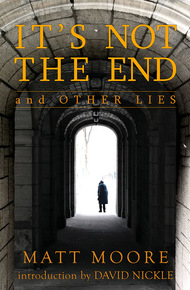

Matt Moore is an Aurora Award-winning author, poet and columnist. His work has appeared in On Spec, The Drabblecast, the Aurora Award winning anthology The Sum of Us (where his story "Good-Bye Is That Time Between Now and Forever" made the Sunburst Award's long list), The Ottawa Citizen, Leading Edge, Polar Borealis and more. His short story collection It's Not the End and Other Lies, his first full-length work, was first published in 2018, which contains two Aurora Award finalists and another story on the Sunburst Award long list. He's also a Contributing Editor for AE: The Canadian Science Fiction Review, and a frequent panelist, presenter and instructor. Raised in small town New England, a place rich with legends and ghost stories, he now lives in Ottawa, Ontario.

It's not the end of the world, just yours

Tales of the bizarre, the terrifying, the all-too-near future. Twenty-one stories of "personal apocalypses"… because someone's world is always coming to an end.

Only able to recall the memories of others, a ghost tries to solve the mystery of his death. The zombie apocalypse is the gateway to a higher human consciousness. An amusement park of the future might turn you into the attraction. Three teens must play an impossible game where each choice could make them a victim, or a killer. A mercenary races to save humanity by killing its saviour. After the sky falls, can anyone still hope?

Includes the Aurora Award finalists "Touch the Sky, They Say" and "Delta Pi", the Sunburst longlisted story "Only at the End Do You See What Follows", and an introduction by David Nickle (Eutopia, 'Geisters, Monstrous Affections).

One of the good things that came out of ChiZine for me personally was meeting and becoming friends with Matt Moore and his lovely wife Kate. They're Ottawa-based, and I'm in Toronto, so our interactions have mostly been restricted to conventions and the ubiquitous room parties, but those interactions have always been immensely enjoyable. I had the honor to give feedback on an early draft of "Silverman's Game," one of the stories in It's Not the End and Other Lies, and it's a thrill to see it in Matt's first collection and to include these stories in this bundle. Matt is one of the "newer" writers in this bundle, but his talent stands equal with the rest of these authors. His short stories are little gems, and like gems, they can be sharp, hard, and beautiful—cutting even as they glow. – Douglas Smith

"Subtle power, intelligence, and humanity are the hallmarks of Moore's work. These stories are apt to stick in your mind like quills."

– Nick Cutter, author of Little Heaven, The Acolyte, and The Troop"Brilliant. End after end after end, it's tightly written, thought-provoking and ultimately heart breaking."

– John F.D. Taff, author of Little Black Spots, The End in All Beginnings, and The Bell Witch"Matt Moore writes a line that resonates and reverberates with the reader long after the eye has moved on. Moore's stories are subtle, unassuming, coaxing you in with the banalities of real life—even if the stories themselves are fantastical—only to claw into your heart and mind. Moore's ideas are plainly in the realm of the supernatural and the monstrous, but his heart is in the humanity of the people that populate his stories; you'll recognize people you know in Moore's work, relate to the actions his characters take. Matt Moore's greatest strength as a writer is conveying the humanity and the possible to the monstrous and the impossible."

– Paul Michael Anderson, author of Standalone and Bones are Made to be Broken"Touch the Sky, They Say"

Four steps up onto the observation platform and the sky is barely a foot above my head. Featureless, gray—a morning headache after a bad night's sleep. Same as it looks from the street, 41 floors down.

Up here, the wind is July-hot and attic-dry, switching directions, rippling our clothes. The group is a mix. A couple of business types on lunch. There's a middle-aged guy in black jeans and a sleeveless Harley Davidson shirt. A teenager with spiked hair despite his school blazer and tie.

