James Morrow is the author of the World Fantasy Award–winning Towing Jehovah, the New York Times Notable Book Blameless in Abaddon, and the Theodore Sturgeon Award–winning Shambling Towards Hiroshima. His most recent novels include The Asylum of Dr. Caligari, The Madonna and the Starship, The Last Witchfinder—hailed by the Washington Post as "literary magic"—and The Philosopher's Apprentice, which received a rave review from Entertainment Weekly. A master of satiric and the surreal, Morrow has enjoyed comparison with Mark Twain, Kurt Vonnegut, and John Updike. He lives in State College, Pennsylvania with a collection of Lionel trains and a rapidly growing library of DVDs of questionable taste.

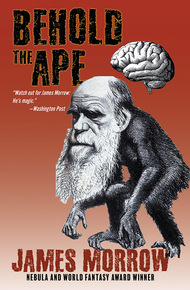

An acerbic, entertaining caper of evolution, gangsters, Darwin's brain, and the Golden Age of Hollywood.

When Sonya Orlova, a successful 1930s horror-film actress, crosses paths with a gorilla whose brain has been swapped for the frozen cerebrum of the late Charles Darwin, the two are inspired to write and produce evolution-themed monster movies—with Sonya in her greatest role, Korgora the Ape Woman!

As this offbeat and controversial Hollywood series finds a devoted cult audience, Sonia's relationship with her strange simian collaborator acquires an intensity neither could have imagined.

Then disaster strikes, as zealous opponents to Darwin's ideas contrive to put the Ape Woman out of business.

By turns satiric and romantic, madcap and thoughtful, Behold the Ape is at once an outré love story, a tribute to classic monster movies, and a science-fictional celebration of that beleaguered institution we call public education.

"James Morrow is a wildly imaginative and generous novelist who plays hilarious games with grand ideas."

– New York Times book review"Watch out for James Morrow: He's magic."

– The Washington Post"It's called satire, and James Morrow does it brilliantly."

– SF Site"Satirical romp? Affectionate tribute to 1930s monster movies? Savage indictment of religious fundamentalism? Though imaginary, Morrow's great actress Sonya Orlova — the woman of a thousand faces — certainly deserves cinematic immortality, if only for her signature roles as the vampiric Countess Nocturnia, Golemoiselle and Korgora the Ape Woman. In these pages, however, Morrow relates the story of the ape into whose body Sonya's unlicensed neurosurgeon brother secretly transplants the long-frozen brain of Charles Darwin. Adopting the stage name of Ungagi the Great, the simian "Mr. Darwin" eventually joins Sonya as her co-star in a half-dozen trashy classics of "Australopithecinema." As one character approvingly remarks, "Florid is fine, but lurid is better."

– The Washington PostChapter 1

The Woman of a Thousand Faces

Wherever you go, she is there. The famous monsters she created appear on postage stamps, T-shirts, lunch pails, beach towels, and mouse pads. The estate of the late Sonya Orlova has licensed her likeness, in all its iterations, to the makers of action figures, plastic model kits, collectible dolls, soft drink cups, and PEZ dispensers. Such is the legacy of Hollywood's premier horror movie actress of the 1930s—though Sonya herself would have told you, in her mesmerizing, waltz-tempo Slavic accent, that her proudest achievement was teaching filmgoers, without their even knowing it, a thing or two about the mystery of human origins.

Any serious student of popular culture can recite Sonya's signature roles without skipping a beat. Countess Nocturnia, who could transform even the most willful lover into a willing blood donor. Golemoiselle, wrought from sacred clay and secular hubris. The She-Wolf of Paris, who took such erotic delight in her lycanthropic condition. And then, of course, there was Korgora, the Ape Woman, protagonist of five low-budget melodramas that prevented Sonya's adopted country from descending into barbarism—or so certain social historians are prepared to argue.

Born in Smolensk at the turn of the twentieth century, Sonya didn't understand at first why, two months after the start of the Great War, her hardworking, land-owning parents had gathered up their five children—plus heirlooms, photographs, and a satchel of silver coins—and sailed for New York City. Once they'd settled in the tenements of the Lower East Side, however, she began eavesdropping on Mamuska and Papa's late-night conversations, and she came to appreciate the wisdom of their decision.

