Patrick Lindsey

Patrick Lindsey is a game critic currently residing in Boston. In addition to co-writing the interactive fiction game Depression Quest, he also co-hosts both the Indie MEGAcast and Bullet Points podcasts. His work has appeared in outlets such as Five out of Ten, Paste, and Unwinnable. He likes focusing on the intersection of narrative and mechanical design.

Reid McCarter

Reid McCarter is a writer and editor living and working in Toronto. He has written for sites and magazines including Kill Screen, Pixels or Death, Paste, and The Escapist. He is also editor-in-extremis for videogame site Digital Love Child and is the co-editor of SHOOTER, which you're reading right now. He tweets tweets @reidmccarter.

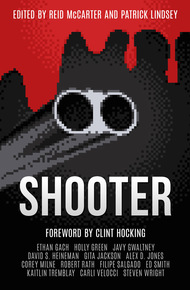

SHOOTER is an anthology of critical essays about first-person shooters. The 15 chapters explore the genre from a variety of cultural, social, political, and historical perspectives. Featuring chapters from some of the best minds in game criticism, custom hand-drawn illustrations, and a foreword by Clint Hocking, lead designer on Far Cry 2 and Splinter Cell.

"Including a foreword by Far Cry 2 designer Clint Hocking, this eclectic set of fifteen longform articles on first-person shooters and their ilk is a great chance to take a deeper cultural look at some of the best-selling and most-played games out there - from the Call Of Duty franchise to S.T.A.L.K.E.R., Borderlands, Far Cry, and many more." – Simon Carless

"When a piece of criticism grabs you by the collar and demands you take a second look at something, you know it's doing its job right."

– Nic Rowen, Destructoid"This isn't a technical book about the evolution of shooters or homages to particular games. Each essay is getting at something else, and together they become about something bigger than a genre: they're about humanity."

– Riley MacLeod, Haywire Magazine"The prime work of a critic is that of recontextualization, and the work that's on display in Shooter is top-notch in that quarter."

