I live in Chicago with my husband and two cats. I bike, swim, garden, attempt yoga, and find new uses for old sex demons. You can get 5 free "horns headband" tattoos by sending a self-addressed, stamped envelope to Jennifer Stevenson, PO Box 6411, Evanston IL 60204-6411.

Aren't you tired of doing everything right?

Wouldn't you like a second chance to go back and do it wrong?

Cricket's family may be ready for their 98-year-old great-grandma to go gently into that good night, but she sure as hell isn't. So when hell comes calling in the form of Delilah, she's ready to sign on the dotted "succubus" line.

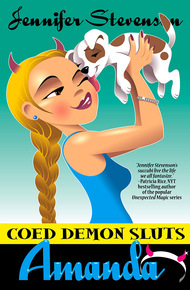

Army brat Amanda has spent her life letting everyone else call the shots. With a shiny new contract, and a shape-shifting body as tough as titanium, she's ready to call some shots of her own–on the basketball court.

Now roommates at the Lair, this odd couple are ready to set the Regional Office on its ear with history's first coed demon basketball tournament–and to discover that you're never too old or too shy to find new friendships–or love.

The fourth adventure in the Coed Demon Sluts series!

"This is a thought provoking story wrapped in humor. I'm looking forward to the next one."

– Reader review"A very poignant and heartwarming story, lots of emotion."

– Reader review"Jennifer was trying for a sweet love story and in inimitable Coed Demon Slut style she has achieved that. I keep wanting to say "this is the best yet" but all the books are so different that they are all "the best book yet.""

– Reader reviewCricket

Cricket Immerzang sat silent at lunch at the Loriston Home. It wasn't her nature to be silent. Normally she was talking. That's how she'd got the nickname. Cricket didn't mind. She took an interest in people. She let them feel noticed. Today, though, she felt unsure of herself, a very rare occurrence.

"Spent it all on that new wife of his," Zilla Barrett was saying. "Can never remember her name."

It's your son's money, Zilla. And his wife's name is Isabel, same as your mother's, which is why you don't remember. She's not a bad sort. She came out here for Fourth of July brunch to see the fireworks with you. She makes your son happy. She'd like to make you happy, too.

Good luck with that. Zilla was heavily invested in her unhappiness. For once, Cricket held her peace.

"I've told them and told them," Xavier Holz was saying at the same time, across the table. "I can't have anything with soy in it. Makes me sick. You remember how sick I was. Told them and told them. Sick as a sheep," he added, ignoring Zilla's complaints. "I had to go to the infirmary." He shuddered. The oxygen tubes running into his nostrils shuddered with him.

Cricket forbore to point out that the infirmary was pretty good here. You got prompt attention and you almost always felt better right away. Not like the second floor. Nobody wanted to go to the second floor. People went there and stayed.

No point thinking about it. Not until the middle of the night anyway.

Meanwhile Wanda Toot was retailing a fresh horror. "The elevator doors opened and I saw her. In a wheel chair. On the second floor," she hissed. "They had those mittens on her hands. So she can't scratch herself." Wanda didn't quite believe in the second floor, She was younger, in better shape than most. She was working her way around to thinking about it, though, by cataloging the horrors perpetrated on people she knew. She preferred to think of them as wrongs done by the medical profession, not as inevitable calamities.

Cricket was aware of her own dodges and denials about the second floor. She was ninety-eight. She had buried three husbands and all their children. Cricket's simple resistance was her bucket list, a list that got longer every week. She read widely, surfed the internet, and watched action-adventure movies, so she was able to keep that bucket list growing. Her creed was that until she got to do it all, she wouldn't go.

Lately she'd been hearing the denial in her own voice, especially at three-forty-five in the morning. She'd lie awake wondering about death. Everyone here resisted death in their own way. When they started to embrace it, they tended to slide to the second floor quicker. Sometimes they just went: healthy-ish one day, the next... boom. Was that better? What had her husbands learned, at the last moment?

It would almost be worth it to die, to find out. Almost.

Alban had been devout, which meant he thought it was over, finis, nothing happens, the end. That was a hell of a note. Lucien hadn't cared. He went boom, too. Irving was completely unreligious, though he'd begun to wonder, toward the end, and he'd been grateful to leave the lung cancer behind.

In ninety-eight years Cricket had seen a lot of leading-up-to-death, but she hadn't seen death. What happens next?

In the wee hours, she would spend a few minutes thinking all these things, even though she had thought them every night for many years, and then she would turn over with a sigh to worry about all the other stuff she didn't know. Politics. How to keep her granddaughter Sharon from talking to her doctors. When, if ever, she would feel she belonged here. What body part would fail her next, and what functioning she'd lose with it.