Had the family stayed in Russia, they would almost certainly have gotten caught in the crossfire of the Bolshevik Revolution. Indeed, during the months leading up to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, and throughout the civil war that followed, nearly everyone her parents knew back home had been murdered outright or banished to a labor camp. Typical was the case of Mamuska's mystically inclined aunt, executed for aiding the Tsarina's debauched mentor, a notorious figure whose life inspired Sonya's last film, Horror of Rasputin, in which she played the mad monk's preferred companion, a gorilla.

For years she lived at home, supplementing the income from Mamuska's laundry business and Papa's bicycle repair shop by working as a taxi dancer at the Blue Moon Club on the other side of town. Her older siblings, meanwhile, were privileged to venture forth from Manhattan, Andrusha becoming an elementary-school teacher in Brooklyn, Yuri a dairy farmer in New Jersey, and Vasily a carpenter who, when not attending a small college in faraway Los Angeles, earned good money building motion-picture sets. Although Sonya envied her brothers their escape from the tenements, she was content to bide her time, fending off the advances of the Blue Moon clientele even as she charmed them into helping her master the bedeviling English language.

In the autumn of 1920, something happened that changed Sonya's life forever. She chaperoned her little sister, Tatiana, to the Bowery Nickelodeon and thus inadvertently saw her first horror movie. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starred John Barrymore as a scientist who sought to liberate his inner Lucifer, plus Martha Mansfield as his lovelorn fiancée and Nita Naldi as the music hall floozy with whom Jekyll's lecherous other half carries on a lurid affair. According to the program notes, Barrymore had accomplished the first transformation without benefit of make-up, relying solely on his ability to twist his pliable face and contort his spidery body. The plot was equally enthralling, so tragic, so wrenching, so worthy of her tears: poor, deluded Henry Jekyll, thinking he could have it both ways—philanthropic physician by day, sybarite by night, blithely oblivious to the disasters he was courting.

"I could play that part," Sonya remarked after the picture as she and Tatiana sauntered through the lobby. She indicated a lithographed Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde poster resting on an easel.

"The fiancée?" said Tatiana. "Of course! Martha Mansfield is pretty, and you're even prettier."

"No, not the fiancée."

"The music hall lady?"

"Not Miss Gina," said Sonya. "The monster."

"Edward Hyde?"

"Let's call her Edwina."

"What about Henry?"

"You mean Henrietta?" said Sonya. "She's a crashing bore, but I'd be willing to play her for the sake of becoming Edwina. Put me in front of a camera, and my wicked Lady Hyde will make grown men shit their pants."

"Sonya!"

Because her eldest brother was still nailing together Hollywood scenery for a living, her notion of insinuating herself into the movie business struck Sonya as only moderately preposterous, and so with her parents' reluctant blessing she traveled by train across the North American continent, bound for a city she imagined would prove as gloriously decadent as the Spitalfields district of Hyde's nocturnal ramblings.

Shortly after appropriating the spare room in the cottage her brother was renting in El Sereno, she realized she'd made a mistake, for in becoming Vasily's tenant she'd also become his captive audience. An angular, elfin man with wild eyes and untamed hair, Vasily spent his nights railing against humankind's collective stupidity and God's monolithic indifference. Depressingly for Sonya, Vasily no longer orbited the movie business, having been, as he put it, "improperly fired for allegedly drinking on the job." A year earlier, he'd managed to graduate from Occidental College, then somehow got accepted to the Pasadena School of Medicine. He'd dropped out after six months, and yet, in his gin-fueled delusions, he was convinced he'd eventually become as competent as any credentialed doctor.

"In two or three years I'll have mastered more human physiology than half the instructors at the Pasadena School. Give me a talented amateur over an uninspired professional any day."

"But how will you acquire actual medical knowledge?" asked Sonya.

"I still have my textbooks, and I can attend the lectures at Mercy Hospital incognito."

"Lectures by uninspired professionals?"

"This is a brilliant plan, dear sister. Someday you'll understand."

Because Sonya's taxi-dancer experience transferred readily to Los Angeles, she eventually saved up enough to escape from Vasily's sphere. She signed a lease on a Culver City bungalow in which roaches were forever showing other roaches around the place. Despite these seedy accommodations, her spirits remained high. Before long she acquired not only a boyfriend, Homer Chilton, who wrote the popular science-fiction radio drama series Ticket to Tomorrow (they met standing in line to see Lon Chaney in The Unholy Three), but also a reasonably honest manager, Barney Garland, and eventually she broke into the business—first as an extra, then as a bit player, and finally as a name in the credits.

