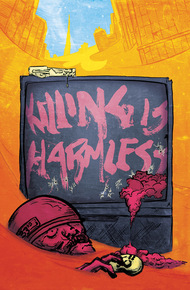

Killing is Harmless takes videogame criticism to unexplored depths, revealing the dark connection between videogame players and their characters through the third-person shooter, Spec Ops: The Line, developed by Yager and published by 2K.

Brendan Keogh effortlessly weaves long-form narrative journalism and academic criticism with references to popular culture, politics and sociology, raising questions about how we play videogames and the moral responsibilities (or lack thereof) of videogame players.

Killing is Harmless is essential reading for those who think about videogames. And for those who want to.

“It’s rare for a critic to spend this much time and energy on a single work, and even more so in the world of video games.”

–Ben Kuchera, Penny Arcade Report“It’s 169 pages of fluent, observant videogame criticism and narrative, written by the kind of person who’d throw together 50,000 words propelled only by the sheer romance for telling people about a great game.”

–Dan Golding, Crikey“A landmark book on games criticism.”

–Leigh Harris, MCV“By embracing the recurring contradiction of killing equaling fun in videogames, Spec Ops: The Line offers a stark portrait of the state of the medium; by critiquing that portrait in such intricate detail, Killing is Harmless explores what games can do to become better.”

– Edward Smith, International Business TimesThe Line starts slowly and generically enough by giving me some bits of cover and teaching me the cover controls. I have trouble with the controls at first; they are just similar enough to Gears of War to be familiar and just different enough to mess with my muscle memory.

When I say The Line is generic, I do not mean bland or unoriginal. I mean ‘generic’ in the semantic sense of ‘genre-ic’. It is a game that solidly attempts to fulfill the role and gameplay of a specific genre: the shooter. Similarly generic about the game is the use of Nolan North to voice the playable character Captain Walker. It is a running joke that Nolan North voices practically every videogame’s playable character. His use in The Line is very much intentionally generic. North is a talented voice actor, capable of a great range of different voices, but the voice he uses for Walker is the most typically North-ish, almost identical to that of Nathan Drake. Just as the game can only really examine shooters by being a shooter, the use of the most common and welcoming voice in videogames as my playable character lures me into feeling comfortable. It lets me think that I know exactly what kind of game this is, that I know what is going on. It lowers my defenses.

Even Walker’s name is generic. Walker. The one that walks. That is the role of the playable character: to be the player’s vehicle through the world and its narrative. And, all the way to his downfall, that is what Walker does: he walks. If he only ever stopped walking forward, so much carnage would be avoided. He just needs to stop walking.

Indeed, the very first landmark I walk past in the game after the initial tutorial cover is a STOP sign. Bright red, pointing right at me. STOP. Just stop. It’s foreboding. It doesn’t say “Do not enter.” It just says STOP. The choices I will make in this game are irrelevant. The only choice I can make is to play or to stop.

I ignore it. Of course I ignore it. Why wouldn’t I? I move on.

Not five steps past the stop sign, Lugo says, “What happens in Dubai, stays in Dubai.” It is the first of many quippy one-liners that the members of Delta say that don’t seem significant at all until my second game. It’s a play on a common enough saying, signifying that ‘anything goes’ in this insular experience that is entirely detached from the rest of our life. “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.” Of course, this doesn’t work out for Walker. As Konrad explains to Walker in one of the game’s possible endings, once men like them cross a line, there is no going home. It’s not simply a matter of what happens in Dubai staying in Dubai after Delta leaves and gets back to their ‘real’ lives. Rather, those who enter Dubai stay in Dubai, and those that leave Dubai are not the same people that entered it.

My squad passes an inverted US flag and some corpses of the 33rd, and walk down a highway jammed with the rusting cadavers of cars that tried to escape the sandstorms. Delta are set up as the most generic, clean-cut of videogame characters. Lugo reflects on how this wild goose chase is wasting the time of “three cold hard handsome killers like ourselves”. Perhaps continuing the commentary on the unaware playable characters of most shooters, Walker asks Lugo, “Lugo, do you ever actually hear the shit that comes out of your mouth?”

“No sir,” Lugo replies. “I do not. I find it messes with my rhythm.”

Videogames are all about finding a rhythm. The rhythm of a kill streak, of an active reload, of 8 goombas being knocked out with a kicked shell. We find a rhythm and then we lose ourselves to it. Sometimes I just ‘zone out’ playing Super Meat Boy, not even thinking about what my fingers are doing. If I realize I am not thinking, I start thinking about what I’m doing, and that is when I start to fail more, that is when I lose my rhythm. Similarly, if Lugo stopped to think about the things he says, he would lose his rhythm that allows him to unthinkingly be a “cold hard handsome killer”.

It doesn’t take long for the squad to come across the distress beacon transmitting the message and a freshly killed US soldier. The camera zooms in pretty closely on the corpse’s wide-eyed face. The death of this single US troop is meant to be shocking. Or, at least, we are meant to note that it is shocking for the characters. Walker noticeably flinches and looks away as the body collapses out of the jeep. For me, a dead body at the start of a videogame is about the least shocking thing I can think of. In retrospect, that says something about me.

Moments later, we confront the first signs of human life in Dubai. Three gunmen stand atop a bus, looking down at us, assault rifles pointed. Walker takes cover as Lugo tries to reason with them in Farsi, to convince them we are here to help. Obviously, the gunmen are suspicious (for very understandable reasons, I realise as the conflict that happened here becomes clearer as the game progresses).

Because The Line is a generic shooter, I know that we have to begin shooting things sooner or later. I have played enough similar games to know that these negotiations are going to fail. I have played enough similar games to know I am going to shoot these men.

Likewise, Walker and Adams expect the situation to go downhill. While Lugo continues to negotiate in Farsi, Adams notes the bus behind the gunmen is filled with sand, and shooting out the windows would wipe them out. To ensure I know what he is talking about, the game paints a big, red, flashing crosshair on the bus’s window, almost demanding me to shoot it. Really, this is just a tutorial segment, teaching me a way to exploit the environment that the game will afford time and again.

The lead gunman of the group, who has been listening to Lugo negotiate, looks over and sees Walker and Adams whispering. He assumes we are plotting to kill them and orders his men to open fire. Instantly, without even really thinking, I shoot at the big red crosshair and crush them under sand. What’s perhaps ironic about this scene is that we were plotting how to kill them. This conflict which precedes all the game’s conflicts happened because this is a shooter and both Walker and myself assumed there would be shooting. There just had to be. In a strange kind of confirmation bias, the game taught me how to be violent—the characters planned how to be violent—at a time when violence might not have been the only way out of the scenario. Like Neo knocking over The Oracle’s vase in The Matrix, the scene ended in violence because I knew it would end in violence. This leads into the game’s first shootout. It’s a typical shootout, mechanically no different to what you would find in any other cover-based shooter and thematically no different to what you would find in any other modern military-themed shooter. Masked, generic Arabic men with scarves over their face shout in a foreign language as they shoot at us, and we three American men just put them down as we slowly move forward from one piece of cover to the next.