one last look across the ranks of sleeping alcoves, carefully not noting which one had been hers, then turned and left. Once she stepped through the security door, she was committed. It was programmed not to let any former employee back in, acting as a social Maxwell's Demon.

She had been a good week traveling northeast from Coprates to the crumbled mesas and deep channels of Nilosyrtis. Brenda had sat in a comer of a common car, tumbled promiscuously with all those other travelers too poor or too indifferent to comfort to obtain a private compartment, as she switched from magtrack to magtrack, working her way along the edge of the Vastitas Borealis, the great plain of dunes that stretched north to the polar cap. The weight of her dagger heavy on the back of her neck, she had sat on her survival pack waiting tensely for some affront, some attempted assault, her hat pulled down low over her mass of red-brown hair, but her neck open so that she could reach her weapon easily. No one had paid the slightest attention to her. Everyone seemed sunk deep in some private concern. The normally ebullient social life of the common cars had been subdued. It seemed that it was not only the former employees of Iqbal-in-Coprates who had worries. She felt a vague disappointment that no one had made a move at her. A response to that would have been easy. She would have known instantly what to do, and the flashing rush of anger would have taken care of her future. Instead, after an uneventful journey, she had gotten off at Garmashtown, on the edge of Utopia Planita, slung her pack, and started her long walk toward something she wanted to remember.

She stopped now and looked at the oval of the air-lock door. It had slid back, expecting her. She stepped in. She had time for one last glimpse of the landscape over which she had just so arduously traveled, the indigo bars of the mesas disappearing into encompassing darkness; then the door slid shut and the air lock cycled. The inside door opened and she found herself in the rock-cut antechamber she remembered.

Brenda disconnected her tracheal valves, peeled off her air mask, and sucked air gently between her lips, surprised at the sweetness of its taste. If the Pure Land School had been a few kilometers farther, she would have died. She listened to her breathing. It sounded calm to her. The Pure Land School was right here. She was breathing its air. Any other possibility was foolish.

"Brenda Marr," the fair-haired novice on duty said, with an air of having expected her. Bemused, Brenda examined the snarling cat face on her mask, the standard design of Iqbal-in-Coprates Mining, then tossed it into a disposal-sorting bin. She would be given another. The life marked by that mask was now over.

Brenda had once been a novice and worked this duty. She too had memorized the names of all those who had left before her so that she could greet them appropriately when they returned. The novice's eager face implied that she should be fooled, and find his knowledge in some way miraculous.

He helped her strip off her pack, her dusty exterior clothing, and her skintite, hanging everything on a rack where it could be taken away by someone else and cleaned. He was smaller and slenderer than she was, and when she finally stood before him completely naked he looked a little surprised, as if he had not expected the result. Her long red-brown hair was tangled and matted from being shoved under her exterior hood. She winced as she felt the tangled knots. She'd lost weight in the past two weeks of frantic travel, but she was still thick and queenly. Her heavy breasts hung ripely down on her rib cage. Her belly was round. Five days straight in a skintite had given her a strong, sour odor.

"Do you—" Her voice came out a croak. She cleared her throat. It had been weeks since she had spoken. In that time she had come close to dying twice. She was surprised she could talk at all. "Give me a robe. I should see him now."

Rudolf Hounslow, Master of the Pure Land School, always talked to returnees as soon as possible. He didn't want them cleaned up and rested. By that point, they had lost most of what made them important. He regarded them as newborn infants who might still retain some knowledge of their previous life. Aching joints and dried sweat were signs of their closeness to their memory. She remembered his intent, somehow-never-satisfied curiosity. Perhaps she could show him something that would satisfy him.

Silently, the novice, whose name was Marder, held out a tall ceramic container of water. She drank it slowly, but without stopping, until it was empty.

He was still staring at her. His blue eyes were large in his face. She stretched, feeling her ribs move under her skin. The attention, sexual or not, infuriated her. It smacked too closely of the life she had led in the Iqbal dormitories for four years. She tensed her arm to push him away—he was light, it wouldn't have been hard—but then she relaxed. That attention, intent though it was, would keep him from noticing other, more important things. Like the knife she still had strapped to the back of her neck.

She met his gaze. He stood easily, and she suddenly suspected attacking him would not have been as easy as it had first appeared. He held out a robe. "Here. Let's find him."

The Pure Land School had a sort of rectilinear logic rare on Mars. Even rows of cubicles, straight balconies opening out onto the cubical central space, light sources like beads on a taut wire: this center of Martian spirit looked like nowhere on Mars since the first era of technical settlement, during the twenty-first century. Brenda looked at the familiar hallways, hoping they would somehow be illuminated and their hidden message made clear, but they were still nothing but elemental stone.