To whom did a casting director turn when he needed someone to essay the ingénue's simpering best friend in a cliffhanger? To Miss Orlova, of course. The French goose girl in a Great War spectacle? The callow young hero's slut-on-the-side in a domestic melodrama? The pitiable harlot in some high-minded attempt at social realism? Indeed. While this was hardly the career she'd imagined for herself after falling under John Barrymore's spell, she resolved to continue playing incarnated plot necessities, taking every opportunity to learn about those technical elements—camera angles, lenses, lighting, filters, gels—that could turn a performance into a phenomenon.

She even invested in a Max Factor make-up kit, complete with crepe wigs, false noses, spirit gum, greasepaint, and dental appliances. Every night she practiced the art of turning herself into a creature of darkness, devising her own interpretations of Gaston Leroux's sympathetic Phantom of the Opera, Aleksey Tolstoy's undead Wurdalak, Nikolai Gogol's demonic Viy, and, of course, Robert Louis Stevenson's soulless Mr. Hyde. And then, at the crack of dawn, she would dutifully report to the set, prepared to become whatever scatterbrained or promiscuous young woman was paying the rent that week.

Occasionally Sonya visited Vasily, hoping to rekindle the affection they'd known as children, but these days her brother regarded her only as a source of ready cash. Having moved to Santa Monica, he now occupied something called a Slipstream trailer, a kind of landlocked, aluminum-plated dirigible, though he was really living inside his head, a terrain of epic self-deception, or so Sonya surmised from their conversations in his kitchenette.

"My life is on track," he insisted, gesturing toward the medical textbooks stacked on the mattress. "I've read them three times over, and I've snuck into dozens of lectures, and next month I'll arrange to get listed in the Southern California Registry of Licensed Physicians, also the Orange County telephone directory. Vasily Orlov, MD—that's me."

"The instant prospective patients see this place, they'll run screaming," said Sonya.

"Until I have my own clinic, I intend to make only house calls."

"'Look, Mildred, it's the Angel of Death, come to pay us a visit.' How much do you want this time?"

"Lend me a hundred, and I'll own the Slipstream free and clear. I'll repay you once I have three or four regular patients."

"God help them."

"I'll pretend you didn't say that."

"I'll pretend you're about to become acquainted with reality."

#

In 1927 Warner Bros. released, to considerable success, The Jazz Singer, featuring lip-synched songs and a smattering of recorded dialogue, and soon almost everyone in Tinseltown was convinced that talkies would take over the industry. At her manager's urging, Sonya queued up for a Vitaphone screen test conducted by Excelsior Pictures—not exactly a Poverty Row outfit like Mascot or Tiffany but hardly commensurate with Paramount or Metro. The audition rules allowed Sonya to use her choice of material, so she performed her version of Dr. Jekyll's chemistry experiment. Like Barrymore, she transmuted into her second self without resorting to make-up, interpolating lines such as "You'll never control me, my pathetic Henrietta!" and "Lead me into temptation, my lascivious Edwina!"

Upon seeing Sonya's astounding metamorphosis, the president of Excelsior, Isaac Bachman, summoned her to his Gower Street office. "The camera likes you, darling," he gushed. "The microphone likes you better. The whole meshuggener world will love you. I'm sending Barney a contract tomorrow."

Playing a hunch, Mr. Bachman cast Sonya as the vampire protagonist in a horror movie he'd rushed into production with an unfinished script and an incomplete cast. His reasoning was simple. Variety had predicted that Universal's forthcoming supernatural fantasy, Dracula, starring Bela Lugosi, would strike a chord with audiences seeking a respite from the anxieties that, following the Crash of '29, had been visited upon millions of moviegoers. So why, asked Isaac, shouldn't Excelsior get there first?

"The picture's called Countess Nocturnia: Mistress of the Dead. You'll play a bloodsucker who's as beautiful as she is treacherous."

"Everybody in this town is beautiful," said Sonya. "I want to be unforgettable."

"How about beautiful and unforgettable?"

