Mark, who is still afraid of the monster under his bed, grew up on a steady diet of Spider-Man and Tales from the Crypt comic books. A self-confessed book nerd, he has been writing since he was thirteen and discovered his mother's Underwood typewriter collecting dust in a closet. His first short story appeared in print in 1992, the same year he started working in the book industry. He has published more than twenty-five books of horror, thrillers and fiction (I, Death, One Hand Screaming, A Canadian Werewolf in New York, Hex and the City), paranormal non-fiction (Haunted Hospitals, Tomes of Terror, Creepy Capital) and anthologies (Campus Chills, Feel the Fear, Obsessions).

Mark lives in Waterloo, Ontario and can be found at www.markleslie.ca, wandering awestruck through bookstores and libraries, and searching out craft breweries and eerie haunted locales.

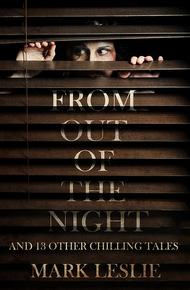

Beware those things that creep up on us from out of the night!

Although technology dominates much of our modern world, there still exist things that have been with us since we huddled in caves around brightly burning fires and avoided ominous shadows.

Strange beings of the night become frighteningly real to us even now as we venture two decades into the twenty-first century. We have electricity, the internet, and powerful devices that can connect us with the world that we can carry in our pockets or hold in our hands. But despite this, unknown things are still out there going bump in the night; a night where our dreams so easily morph into nightmares.

Scientifically, we have grown out of the dark ages, but our fears will forever remain there jumping at shadows outside the cave.

And perhaps for good reason . . .

Join author Mark Leslie as he takes you on an intimate walk through fourteen different tales that sink directly into the shadows, those after-dark moments, when all rationality disappears, and our primitive fears take hold.

Mark also appears in this bundle as a writer of scary tales. He compiled Out of the Night from his horror short stories or, as he calls them, "chilling tales." Mark knows chilling and scary and thrilling. What else would you expect from a man who travels with a skeleton riding shotgun? (Well, maybe one more thing: This volume is also exclusive. That's Mark for you. Generous to a fault. Which is not scary.) – Kristine Kathryn Rusch

"Mark Leslie has a knack for creating chills. His fiction is like bare cones caressing the skin; creating a shiver here, a delicious northerly tickle there. Beware dark corners, empty alley ways, lonely streets, the quiet room when Mark beckons for you to take his literary hand in yours."

– Carol Weeks, author of Water’s Crossing"Mark Leslie's horror is reminiscent of the old-time storytellers, those guys who cared about plot, and were pretty good at building a creepy tale. If there's a dark corner, Leslie will draw you to it, even against your will."

– Nancy Kilpatrick, author of Revenge of the Vampir King, Bloodlover, and Evolve: Vampire Stories of the New Undead"Prepare to be haunted by a master of suspense. Leslie paints his characters with compassion, then sends a chill down the spine. Highly recommended."

– Julie E. Czerneda, author of Survival, Hidden in Sight, and Reap the Wild WindOpening From "Erratic Cycles"

Charles Dean Webster, attorney at law, sat very still in his '89 Toyota Tercel, frustrated over his predicament. Something—he had no idea what—had happened to his car. First there had been smoking and hissing and then the car had stopped running. That was the extent of his knowledge about what was wrong with his car. He was a lawyer, not a mechanic.

Dammit Jim, I'm a lawyer, not a mechanic.

He looked at his watch, taking his eyes off of the forest for only a very short time. It was a quarter past nine. As he lifted his head to look down the barren stretch of Highway 144, he caught the glare of the setting sun in his rearview mirror.

"Damn!"

He slammed a fist against the dash and then sat back once more and stared out the bug splattered windshield at the deserted highway.

Why me? he asked, and was quick to find an answer.

Why not you?

This was going to be your big case, your first major success, your big break. This was going to be the case that not only brought you a handsome sum but spread your name across the country. After winning this one, you were finally going to be someone.