Rudolf Hounslow squatted against a featureless wall like a corridor shoe mender. He had never had any place within the Pure Land School that he defined as exclusively his own. As free from confining definition as any corridor nomad, he made his bed where he was, on the smoothed rock, and ate with chopsticks from a bowl he held in his hands.

Now he stared thoughtfully at the floor, crossed arms resting on his knees. His dark silk robe, no different from any student's, fell around him and concealed his legs, leaving his blocky head balanced like a boulder on an outcrop. The novice, Marder, floated away along the balcony, his fine gold hair a halo around his head.

Hounslow turned his head slowly to look at her. She almost stepped back from the intensity of his gaze. There was too much need in it. There was something he wanted from her, and she was suddenly afraid she would be unable to give it to him.

"When did you realize you should come back?" he said.

"I—" She wanted to tell him all the details, her life in the workers' dormitories, her succession of indifferent lovers, the demands of her work, the humiliation of losing a job without warning or explanation. "When I found myself standing on the rim of Coprates Chasma opening my throat valves to Mars."

"Now," he said. "Now you understand. Thoughts rot in the head if they are not turned into action."

She stared at him. Four years ago, she had heard him use the same words, here in this same place. And still he sat here, calm, measured, creating the philosophy that would transform Mars.

Hounslow, after a troubled early life, had made his fortune growing silk in the caves of Charitum. His followers now wore robes made out of that silk—he could still get it at a discount. He had also had success with a couple of romantic-adventure novels, under a pen name. Brenda had read them as a girl and enjoyed them, and now wondered if they had held some concealed message that had finally brought her to the Pure Land School. Then, for his own private reasons, Hounslow had left his successful place in Martian society and started his philosophical school out here in Nilosyrtis, far from any settlement.

Here he preached the necessity for action against the increasing corruption of the Martian political system. She had heard him denounce a session of the Chamber of Delegates bill by bill, citing the corrupt compromises that made up each one. Brenda still remembered that particular talk with exhilaration. His words had been as real as blows. Hounslow had become so taken with his own impassioned rhetoric that he had attacked the wall of the lecture room with a wooden sword he had carved himself. He had been proud of its elegant balance, the result of much careful work, but when he was done, it was nothing but splinters, and his hands were bleeding. He turned back to the class, which had not uttered a sound, and continued with his detailed denunciation of routine Chamber water bills, letting the blood fall in drops from the tips of his fingers.

But Hounslow was still here. The School was silent in the early evening. Why had she thought the Truth was here? This serene place had nothing to do with her own life. She remembered the corridors of Scamander, choked with anxious crowds smelling of frying peppers, arrack, and sweat. She remembered the society of the mining dormitories, and the frenzy of work.

In the days after the closing of the Coprates mines, she had found herself unable to sleep, missing the endless thrum of the slurry pipes. The pipes could have been designed and built to be silent all along, of course, but a physical connection to the work was always necessary. Nothing on Mars worked as smoothly as it could have in theory, so that human beings could feel themselves defined against the resistance of the physical.

But Hounslow had not moved. He still squatted in his corridor.

Brenda's skin flushed, and she trembled.

Hounslow nodded at her, seeing the revelation, misinterpreting it.

"Teach and teach and teach," he said. "The lesson doesn't reach its goal. Release, disregard, and illumination comes. A phrase repeated a thousand times until it isn't anything but a gabble of syllables suddenly pierces the heart. You are ready to go on."

She reached up and felt the back of her neck. It was a habit among the prostitutes of Scamander to carry a knife concealed in the thick hair at the nape of the neck, for self-defense. Brendah ad recently seen society ladies aping it, as idle fashion, leaving a stiletto point protruding at an angle from their hair, where it could draw blood from the hand of an incautious lover. That missed the whole point. You should cut only on purpose, and then cut deep.

This blade, one she had retrieved from the discards before leaving Iqbal, was a little too heavy for the purpose. Every time she turned her head it clouted her behind the ear. The most drunken client would have felt it right away. But it had been years since she'd descended to men like that. Her last client had been as high as they came, and she'd quit after him. It would have made no sense to take such a knife in to him. His bodyguards would have caught it immediately. Her fingertips slid across the friction-taped handle of the dagger.

"Not all actions are equal," Hounslow said. He rocked forward slightly on his feet, moving his back from the wall, but didn't try to stand up. His tone was mild. He looked up at her as she tensed to pull out the knife. His eyes were pale disks in the half-light of the hallway.