"Give me a weekend with my Max Factor kit, Mr. Bachman, and I'll reward you with a Nocturnia who's gorgeous, ghastly, and dangerous to know."

Guided only by her reflection in the mirror and a handful of sketches, Sonya turned her eyes into bottomless pools of menace, worked her hair into a coiffure as unruly as Medusa's, and outfitted her upper teeth with a denture suggesting a guillotine for mice. Homer the boyfriend called her Nocturnia make-up "a glorious obscenity." Mr. Bachman took one look and cried, "It's a by-God masterpiece! Mazel tov!"

Countess Nocturnia beat Dracula into theaters by three months and did surprisingly well at the box office. Even after the Lugosi picture was released, Sonya's vampire drew enthusiastic audiences. The reviews were mixed—whereas Daily Variety called the film "Grand Guignol in the grand tradition," the Los Angeles Times lamented its "penny-dreadful sensationalism"—but the profits were undeniable. Mr. Bachman credited Grant Ferris's efficient direction and Ray Erlich's moody photography, but he reserved most of his praise for Sonya's "brilliant acting and miraculous make-up."

Unsurprisingly, he lost no time developing Blood of Nocturnia and commissioning scripts for more such vehicles. She-Wolf of Paris had Sonya essaying a dual role as Belle Époque explorer Françoise Vicot and her silver-furred alter ego. The picture performed so well that Mr. Bachman immediately hustled Cry of the She-Wolf into production. Next came Golemoiselle: Creature of Clay, in which Sonya played a living sculpture animated by a deranged Kabbalist. Revenge of Golemoiselle followed in short order.

And so it was that she stopped being an actress and became an entirely different class of person, a movie star. Wilton Crabbe at Daily Variety said it best. "At long last Hollywood can boast a female equivalent of the late Lon Chaney. Sonya Orlova is our Woman of a Thousand Faces."

#

When Vasily appeared at Excelsior one sweltering July afternoon, wending his way among the plaster tombstones on the Kiss of Nocturnia set, Sonya realized he was the last person she wanted to see—and yet his frightened eyes and trembling hands aroused her sisterly instincts, and so she resolved to listen to his latest tale of woe. She'd just delivered an adequate reading of "No grave this side of Perdition can hold me" to her servant, Mordant, which meant Scene 14 was in the can. Mr. Ferris ordered the cameraman to cut, the property master to kill the fog machine, and the lighting technician to douse the kliegs.

"What a fantastic make-up job." Vasily wore a white lab coat, as if that gave him the authority to come crashing onto Hollywood soundstages. "Of course, nothing can top your Golemoiselle. I'm dying to see the next sequel."

"How much this time?" she asked.

"I'm not here for money. Sonya, do you believe in sin?"

"Yes. No. I don't know. What the hell kind of question is that?"

"I believe I've committed a sin."

"For whatever reasons, Mother Church never got her hooks into me, and I wouldn't exactly call our parents religious either. Why are we having this conversation?"

"A terrible, unpardonable sin. You're the only person I can talk to."

"It will take me an hour to get this crap off my face."

"There's a bar at the corner of Sunset and Talmadge. I'll meet you there."

By the time Sonya arrived at the Mesa Magnifica, Vasily was in his cups, contemplating an empty martini glass that could have served as a birdbath (the bar was celebrating the end of Prohibition in style). She joined him in the booth and ordered a glass of stout, the preferred beverage of Barrymore's Mr. Hyde.

"While you were on this side of town becoming a horror queen, I was also doing pretty well for myself," said Vasily. "I rented an abandoned sanitarium in Pico Rivera, converted the turret into a surgical theater—"

"So it's surgery now? Surgery?"

"Brain surgery, to be precise."

"Good God."

"I'll have you know that my assistant and I—"

"Another graduate of the Famous Surgeons Correspondence School?"

"A nursing student."

"Are you sleeping with her?"

Vasily rolled his eyes. "During the past eighteen months Nurse Cassidy and I have removed—"

"Nurse Cassidy? She graduated?"

"At the Orlov Clinic we don't fetishize diplomas. Our specialty is cerebral neoplasms. Thus far we've saved the lives of four Chinese laborers, but recently I've learned about the drawbacks of running a private neurosurgery practice."

"Second-degree murder?" said Sonya, wondering how she could talk herself out of turning Vasily over to the police.