Finally, at four-fifteen, she would feel a click in the back of her skull somewhere and then she'd fall asleep. She called it her worry-wart popping. But it didn't seem to matter what she thought about. For half an hour every night, she lay awake, feeling anxious and vigilant, while nothing happened.

Cricket believed in truth and kindness, two wildly opposing ideals that made conversation with her, she was aware, a test of patience sometimes. She couldn't go changing her chatterbox habit at this time of life. She stayed positive.

So she didn't complain, and she didn't talk about death, or the nearest thing, here at the Loriston Home.

Somehow there was always a bed open on the second floor. That's how you knew how bad it was. Other floors, you had to wait months for an apartment. Loriston Home was a very nice facility. But the second floor was what it was all about. A graceful transition facilitated by expert and well-meaning staff.

She loved the staff at Loriston. She really did. It was just that they were so young.

Nor did she have a right to feel lonely. Her grandkids and great-grands were attentive. Yet, when they were here, they acted nervous. The place scared them wall-eyed. She supposed that tolerating it was a knack, like living on a volcano slope or next door to a glacier. You never knew when it would roll over everything you knew. You got used to it. And if you were one of the people who didn't have to think about glaciers or volcanos yet, you pretended there weren't such things.

Cricket thought glaciers and volcanos were interesting. Apart from the bit where they eventually obliterated you.

After lunch, she changed into her bunny-printed sweatsuit and spent a pleasurable hour in the community garden out back, pulling weeds, staking up tomato plants, staring into the bean vines. The longer you stared, the more you saw. The beans became a titanic jungle canopy where ants crawled like prehistoric monsters. The bean stems twisted and sometimes split. Overhead, cicadas sang like a million tiny chainsaws. At length she got dizzy from bending over, and returned to the air-conditioned sameness of the main building. She took a moment to be grateful for having seen the ants. It drew the sting out of having to go in early.

"You have a visitor, Cricket," the front desk girl congratulated her when she went to pick up her mail. "I told her you were out in the vegetable garden. She's waiting in the North Lounge. A Ms. Dee Lilah." The girl handed over a business card.

Cricket turned it over, bemused. Black business card with red leaping flames around the name, Delilah. The flames seemed to move. Wow, fancy.

She took a moment to be grateful for the tomato-plant smell on her fingers.

