Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author. She's a British Fantasy and Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy Award finalist, and a finalist in the Shirley Jackson, Philip K. Dick Award, Kate Wilhelm Solstice Award and the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans. Eugen is an Otherwise Fellow, and was also announced in the honor list for 'doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction'. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List as a 'sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work'. Visit her at eugenbacon.com.

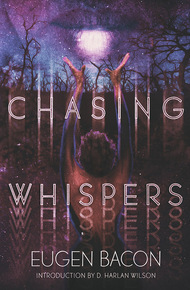

Chasing Whispers is a finalist for the Foreword Indies, has been shortlisted for the British Science Fiction Award and was on the 2022 Locus Recommended List

Chasing Whispers is a unique Afro-irrealist collection of Black speculative fiction in transformative stories of culture, longing, hybridity, unlimited futures, a collision of worlds and folklore. It contains 13 stories, 11 of which are original, with a commanding introduction by D. Harlan Wilson. The collection is aligned with the themes of Eugen Bacon's other fiction, and her recognition in the honor list of the 2022 Otherwise Fellowships for "doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction."

Chasing Whispers casts a gaze at mostly women and children haunted by patriarchy, in stories packed with affection, dread, anguish and hope. The connecting theme is a black protagonist with a deep longing for someone, someplace, something… and a recurring phrase in each story: "a deep and terrible sadness."

African Australian author Eugen Bacon, British Fantasy Award winner and Philip K. Dick Award finalist, crafts stories that challenge with their formatting, disorient with their strangeness, span multiple genres, fuse the modern world with African folklore, and move readers with their deeply-felt emotions. Chasing Whispers assembles thirteen of her unforgettable, poetic, tragic, bitingly humorous stories in one sublime package. – Mike Allen

"Described as Afro-irrealist speculative fiction, Bacon's newest story collection makes a lasting impression, delivering unique takes on body horror, technological advances, and existential dread."

– Booklist, starred review"In some ways, these are not stories, but emotions made flesh…Chasing Whispers is an emotive, immersive short story collection whose entries trade between being entertaining and thought provoking."

– Foreword Reviews"Chasing Whispers challenges the reader both in form and content. Bacon speculates with the form of the short story just as much as the stories blend together African folklore and the modern world. SF readers are frequently travellers in the past, present and future. We are all invited to explore the uncertaintes of humanity in this engaging collecton of short stories from Bacon."

– The BSFA ReviewNamulongo and the Edge of Darkness

A Lot of Selfless Running

A SEA GHOST grips Namulongo's hand in a place of lost and found. It wisps in and out in fog, its floating mist swallowing her fears. It ebbs and flows, reacquaints itself with shadow and hiss, sound and image in unevenness that's a questioning, and also a learning. But what's not learning is the fog's growth. Each year's swell is disproportionate to its past. What's not learning is the sea ghost's warmth, how it slips in night and day as Namu tosses and turns in her sleep. What it gives is solace in a familiar face of ambivalent light. At the distant edge of her distraction, the fog dances and smoothes her flaws. It stretches her to a wakefulness that's the best for now, guides her into a chapel that has an altar and a grimoire, and then down the basement to a sweeper that's crawling the ocean.

Namulongo's mother knows about her dreams. This is fact, Namu knows. So she doesn't tell her mother everything, especially in the gut of a chore, like now.

"Eee, pampula," exclaims Maé. "What a season you're having, child. I've never seen you guide the sweeper to this big a catch."

"Maybe I was just lucky."

"Luck has nothing to do with it. You've come of age and simply know how to harvest."

"My life feels like a lot of selfless running."

"And that's a selfish thing to say." Maé clicks her tongue.

"I'm just saying—"

"Well, don't."

Namu follows closely, imitates her mother's cleverness with the fish. Maé's hands move swifter with annoyance, her eyes wearing the blackness of a rare pearl, a deep, deeper, deepest ebony. Her eyes gleam silver when she chants before the altar. Maé is a magus of the coven, but she never magics the fish. With Namu by her side, who needs a chant to catch a good harvest from the ocean?

They work tirelessly and isolate the thrashing fish trapped in Submerse's sweepers.

"This one you let go." Maé uses the gentle picker to prong the wolf-fish and its terrible face down the pressure shoot, and back into the black waters.

"I know, Maé."

"You know, because I'm a good teacher."

"Yes, Maé."

At nine cycles, Namu knows a lot about the ocean and its creatures. She knows enough about Submerse, her underwater home, and the chores it insists she performs. She bustles from dawn to dusk, bow to stern, running, running in its tight quarters segmented into compartments.