"Two months ago I was offered seven thousand dollars to relocate a dead scientist's frozen disembodied brain into the skull of a gorilla."

"To do what?"

"Naturally I assumed the clients wanted a complete swap, one whole brain for another, but they told me to transplant the left cortical hemisphere only."

"Into a … gorilla?"

"An eastern lowland gorilla. His name is Zolgar."

"Half a frozen human brain?"

"My clients, a textbook publisher called Nigel Rowen and his brother—they told me everybody would benefit. Without the surgery, Zolgar was doomed—a malignant brain tumor—and the operation would give the dead scientist a new lease on life."

"Why did the Rowens have a frozen human brain in the first place?"

"They wouldn't say."

"For that matter, why were they keeping a dying gorilla?"

"Seven thousand dollars, Sonya. Now I can buy the place I'm renting."

"Something tells me you weren't your clients' first choice of surgeon."

"I severed the donor's corpus callosum as they wished, returned his right hemisphere to the ice chest, and transplanted his left into the ape's cranium."

"And what happened to Zolgar's diseased hemisphere?"

"Nigel and Desmond didn't want it, so I disposed of it discreetly."

"Why didn't they have you insert both of the scientist's hemispheres and give him an entirely new lease on life? Were they inordinately fond of Zolgar?"

"I've asked myself those same questions."

"This is all very disturbing."

"You haven't heard the worst of it." Vasily lifted the skewered olive from his martini glass. "The Rowens demanded that during the procedure I implant an electrode in the gorilla's medulla." He closed his lips around the olive and pulled it free of the toothpick. "I suspect they're shaping his behavior through radio-controlled shocks."

"Would you mind if Homer appropriated all this for the next installment of Ticket to Tomorrow?"

Vasily removed a Los Angeles Times clipping from the inside pocket of his lab coat: a full-page, lavishly illustrated advertisement for a traveling carnival called Pollock and Boggle's Peripatetic Panorama of Beasts, Freaks, and Prodigies. According to the promotional copy, the carnival with its "six stupendous sideshows" would occupy the Pomona Fairgrounds "for two thrill-packed weeks only."

SEE Eloise the Bearded Lady!

SEE Ling and Loo the Chinese Siamese Twins!

SEE Swami Gupta the Astonishing Hindoo Mind Reader!

SEE Zolgar the Gorilla Who Receives Messages from Heaven!

SEE Armless Jake Who Throws Knives with His Feet!

SEE Cornelius the Crocodile Who Snaps Chains with His Jaws!

"The engraving of Zolgar looks like the ape I operated on, and the names match," said Vasily. "I need to get to the bottom of this."

"I don't."

"Can we drive to Pomona tonight?"

"I'm exhausted."

"A big movie star like you—you must own a car."

"A Studebaker, a hundred shares of Excelsior Pictures, and a rundown mansion in Bel Air. I'm really tired."

"Damn it, Sonya, my patient is being exploited."

"Here's the deal. Ferris doesn't need me on Thursday. I'll appear outside your clinic at noon, and if you're sober, we'll go visit Zolgar."

"For his sake, I'll hold up my end of the bargain."

She surveyed Zolgar's portrait. "He obviously deserves better, to say nothing of the scientist."

"Maybe you should bring your checkbook."

#

As Sonya had anticipated, Homer thought Vasily's foray into cross-species brain surgery might make an engaging radio drama, so he asked to join the expedition. Against all odds, it was a sober and even sedate Vasily who strode out of the former sanitarium, a brick monstrosity on Loch Lomond Drive. He approached Sonya's Studebaker at a steady gait, his breath smelling only of jelly donuts, and climbed into the back seat.

Despite Homer's incipient potbelly and pasty complexion—it was hard for a white person not to acquire a tan in Southern California, but somehow he'd managed it—Sonya found him physically attractive. Over time their relationship had achieved a congenial equilibrium. Neither partner had any use for matrimony. Both periodically required total privacy and spaces to call their own (and to mess up accordingly), hence Sonya's deed to the shabby Bel Air mansion she called Medusa Manor and Homer's long-term lease on a decrepit houseboat in Marina del Rey. They regularly visited each other's sovereign domains, sleeping in yin-yang conviviality and making breakfast together the next morning—and yet their "getaway cars," as Homer put it, her Studebaker and his Oldsmobile, remained indispensable to the arrangement.