Then she walked into the North Lounge.

~~~

"Not buying it. Sorry," Cricket said, after Delilah had been talking for ten minutes. Girl was a good salesperson, but there were big holes in her story. "If you work for hell, how come you're offering to pay me? By the way, that's a really nice dress. Suits you."

The dress was red leather and very flattering to the woman with one name. She looked to be about forty, green-eyed, with thick, straight, beautifully-cut dark hair, her olive skin slightly weathered but still sleek. She seemed utterly self-possessed.

Delilah ignored the compliment. She lifted an eyebrow. "I thought you'd be more worried about keeping your soul."

Cricket waved that away. "Nuts. I don't believe you can take my soul any more than you can take the sky. If you could take it, you'd take it. You wouldn't be trying to bribe me. By the way, thanks for the chocolate. Tasty. Have some?"

The smooth young woman stared at Cricket as if exasperated. "How do you figure?" she said weakly. She reached over and broke off a chunk of the fancy-dancy chocolate bar she'd brought Cricket.

"Hah. I watched the advertising industry grow from a peanut. I know you put glitter on the product when the product is something nobody needs. And you use extra sprinkles when the whole deal doesn't really exist. In my seventies I got a lot of door-to-door salesmen and religion peddlers," Cricket added. "Who knew that would be such good practice for talking to you?" She was tickled that all those hours killing time with the nice Mormon boys were turning out useful now.

"Most people don't want to listen to a sales pitch for something they know they don't want," Delilah said around her bite of chocolate.

"I like talking to people."

Delilah sat and stared at her. Cricket could almost see her flipping through flashcards in her head, looking for one that would work on this chirpy little old lady.

Cricket nudged. "Come on. Haven't you got any more ideas?"

She felt weirdly exhilarated. This was like the second floor conversation, only the opposite. Delilah wasn't trying to sell her salvation, or eternal life after death, which most people said was all puffy clouds and harps, but which they really believed was like going to Disneyland or the mall, only you never had to pay, and it never closed. Nobody had ever tried to buy her soul with something she actually wanted before. New experiences were meat and drink to Cricket.

"What part of it doesn't make sense?" Delilah said at last.

Cricket opened her palm. "You know you can't really buy my soul. And yet you're offering me all this great stuff—new young body, money, housing, and a job being a—a—"

"Succubus. Sex demoness. Very fancy, very highly paid prostitute."

"And you get what out of this? People have sex for free all the time. You don't give them all this stuff."

"It's field work," Delilah said helplessly. "The Regional Office knows you have to pay women to have sex. We have thirteen hundred demon desk workers for every demon field operative. Attrition in the field is crushing. And frankly," she admitted, "we don't have the customer base we used to have."

"You're saying nobody believes in hell anymore." Cricket was delighted. She hadn't had a conversation this crazy since before Seymour Leskin went on those pills.

Delilah shrugged. "Not really."

"Tell me about attrition in the field," Cricket said.

"There's hardly anyone left in the Lust Division. We're especially low on succubi—female sex demons. That's the Second Circle of hell if you're Catholic," she added.

"Do I look like a shiksa?"

"Male sex demons hang around for centuries. They love their jobs. For some reason, the women don't stay. Second Circle is only a way station for them. They have stuff to work out, they do the job for a while, they move on. At this point, we have more dead accounts than working field operatives."

Light dawned for Cricket. "It's a bureaucracy."

Delilah whooshed out a breath. "You have no idea."

"So do you have computers?"

"Ugh," Delilah said.

Cricket was pleased. Whoever she was, this girl was a sound thinker. "Tell me, do you get anything out of your job? Personally?"

After a moment, Delilah said, "Make you a deal. You tell me what would possibly interest you in my offer, and I'll tell you what's in it for me."

"You first," Cricket said.

Delilah burst out laughing. "You are such a tough prospect!" She cocked her beautiful dark head. After a long look at Cricket she said, "All right. This is between you and me."

"And why would you trust me?" Cricket said.

"You have no one to tell. You'll probably never meet your supervisor. We quit running quality circles with field operatives decades ago, because they wouldn't put up with it." She gave Cricket a warning look. "I don't know why I'm telling you this." She breathed in, sighed out. "One of my field operatives has been on the job too long."

My field operatives, Cricket noted. Not our.

"She's stuck. She shows signs of getting restless, but I think she needs a little push. To get out of the nest."

Cricket's mouth fell open. "You're running a stealth op inside the Regional Office."

"What?" Delilah squinted. "Where do you get that kind of language?"

"I watch a lot of old Tom Cruise movies, and don't change the subject. You are, aren't you. I bet you're responsible for all those field operatives quitting. You want me to get this one you're talking about to quit?"

Delilah turned red. "How—wait, what—?"

"Well, you said, 'one of my field operatives,' and you said she needs to get out of the nest. You hate the bureaucracy. I bet you're not even in their computer, not properly. But you put people on their payroll. So you're sucking them dry financially, too."

Delilah eyes narrowed. "I'm not telling you anything."

"That's okay, dear." Cricket reached forward and patted her hand. "I didn't think you were anyway."

Delilah laughed. "Your turn," she said firmly.

Cricket folded her hands on her lap and stared off into the distance. She had tried not to think about her future on the second floor—much—except between three-forty-five and four-fifteen in the morning—but when she did, it was always in terms of her physical capability. Mobility, autonomy, agility. She was so accustomed to being grateful that Delilah's million-dollar offer had completely surprised her, in spite of the ridiculously long bucket list.

This was a whole new kind of list.

"Well," she said, staring through the North Lounge wall at the world full of things she would never, let's admit it, Cricket, ever do. "I want to bungee jump. I want to dye my hair purple and green and pink and orange. I want to roller skate. I want to dance again, and learn some of these new dances. I want—"

She stopped and stared harder through the wall. Delilah's offer was very specific. Fancy young new body and all that money and stuff for sex.

It occurred to Cricket that she'd left a lot of things off that bucket list.

"All my granddaughters used birth control by the time they were seventeen. My great-granddaughters have studs in their tongues."

Delilah didn't answer that. Cricket liked that she kept quiet so a person could think this through.

"It's not that I haven't had fun. Because I have. I had three husbands and four kids of my own and six step-children, and I have twenty-four grandkids, almost forty great-grandkids. That's a lot of fun."

"Sounds like a lot of work to me," Delilah said bluntly.

"Of course. Fun is work. The only fun that isn't is drugs, and that gets old fast." Cricket waved a hand. "What I'm saying is, I did all the things I was supposed to do. I had the fun a good girl has."

"Ah." Delilah looked as though she could see that flashcard clearly now.

"I don't take harps or hellfire seriously and I'm not interested in keeping score. But it seems to me—" That new bucket list unrolled in Cricket's head. Stuff she hadn't thought about since Irving died. The rest of her might be pretty rickety, but her heart was young.

Delilah leaned forward. Here it comes, thought Cricket. "We can walk out that door right now. You won't ever have to come back."

Cricket heard the elevator doors open down the hall. Someone went by, pushed in a wheelchair by an orderly. The patient was wearing bulky white mittens.

"What are we waiting for?" she said.