So why not you? If you continue to believe such stupid glorified dreams, then why not you? Face the facts, schmuck: This is just another case.

And, being just another case, it had been nothing but a pain in the ass from day one. Getting stranded on a lonely highway somewhere between Sudbury and Timmins was just par for the course.

He looked at his watch again, but only a minute had passed since he'd last checked it. His eyes quickly returned to the wall of forest which ran never-ending along both sides of the highway. He couldn't shake the feeling that something was watching him from the forest.

No, not something, he corrected himself.

The Bush People.

He shuddered at that thought and considered turning on the radio to help alleviate his mood; but he was afraid that it would kill the battery. And he needed the battery in order for the hazard lights to keep working? Didn't he?

Dammit, it always came back to that, didn't it?

He hated the fact that he knew nothing much about how a car worked. But that had been his father's profession, not his.

When he was still young—very young—he'd watched his father closely. Anthony Webster would come home from the garage and spend as long as twenty minutes washing his hands and never really getting them clean. The tracks of his fingerprints were a permanent resting place for the grease and oil of his livelihood. Then, after supper, he would sit down in the living room with a beer in one hand and a remote in the other and grumble about inflation, taxes and the latest antics of the Toronto Maple Leafs. And the next day the cycle would repeat: Work, a vain attempt to wash away the residue of that work, and when that failed, a cleansing of the soul with beer and bitching.

Charles loved and respected his father who had never been anything but reliable and supportive. He'd always provided his only son with everything he could afford to give him and only once had he raised a hand to him—but in retrospect, Charles had deserved that quick slap after having verbally assaulted his mother in a typical teenager/mother argument. Anthony Webster was as close to the perfect father as any man could be.

But the last thing that Charles wanted was to be like him. He could never lead such a mundane existence. Charles wanted more than just money and a career. He wanted an exciting and fulfilling lifestyle. He didn't want his father's life of broken car after broken car—every day slaving over someone else's troubles and ultimately getting nowhere in life.

No, that wasn't for Charles. That wasn't what he wanted at all. He yearned to be a lawyer, to experience the lifestyle portrayed in the L.A. Law television series he'd loved so much; so he reached for it.

But he never got it.

Every case he took on held the promise of being the case which would move him up. But they never did. Instead, he slaved day after day over someone else's troubles, someone else's broken life, never moving up.

He ended up living the very lifestyle he had dreaded: His father's. Only, Charles lacked many of the things that his father had, including the knowledge of how a car worked.

Charles had been too engrossed in his own personal dreams to bother hanging around with his father and learning a few essential details about his trade.

And because of it, he was stranded.

Caught in the very trap he had attempted to avoid.

So it always did come down to that, didn't it? Running away from something only brought it down on you even worse.

His cellular phone was rendered useless by the remote location he was stranded in. He didn't even know how far it was to the next town, or at least to the next pay phone. If he knew, he might consider walking. It would be far better than sitting around waiting for another car to drive by.

Although it had only been fifteen minutes since he saw any traffic, he was afraid that no one else would drive by. He'd never driven out of the concrete corridor before and had no idea of what to expect. Besides, even if someone stopped, would they even bother helping him if they knew who he was?

If only he could get to a phone and make one toll free call to the CAA.

Charles smirked and looked at his watch again without reading it. With his luck, his CAA membership would probably have run out, or for some stupid reason they didn't cover this area. Or perhaps the nearby CAA was run by one of the local groups that despised him. Wouldn't that be a cute confrontation? He wouldn't be surprised if any of these things happened—everything else had gone wrong so far.

It had started out as a simple case. His client, a Toronto-based company called Durban Lumber, had purchased a large chunk of land near Timmins for their logging operations. The only issue when Charles had picked up the case was a local band of Indians claiming traditional rights to the land. But Durban Lumber had purchased the land from the municipality and held legal ownership. It was a straightforward matter of Charles walking in, going through the motions, flashing the ownership papers, quoting a sample of similar past cases in which the defendant was triumphant, and hopefully settling it out of court.