For nearly an hour, Sonya drove them east through the suburban wasteland that stretched from LA to Pomona. Vasily spent the trip jabbering about the protocols he'd devised for managing Zolgar's case. Thanks mostly to experimental drugs, he'd minimized swelling, staved off bacterial infection, and forestalled tissue rejection. By the time they reached the fairgrounds, she found herself admitting that, as irresponsible quacks go, her brother was evidently among the best.

With its tatty attractions and bracingly sordid atmosphere, Pollock and Boggle's Peripatetic Panorama put Sonya in mind of Tod Browning's Freaks, the second picture he'd made after his Dracula success. Calliope music rode the afternoon breezes. Gamey fragrances thickened the air. A single thirty-five-cent ticket admitted a customer to all the sideshows. Briefly the group patronized the Siamese twins, who were apparently the real thing, spliced together by a vivid fleshy seam, but they decided to pass up the bearded lady, the mind reader, the armless knife-thrower, and the steel-jawed crocodile, heading instead for the tent with the A-frame billboard touting the spiritual spectacle that lay beyond.

Sister Celeste Torrance

the Evangelical Wonder

presents

Brother Zolgar

the Primate Prophet

Next Show 2:00 pm

The sweet scent of musty canvas permeated the interior of the tent; Sonya spotted three empty chairs in the back row. As she and her companions settled in, the other patrons released a collective gasp. Dressed in a burlap coat and worn-out sandals, Brother Zolgar crept out from behind a curtain on all fours and swayed his way toward a blackboard suspended beside a plywood pulpit. Having never seen a live ape before, Sonya was immobilized by amazement.

Now a dainty, dimpled young woman, wearing a robe of shimmering white chiffon, appeared and stood behind the pulpit. Sister Celeste Torrance beamed extravagantly while rotating her head and trunk in an arc, as if delivering a separate, personalized smile to each and every audience member.

"Ladies and gentlemen, seekers and searchers, wanderers and wayfarers," she said in a high, breathy voice, "we have among us today a citizen of the Congo who became a prophet after being visited by an angel." She sashayed up to the gorilla and presented him with a stick of chalk. "Brother Zolgar, tell us the angel's name."

The gorilla snatched the chalk away and wrote MOIRA on the blackboard in squiggly capital letters.

"Did Moira give you the power to understand human language?"

YES.

"Did she teach you how to talk?"

APE LARYNX CAN'T MAKE HUMAN SOUNDS.

A stumpish man in a pinstripe suit pushed a canvas flap aside and entered the tent holding a vacuum-tube console trailing an electric cord. Taking a seat in the third row, he balanced the device on his knees: a radio receiver, Sonya decided, though instead of a dial it had a red push-button.

"What did Moira tell you about the origin of your species?" asked Sister Torrance.

Zolgar began to write, but his broad shoulders obscured the audience's view. He stepped away and with an open palm gestured toward the slate.

EVOLUTION.

The pinstriped man pushed the red button. A subtle spasm passed through the gorilla, roiling his fur head to toe.

"Good Lord," muttered Homer.

Zolgar's frightened gaze shifted from the incendiary word to the radio—not a receiver after all, Sonya realized, but a transmitter—and back again. Hastily he supplemented his answer.

EVOLUTION IS AN EVIL NOTION.

Several patrons applauded.

"Tell us more," said Sister Torrance.

MY ANCESTOR WAS APE WHO LIVED WITH ADAM IN EDEN.

Approving murmurs filled the tent, though none of them came from Sonya or her companions. The sheer vulgarity of Sister Torrance's act, and the electric coercion on which it turned, set her teeth on edge.

"Does anyone have a question for Brother Zolgar?" Sister Torrance's sweeping gesture encompassed the entire audience.

A young woman in a pink blouse haltingly addressed the Primate Prophet. "Exactly ten years ago, the Scopes Trial began in Dayton, Tennessee. Do you know about it?"

As Sister Torrance cleaned the slate, Zolgar cast a wary eye on the pinstriped man.

SCOPES RIGHTLY FOUND GUILTY. TAUGHT MEN ARE MONKEYS.

"What do you say to people who believe in the Darwinian theory?" asked a strapping young man in a plaid flannel shirt.