The workshop is one compartment. Here, they make and recycle water, some from the facility that flushes open-valved with a pressured tank. The sleeper is a tiny unit. Here, they take turns in alternating sleep—it's called a warming, where Namu sleeps just off her mother's waking, her warmth on the bed still. It's a shared bunk bed and there's an equally shared locker full of handwoven thermals. The cooker is both a kitchen and a diner. It's next to a hive that has brown bees, all fuzzy-bodied, black-striped. The hive is honeycombed, its honey full of nuts, spice, ocean and smoke.

Near the cooker is a veggie patch. It's more spacious inside than one might expect, and it's reminiscent of something Namu remembers, then forgets. It's as if the growth of each new plant or habitat reinvents the veggie patch, mutates it to optimal conditions. The patch has miniature coconuts that yield sweet and sour water and cream flesh when you crack them. It grows wild lettuce, green tea, chilli pepper, black pepper, baby arrowroot, black nightshade, stinging nettle, shona cabbage, red eggplant, native sunflower, and all. The oxygen chamber has an electrolysis machine that winks green to show the oxygen is right. In the engine room, there's a spare battery and a powered generator that steers Submerse through the oceans.

"The moon, the stars—they're our friends," Maé always says.

In the comms room, when the signal is right, Auntie Azikiwe flickers in and out from her enchanted prison. There's a bridge at the top of Submerse. The vessel surfaces at dusk, and the watchtower has a periscope for Namu to study the world.

Maé expects much, and Namu gives it. She's good at scrubbing the hulls and the showers and the chambers. She paints to keep Submerse's tough steel from rusting. They don't have a titanium vessel like Aunt Umozi's. The same Umozi who, in her cunning, commandeered Auntie Azikiwe's submersible and all its power, reinforcing her own physical and charmed supremacy. Aunt Umozi wants Maé and Namu dead. She flickers in and out of the comms transmitter display when she breaches the vessel's firewall, or a surface drone catches a roaming signal. Namu has seen enough of the laughing face and its white, white teeth—let alone her mother's jumpiness when they appear. She's heard enough of the displaced sound to know that Umozi is abysmal, and it started with the Fallout.

Maé will not speak of the Fallout. But Auntie Azikiwe, when the drone picks a signal, and if Maé is absent, has hinted of it. It's a Fallout that happened way before Namulongo, and has cascaded to worse. All Namu knows is that she and Maé are outcast, and Auntie Azi is held captive in her own submerse. All of them are in grave danger. From what Namu has gleaned from stolen conversations, Umozi has grown more powerful since the Embodiment, but no-one will explain the details.

"Can't you get back in favour?" Namu once asked Maé.

"That's beyond question."

Today, Namu looks at the sweeper's harvest. She isolates the fish in buckets. She remembers everything Maé taught her, because Namulongo is a curious one. And curiosity is good for learning. She isolates fish by shape and hue. The silver and blue of the baby bluefin. The treble fin of the mud-coloured cod. The untidy splotch of the flounder. The sleek line of the silver bass. The leopard spots of the trout. Today is a very good catch.

Some play dead fish. Stun those first. That's what Maé likes to say. Hold them by the tail, give a solid whack on the head. Or if you know where the brain is, pierce it with a blade tip. Namu knows where the brain is. Sometimes an auto-stunner does the job. Put the head in first. It's humane that way. Because playing dead means being cunning. And that kind of sly means the fish's woe is more. They know if you pour an ice slurry over them, and play deader, until they can't. It's cruel to suffocate fish. To see them gasp for air and convulse. To see them contort their bodies until the thrashing goes weak. Behead quickly, gut, says Maé. Or just gut. Vertical along the base, peel the tail back. Pull the guts, bone the fillet. Now the fish is really dead. And fresh. Leave the carcass in the cool reefer, until it dumps the smell of the ocean.

"Go and have a splash," says Maé.

"But I washed this morning."

"Eee, pampula. I've never known a girl to hate water. We have lessons, soon after, no?"

"Yes, but—"

"But nothing. You purify to cast a spell. And, after the lesson, dinner."

Maé doesn't get that it's not the water that Namu dislikes. It's the restraint that comes with it. Drip, drip. Recycled, drip. From an early age, Namu has understood that what she needs is tiny wetness, turn off the faucet. Soap, drip, drip. Dry. Even brushing her teeth is on drip, drip. Wet the brush, turn the water off. Brush to and fro, remember the tongue. To and fro, don't forget the cheeks. Spit, turn the water back on. Drip, drip.