Then a new development changed things. The native lawyers uncovered an old, weathered copy of a document that the municipality had signed with the native leaders, recognizing the land as traditionally belonging to them. Because of a fire over two decades earlier at city hall, the municipality's copy of that document had been destroyed and forgotten.

And so the simple case had turned ugly. Durban Lumber was pressing the municipality from one side while the Indians were pressing them from another. The media had eaten the story up, of course, in the popular story of big business stepping all over the little guy.

The more sour the case turned, the more difficult it was for Charles to obtain the upper hand. The stress mounted, the tension increased, and it began to get more than sour, more than ugly.

On his last visit to Timmins, a group of environmentalists and Indians greeted his plane at the airport with catcalls, rotten fruit and stones. Charles, the representative of the big bully, became the object of their hatred and anger. They all wanted a piece of him.

Things got so bad that instead of flying in to his next meeting in Timmins, Charles opted to drive. Not only would he arrive in an unexpected manner and hopefully undetected, but he could use the six or so hours that it would take him to get there to relax and sort things out.

It would be the first time he was alone in over seven years. Truly alone—without work and booze, his longtime companions.

After finishing a gruelling law school program, Charles had launched straight into his career. He started at the bottom, as most lawyers do, and had remained there ever since. He never once attributed his dire position to burn-out, but instead kept driving himself harder and harder, waiting for that one case.

At least in school when he botched a test or flunked a paper, he had the chance of redeeming himself with another test or another paper before the final grades came out. But his career, he discovered, didn't work that way. Mistakes stayed on his record, without the possibility of being wiped out by future successes. There was no chance for redemption—there was only one thing. Plugging on.

So Charles had jumped from a life of study, work, party, sleep, to a life of work, research and more work. There were no study weeks or spring breaks where one could relax and then use the time to catch up on all the areas one had fallen behind in. There were no getaway weekends like there had been in school.

This was a career. This was life. This was not at all what Charles had expected or hoped for.

The only way he could cope was using a method he had learned by watching his father. He coped with the Webster method of bitching and booze. That soon became part of his daily ritual.

Years ago, he had lived for the weekends and the promises that once school was finished he would be able to get on with living, with life, with being a free man in a free world. It wasn't long before he discovered that there was no such thing as freedom. There was no such thing as just living.

The barrage of cliches which his father spewed forth daily about the shit that life dealt an honest man were all coming true. Charles found himself not only repeating those same old tired clichés about life, but actually believing them.

Charles had discovered one night in the midst of an alcoholic haze that the cycle his life had taken was no better than his father's. Work like a bastard, the come home and drink like one. Only, his father also had a wife and a son. All that Charles had was work and booze.

It had become time to re-examine his life.

That was why this drive, this pilgrimage to Timmins, was supposed to be just the thing that Charles needed. It would be his way of being alone, without the work, without the booze. Just Charles and his thoughts. Six hours to finally reflect on what his life meant to him other than in the terms of a drunken man's armchair philosophy.

There was only quiet thought and gentle reflection as his car left the sprawling fringes of the city, headed north on Highway 400.

And then, several hours later, the car—the very means of his pilgrimage—broke down.

And Charles was alone.

In the middle of nowhere.

This newest development brought to him the real reason he had never let himself be alone for all those years.

Being alone scared the bejesus out of him.

He was surrounded on all sides, it seemed, by the thick foliage of the Northern Ontario wilderness. Wilderness that grew darker as the sun crept down somewhere behind the distant hills.

Wilderness that threatened to take him back to when he was ten and camping with his parents at Algonquin Provincial Park.

Back to the last time he had really felt alone.

Back to the time when he had first learned of The Bush People.

"No," he whispered, and it all came back to him in a sudden rush, as if the nineteen years between today and that dreadful evening had never happened at all.