Oddly enough, Sonya had recently heard a character in an old-house thriller, The Monster Walks, featuring an allegedly homicidal chimpanzee, use that very phrase, "the Darwinian theory."

LOVE GOD'S DESIGNS, NOT DARWIN'S GUESSES.

"I have truly sinned," said Vasily.

#

As Sonya approached the Peripatetic Panorama headquarters, a rusty trailer on the far side of the fairgrounds, she wondered whether Messrs. Pollock and Boggle knew about the implanted electrode and the pinstriped man. She liked to think they were either ignorant of the Rowen brothers' modus operandi or regarded it as essential to the public service Sister Torrance was providing.

Vasily rapped on the trailer door.

"Come in!" piped up a reedy male voice.

Entering, the three Panorama patrons encountered a dwarf dressed in a tuxedo and smoking a cigarette. He greeted them with a scowl that seemed larger than his face.

"Whaddaya want?"

"We would like to see Mr. Pollock or Mr. Boggle," said Sonya.

"Lester Boggle's wife shot him last week. Didn't you read about it?"

"I hope it's not serious," said Vasily.

"His affair with the bearded lady was serious, likewise the bullet in his heart," said the dwarf. "You'll have to settle for Mr. Pollock." He turned and shouted toward the back of the trailer. "Hey, Sam! You off the can yet?"

Somebody flushed a toilet. A corpulent, broken-nosed man appeared from behind a blanket, hoisting up his trousers. Banded with saliva, a blimp of a cigar jutted from between his yellow teeth.

"Good afternoon, sir," said Sonya's brother. "I am Dr. Vasily Orlov. My colleagues and I hope you can spare a minute, as per that venerable maxim, 'The customer is always right.'"

"You want your money back?" growled Sam Pollock. "Take it up with Lester."

"I thought Mr. Boggle was dead," said Vasily.

"He is. That's what I think of your maxim."

Sonya could scarcely believe her good luck. Pollock was gripping the June issue of Photoplay, which included a six-page illustrated feature about the Woman of a Thousand Faces.

"That happens to be me on the cover," she said, pointing.

Pollock held the Photoplay cover adjacent to Sonya's face. His gaze oscillated between the full-color studio portrait of Nocturnia and the strange woman in his trailer.

"Christ, it really is you! I'm your biggest goddamn fan!"

"Then maybe we can do business," said Sonya. "I was enthralled by something I saw today, and I must have it."

"You're offerin' to buy my carnival?"

"Just one act."

"Call me Tyrone," said the dwarf. "Can I call you Sonya? Can I tell my kids I'm on a first-name basis with the She-Wolf of Paris?"

"Sure, Tyrone," said Sonya. "Let's all go camping sometime."

"Which act?" said Pollock.

"The Primate Prophet."

"He's not for sale. He's not even mine to sell. Your scheme's outta the question. Forget about it. Nothin' doin'. How much did you have in mind?"

"Five thousand dollars," said Sonya. "I have my checkbook with me."

"Jeepers." Pollock looked like a child who'd just inherited a candy store. "What does a movie star want with her own private revival meeting?"

"Zolgar is being treated cruelly," said Sonya.

"Here's the problem," said Pollock. "The two gentlemen who put the act together—"

"We know all about the Rowen brothers," said Vasily. "Matter of fact, I'm the surgeon who augmented their gorilla's brain."

"Is that so?" said Pollack. "The thing is, the Rowens pay me twenty bucks a week to exhibit Zolgar. They also cover Sister Torrance's salary."

"At twenty dollars a week, how long would you have to showcase Zolgar to make five thousand?" asked Sonya.

"I'm not good at arithmetic," said Pollock.

"Five years," said the dwarf, "and only if they worked every week."

"Of course, the Rowens would have me arrested if I simply went and sold their monkey," said Pollock.

"Ape," said Vasily.

"Tell 'em it ran away," Homer suggested.

"Yeah—to Tijuana," added Tyrone.

"Here's the other problem," said Pollock. "For me to simply throw Celeste out in the street would be unethical."

"As opposed to torturing a gorilla six times a day?" said Homer.

"Torturing?" said Pollock.

"You don't know about the red button?" said Homer.

"Red button?"

Sonya experienced a double revelation: Pollock was lying, and it didn't matter.

"While we're negotiating for Zolgar," said Vasily, "maybe we can reach a settlement with the young woman."