The last one up is a girl in her twenties with peroxide-blonde hair and a Ramones T-shirt. She doesn't hesitate—fingertips stroke the sky. I see my own uncertainty mirrored in her expression. Once in a while, the stories go, someone collapses to the planks of the platform, sobbing.

Not her.

She lowers her hand and descends the wooden steps to the elevator, heavy boots clopping all the way. A pudgy man with crescents of sweat in the armpits of his suit presses his palm against the sky for an instant, then follows the blonde.

There's six of us left, trying not to make it too obvious we're all waiting to see who will go next. The Harley shirt turns and leans against the wooden railing. We're at the highest point in the city; you can see for kilometers. See straight across to where the sky cuts through the CN Tower and the truncated columns we used to call skyscrapers. Maybe he's just here for the view. I join him at the railing and look south. The lake's calm today, reflecting the sky's perpetual flat, gray light. I jam my hands in my pockets, fingering the folded-up rejection letters.

Far below, a car horn sounds, echoes, fades. The familiar quiet resumes. Since the sky fell, we're all so polite. A quick toot of the horn used for caution, not a weapon, not a complaint. Years ago, waiting for one tutor or another in a music room lit pure-gold by the afternoon sun, I used to focus on the constant blare of rush hour, picking out horns not tuned to F major.

The kid with the spiky hair appears next to me, hands on the railing. He leans far over and, for a second, I think he's going to jump. But he rocks back, curls his hands into fists and drums them on the railing. A complex beat in 3/4 time.

The man in the Harley shirt straightens up and shoots a fist against the sky. His knuckles crack and he grimaces. The stillness broken, two others reach up. A moment later they're down the stairs.

The kid watches them go, then moves to the other side of the platform.

Wiping sweat from my forehead, I check the clock above the elevator doors. I've been here for eleven of the fifteen minutes my ticket allows.

The career woman in her expensive pantsuit and hairdo raises her hand, eyes shut. On contact, she shudders and lets out a small sob. But that's it and she's gone, high heels clicking down the steps.

Just me and the kid, now. I wonder what his story is. Maybe he wonders about mine. We probably both wonder if it's true what they say. That when you touch the sky you accept it's all real. That no one is climbing Everest or Logan again. That Calgary, Mexico City and Madrid

are just gone. That whoever was in a plane or penthouse when the sky fell is never coming down. That no more planes are ever going up. No more sunsets or starry nights or full moons. No more night or day. No more summer-fall-winter-spring.

Touch the sky, they say—the people who have—and you can let it all go. Let go of 20 years of daily piano and violin and clarinet practice. Let go of that desperate dream of making a living in the arts. Let go of any hope of attending one of the last remaining Fine Arts schools. Any hope of one day having your own orchestra.

Just touch it. Accept it. Accept there's no longer a place for passion or grief or heartache or joy. The world is what it is. There's no need any more for creation. The sky fell and we survived the year of panic and wasted effort and now we know better. We know there's nothing we can do or control and we know that nothing means a goddamn thing anymore.

I reach in my pockets for the letters, hold them out before me and open my fingers. The hot wind catches the pages, spreading them across the wooden deck, to the edge, over it.

The teenager watches them go and then yanks loose his tie. "Fuck this," he tells no one. He balls up the tie and pitches it over the railing. Without once looking skyward, he stomps down the steps.

The staffer who escorted us up appears at the steps, her uniform as gray as the sky. "Time is up," she announces flatly and motions for me to come down. I obey. She takes a place by the elevator doors, hands clasped before her, impassive. The others wait—calm, docile.

I begin to whistle low, a composition of my own in E flat. The kid nods along, tapping his legs with his palms. He follows the rhythm through its asymmetric 5/4 meter, his beats growing increasingly complex. I have a moment to admire his talent before I catch the glare of the man in the Harley shirt, the irritated shuffle of the business types, the frown of the peroxide blonde.

My instinct is to stop out of politeness. I look away and force myself to keep whistling.

The elevator pings, ready to take us back down to the street.