Namu is a water creature. It's torment to withhold water for one whose spirit is water. So she avoids the washing in the manner her mother demands, same as she dislikes sleeping. The bunk is a coffin. Her awareness of the tomb that is her home is big, because that very home also drifts through the ocean and its endless flow.

Isolate the Flame from the Wick

Namulongo and her mother kneel by the altar inside a candle-lit chapel.

"I'll teach you to light the flame different," says Maé.

"Why?"

"Your borrowed spell is lacking. Soon, you must whisper your own chant, not mine."

"But I don't have an incantation."

"You'll find it."

"How?"

"Sometimes people dream an 'own' chant. Sometimes you create one."

"I don't need magic language. Maé, I don't want to become a magus."

"You're born to the coven."

"Am I, Maé?"

"Eee, pampula. This sacred place is not for arguing. Fetch me the grimoire."

Namu lifts the magic tablet from its lectern, left to the altar. She hands it to Maé, seated cross-legged on a carpet of cured antelope skin.

"What did I teach you about this text?"

"It's a book of shadows. It has your thoughts, recipes, spells, rituals and hexes—every single one of them personal to you."

"Soon we'll start on your grimoire. Now do as I do."

Maé rolls her eyes and begins to shudder in a chant:

Inasa bwira

Nada ina.

Flames go out in the array of candles. "Light them again."

Namulongo casts her hand, palms out as if to summon, or to channel. She gazes inwards, sways in a chant:

In asa bwi ra

Na da ina.

The flame on the wicks flickers weakly.

"Walk me through it," says Maé. "What are you trying to do when you spell?"

"What you asked. I want to make the spell talk."

"Eee, pampula. That's what is going wrong. You need to talk the spell. You must become the spell—don't think yourself through it."

"I don't understand, Maé. I never will."

"A spell is about belief. Feel it here." Maé touches Namu's head. "And here." Namu's chest. "And here." Namu's stomach. "Now straighten up and do it right."

In asa bwi ra

Na da ina

"Better. See how the flame is bold? This time I want you to toss it."

"How?"

"Isolate the flame from the wick."

In asa bwi ra

Na da ina

"Say it like you own it. Draw deep, then breathe your intent in a quick release."

In asa bwi ra—

"Child, there's not enough on your breath. Your throat is not even moving. You need to hang onto belief until the spell homes."

"I'm trying, Maé!"

"Try harder. On a battlefield if you leave a spell hanging, enemies will pounce. They read you like their own grimoire."

In asa bwi ra—

"Where's your conviction?"

"I'm doing my best. How can I succeed if you keep intruding?"

"Because it kills me to see you doing it wrong. You have the right 'initiate'. What you need is a good 'finish'."

In asa bwi ra!

Na da ina!

Namu heaves forward and throws her arms. Orange-blue flames surge from the wicks. They shoot to the chapel's tough steel roof, and flutter in a sizzle, dead on their fall.

"Child." Maé lays a hand on Namulongo's shoulder. "The spell has too much carry. You lost your temper."

"Then stop pushing me!"

"Know composure, even in distress. Never let the enemy read your weakness."

"It's hard to find the craft when you don't want it."

"Feel the spell."

"I need time to settle, Maé."

"Composure is all the settle you need."

By the end of the lesson—Maé still pushing her relentlessly into the world of spells—Namu is spent, body and mind.

"The best time to find your core in a spell is when you need it the most," Maé is saying. "Endure the challenge—an attack can happen quickly. Sometimes all you need is to keep the enemy at bay, until help arrives." She ruffles Namu's plaits. "That's the last lesson for today. Accept when you need help. Now, go take a nap."

"You said dinner after. I'm not little anymore—I don't need naps!"

"Even while I surface Submerse, then you'll wake for a swim? Trust Bibi, she'll guide you."

The fog of Maé's familiar—the sea ghost—envelops Namu. She finds herself in the bunk bed, her mother's voice a whisper in the distance.

A nap is not a game of statues, just a holding of breath. Sleep, child, in the season of the oceans. Today is upwelling. Seabirds nest and, when you rouse, you can watch whales leaping in the rise and fall of spring winds. I'll make you a flower pickle that protects you from the edge of darkness. Hibiscus petals, sunflower oil, vinegar, thyme and garlic, all sealed in a jar with a spell of origin and conquest. One lick will sigh out the blackness after sundown. Next lick, it'll march you to the horizon, out to see a victory. The battle belongs to you, child. Bloom, bloom, this moonlight, sleep in the ocean's belly.

Maga kasi… Osi osi.

A sea ghost hums this.