Pollock rested his hand on Tyrone's head as if he were a newel post. "Go get Celeste."

The dwarf disappeared, and for the next fifteen minutes Sonya, Homer, and Vasily listened patiently as Sam Pollock summarized the screenplay he'd written last winter, a horror melodrama about a traveling carnival in which all the performers were zombies.

"Tyrone typed it up. The carbon's around here somewhere. Would you like to see it?"

"Not just now, thanks," said Sonya.

"I've titled it Horror Beneath the Bigtop. Or do you prefer Charnel House Jamboree?"

"Go with your first instinct," said Sonya. "Nobody knows what a charnel house is."

Now the dwarf returned with the delicate Celeste, who radiated the disgruntled air of a bridesmaid who believed the groom should've been hers.

"Tyrone tells me I'm about to lose my job," she snorted. "Just so you'll know, Miss Nocturnia, if you manage to shut down my Zolgar act, the Rowens don't have any other work for me. This whole situation stinks to high heaven."

"Sister Torrance," said Vasily, "I could always use a second surgical assistant."

"Unless, of course, you've had formal medical training," said Sonya.

"You do surgery?" said Celeste.

"I'm the doctor who planted a human cerebral hemisphere in Zolgar," said Vasily. "I can start you at eighteen dollars a week."

"I convinced the Rowens I was an evangelical wonder," said Celeste. "I can probably convince your patients I'm a nurse."

"From your performance this afternoon," said Homer, "I would've sworn you're a genuine revival-meeting queen, another Aimee Semple McPherson."

"Look around," said Celeste. "Do you think Sam's hooey show is a friggin' church? Tell you the truth, I'm not the world's most religious person."

"You could've fooled me," said Tyrone.

"Can you tell us why the Rowens went to all this trouble?" asked Sonya.

"They say they're defending God's honor. Of course, their own honor could use a bit of polishing. They stole Zolgar from a veterinary clinic in Burbank."

"Stole him?" said Homer. "Then they can hardly question Mr. Pollock's right to sell him."

"Sister Torrance," asked Vasily, "have you any idea who owned the human brain the Rowens brought to me?"

"I certainly do," said Celeste with a fleeting smile. "You'll never guess."

"Tell us."

"Am I definitely on your payroll?"

"You'll find the work fulfilling. At the Orlov Clinic we treat epilepsy, hydrocephaly, blastomas …"

"Where will I live?"

"I have a guest cottage," said Sonya.

"Do I gotta share it with the monkey?"

"He'll get his own suite in my mansion."

"I hate to say it, but I'm not convinced the Rowens will believe Zolgar simply hied himself to Mexico," said Pollock.

"Might I ask you a favor, Sam?" Sonya pulled her checkbook from her shoulder bag. "Would you mind if I showed Horror Beneath the Bigtop to Isaac Bachman at Excelsior?"

"Would I mind?"

"If it's half as exciting as what you've described …"

"It sounds great to me, too," said Homer, "and I'm the head writer on Ticket to Tomorrow."

"Did you write the one about the nine starfish who get to be an actual constellation in the sky?" said Celeste.

"Everybody's favorite," said Homer.

"But did you write it?"

"Well, no. I thought it was maudlin."

Pollack rummaged around in a steamer trunk and, retrieving the carbon copy of his script from beneath a stack of gaudy pulp magazines, placed it in Sonya's grasp. "Of course you can show it to Mr. Bachman."

"So we have a bargain—right?"

"Done and done," said Pollock.

Sonya deposited the carbon in her bag, wrote $5,000 on the topmost check, and recorded the date. "Do I make it out to 'Sam Pollock,' 'Peripatetic Panorama,' or what?"

"My current financial institution knows me as 'Nathan W. Treet.' That's T-r-e-e-t."

"Sam likes to move his funds around," Tyrone explained. "It simplifies matters when the bank mistakenly bounces a check."

Sonya wrote, "Nathan W. Treet," then passed the check to Pollock, who folded it in half and secured it in his wallet.

"So tell me, Sister Torrance—who was the brain donor?" asked Vasily.

"That poor dead scientist the Rowens can't stand. You know, the one with the monkey theory. The Victorian chump called Darwin."

"Charles Darwin?" said Vasily. "That's crazy."

"No," said Celeste. "That's show business."