She froze. He had shifted position only fractionally, but it had changed everything. He was a compact mass, ready to roll in any direction or spring up at her. She, meanwhile, would have to stab downward, like a hysterical husband in a street play, and leave herself exposed for a counterstroke. Any attempt to shift to a more efficient attack position, and he would be on her. He was combat-trained. She'd seen him spar.

She should do it anyway. At least it would remove them both from this stupid realm of words. She might still be able to wound him and give him a lesson to feel late at night when he couldn't sleep.

"Who sent you?" She could see how excited he was at the thought of assassination. His skin had flushed, just like hers. "Was it Passman?"

She had no idea what he was talking about. "You sent me." Her voice was loud in the corridor, so she dropped it to a whisper. "Action. That's what you said."

It no longer made any sense at all. She hadn't come here to kill Rudolf Hounslow. Nothing like that had been on her mind.

She had come to hear him and to feel his certainties.

"You're from the Vigil," he said. "A special operations unit—"

'No." She reached back up behind her head, ripped the knife out. The tom hair brought tears to her eyes. She flipped the knife once, almost catching it by the blade by accident, then threw it to the floor. It skittered across the stone and came to rest against his foot.

"Check whatever you want," she said. "My life is completely out in the open. I've spent the last four years digging ore out of the rim of Coprates. That's it. You know who I am. I'm yours. You are the only person I'm from. So what do you want to do with me?"

His bodyguards could be on her in a second. He always pretended he didn't have any, and perhaps he even believed it himself. They selected themselves and came to crouch next to him. And he let them, because he liked the sound of their purring. Marder was still somewhere near, she was sure of it. She'd noticed the cultivated calluses on his hands, marks of intensive hand-to-hand combat training. And he'd seen the knife; of course he had. He'd let her through as some sort of test. Life at the Pure Land School was full of tests.

She would be "invited to meditate": taken up to the flat top of Pure Land Mesa to view the vast broken lands of Nilosyrtis Mensae, there to suffocate. That was always the fate of those suspected of being Vigil agents. Everyone at the Pure Land School knew that the Martian political police force was desperate to break open Hounslow's organization, though no one had ever bothered to confirm whether the dead students had actually been acting under Vigil instructions. They left that sort of tedious administrivia to the servants of the corrupt political class. The whole school always turned out for the funeral, to mourn another brave fighter for the purity of Mars.

Sometimes, of course, the funeral was for someone who had really died in pursuit of duty. Such a ceremony was, in outward appearance, no different from one for someone considered a traitor. If she died here, Brenda would receive such a funeral ceremony too.

"You should stay here," Hounslow said. "You should learn more, try to understand...."

"No."

He looked up at her, expecting some further argument or justification. He was hungry for words. But she didn't give him any. The silence was long. "All right. I want you to do something for me, Brenda Marr."

Marr stared at him and waited.

"I knew a man, years ago." Hounslow picked the knife up and began to scratch its tip against the stone. "His name is Lon Passman. Right now he is Justice of Tharsis."

Despite herself, Brenda felt a response. "Justice of Tharsis" was a high title, being one of the five Judicial Lords who represented the apogee of justice on Mars. Despite his withdrawal from it, Hounslow enjoyed showing how high his contacts in Martian society had once been. The entirely voluntary nature of that withdrawal always had to be emphasized.

He looked up at Brenda. "We had a bond then. That bond was broken. Now he has presumed on it, as if it still exists, to contact me, plead with me." His brow furrowed in anger. Brenda's attempt to kill him had not called up this much emotion. "I need to send him a message. I need him, and everyone, to understand what is coming. Do you understand?"

"You want me to take the Justice of Tharsis a message." Brenda's voice was dull. Hounslow had called her back from the edge of destruction yet again in order to use her for some stupid errand.

"Not just a message!" He extended himself slowly and finally stood. At the last moment he shook a little from the lack of blood circulation in his knees, and steadied himself against the wall with a hand. Brenda was taller than he was. "It's the first shot in the war. And I want you to fire it. Will you do it?"

In the inspirational plays she'd seen as a girl, this was how it always was. A powerful older figure, normal channels of power disrupted, turns to the previously ignored child and gives the child a mission, a mission only the child can accomplish. Carry a message, let the lord know I love him, tell the commander where the Technic invasion force is concealed, recite the rhyme that contains the secret to the buried treasure. Be quick, clever, and invisible. You will get your reward.

Brenda was tired of being invisible. Carrying a message, no matter how important, was not an action.

She would have to find a way to turn it into action. That would be her reward.

"I'll do it," she said.