– Cameron Kunzelman, PasteVideogames have been around in some form or another for nearly half a century. Even so, it's only been within roughly the past two decades that the medium has gained any sort of traction in the social consciousness of the general public and grown beyond its traditional place as a niche hobby. Shooters have been at the forefront of this public awakening, though admittedly the increased attention hasn't always been positive. On the contrary—more often than not, when videogames in general and shooters in particular make their way onto the pages of our newspapers, it's likely because they've been elected the most convenient scapegoat for a given crisis. In 1999, political figures, news outlets, and parent-led advocacy groups turned their collective attention to DOOM, citing it as the main catalyst for the massacre at Columbine High School. More than 10 years later, media outlets once again took up arms against shooters, blaming Call of Duty for inciting Anders Breivik to kill over 70 people in Norway. For the majority of the non-gaming public, incidents such as these are the only reference point they have to shooters—or even games as a whole. All the same, despite their ostensibly simplistic design and often questionable subject matter, shooters are a fascinating genre. They serve as a double-sided mirror through which we can view not just the history of a medium's development, but also how its influence radiates outward into popular culture. The development history of the genre is fascinating in its own right, but these games also give us a unique way to interact with our own history, social attitudes, and personal experiences. In its own small way, SHOOTER is meant to serve as a starting point for readers interested in this. If videogames are to continue to hold an important place in our culture, it's necessary for critics—writers willing to seriously examine games not as products, but as works of art and entertainment—to unpack their meaning. The diversity of approaches taken by this book's writers should, we hope, show just how rich a subject the shooter is. This genre plays an outsized role in videogames (for players and outside observers alike) and, by collecting a series of articles centred on some of its most noteworthy titles, SHOOTER hopes to offer an outline of this subject's critical depth. In David S. Heineman's "Shooting Things in Public: Battle Garegga and the Arc of a Genre," the reader can trace the shooter's transition from a venue for skill-testing public performances to a type of game best played alone. In Steven Wright's "The Joys of Projectiles: What We've Forgotten About DOOM," we see the genre move from fantastic and imaginative to grounded, "realistic" settings. In "Action, Death, and Catharsis: Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare," Reid McCarter explains that as shooters have grown in popularity, the focus has, at least ostensibly, moved away from mindless arcade entertainment to a reflection of (and target for) our own cultural and social hangups. In the history of the medium, we can also see the history of our popular culture. In these essays the reader can watch not only how the mainstream videogame has changed in tone—shifting from arcade cartoons full of spaceships and demons to a more sober setting affording players the chance to engage with real cultural issues—but also the way in which that transition has been reflected in gameplay. Javy Gwaltney bridges this developmental paradigm shift in "Gilded Splinters: BJ Blaskowicz and The New Order," drawing a parallel between the historical time lapse presented by the game's narrative and the similar passage of real-world time. Here we see that just as the world around us changes in the face of given social and cultural factors, so too does the landscape of videogames. In fact, Gwaltney's parallel with epic poetry, particularly Beowulf, hints that the connection between genre development and sociocultural change may actually be more closely linked than many of us realize. More than its own history, however, shooters have become a go-to means of contextualizing and re-presenting significant events from our own historic past. Corey Milne points a finger at Western developers in "Brothers in Arms: Hell's Highway and German Representation During World War II" for perpetuating the simplistic "good vs. evil" narrative so common among Allied countries during World War II and in the decades since. Games' rigid adherence to these common tropes, which narratively and thematically blur the line between Nazi SS officer and standard German infantryman, robs us of the perspective we as a global community have gained in the years since the war's end. In a similar way, Carli Velocci's experience with the "realistic" WWII shooter ("The Disempowerment Fantasy of Red Orchestra 2: Rising Storm") demonstrates how a shooter's mechanics can be used to subvert our typical understanding of Second World War battlefield heroics by focusing instead on the helplessness of individual soldiers. Aside from the larger cultural landscape, videogames also offer arenas for a more individualized form of analysis. Both Holly Green in "Fallout 3: If You Can't Join 'Em, Beat 'Em" and Kaitlin Tremblay in "Perfect Dark: A Bundle of Bones" outline their own journeys of personal discovery from within the context of shooters. The interactivity of games and the personal connection between player and avatar make the medium uniquely suited to this type of exploration. We see this, too, in Patrick Lindsey's "Far Cry 2 and the Dirty Mirror," which discusses how the close proximity between audience and game character can be used to comment on the medium's—and the shooter player's—propensity for violence. What's more, Gita Jackson outlines (in "My Brother, Counter-Strike, and Me") how a given shooter can function not only as a bridge connecting two siblings as they grow older, but also as a metaphor for the unique dynamic of their relationship; in a way, Jackson is bringing us into her relationship with her brother by presenting it in terms we, as shooter players, can identify with. Work like this brings a special kind of specificity to the universality of games. To understand the shooter in design terms, it's important to first understand the importance the power fantasy plays in the medium's interconnected storytelling and mechanical systems. Ed Smith's "Truth Versus Propagana: Fighting Through the Haze" examines the manner by which gameplay mechanics and structuring can be used to comment on a player's willingness to engage in acts of violence. Filipe Salgado's "Kane & Lynch 2: Hell is Other People" discusses how successfully players can be brought into the world of hardened, sociopathically violent criminals through gameplay and audiovisual aesthetic. Ethan Gach unpacks how this process can fall apart by looking at the lack of success a massively popular series has had in marrying its storytelling with gameplay in "Paths of Contact: Narrative Friction in Gears of War." Alex D. Jones's examination of S.T.A.L.K.E.R: Call of Pripyat, a game set within the irradiated wastes of an apocalyptic, post-Soviet Ukraine ("To Conquer Pripyat"), explores the relationship between power and vulnerability from within the context of a videogame whose digital landscape is as opposed to the player as any heavily-armed enemy soldier. And lastly, Robert Rath's "The Lurking Fear: Firearms in Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth" looks at how a videogame willing to treat the gun as a powerful weapon rather than a useful tool can change our understanding of shooter conventions and, quite possibly, firearms in general. All of these essays, in their own way, grapple with the subtexts inherent to games from a genre most often thought to contain nothing more than meaningless exercises in violence. They challenge our understanding of familiar conventions and, we hope, demonstrate the ramifications that the shooter's immense popularity has on individual thought and our culture in general. This seems an ideal area of game criticism to begin with because with the shooter we see a kind of distillation of videogames as a whole. In them everything is bigger, exaggerated. The player who typically identifies with the avatar they control looks through their very eyes here; the weapons used by game characters are clutched by hands meant to stand in for their own—the violence that so often typifies the medium is emphasized in this genre more than any other. The shooter, in other words, serves as a kind of microcosm for the medium as a whole. Criticism of some of its most influential games is the kind of criticism that serves any videogame player interested in delving deeper into their favourite titles or the medum's influence on the modern world.