David Gerrold's work is famous around the world. His novels and stories have been translated into more than a dozen languages. His TV scripts are estimated to have been seen by more than a billion viewers. He has worked on a dozen different TV series, including Star Trek, Land of the Lost, Twilight Zone, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Babylon 5, and Sliders. He is the author of Star Trek's most popular episode "The Trouble With Tribbles."

Many of his novels are classics of the science fiction genre, including The Man Who Folded Himself, the ultimate time travel story, and When HARLIE Was One, considered one of the most thoughtful tales of artificial intelligence ever written. His stunning novels on ecological invasion (A Matter For Men, A Day For Damnation, A Rage For Revenge, and A Season For Slaughter) have all been best sellers with a devoted fan following. His young adult series, The Dingilliad (Jumping Off The Planet, Bouncing Off The Moon, Leaping To the Stars), traces the healing journey of a troubled family from Earth to a far-flung colony on another world.

A ten-time Hugo and Nebula award nominee, David Gerrold is also a recipient of the Skylark Award for Excellence in Imaginative Fiction, the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Horror, the Forrest J. Ackerman lifetime achievement award, and was the 2022 recipient of the Heinlein Award. He was a Guest of Honor at the 2015 World Science Fiction Convention and emceed the Hugo Award ceremony.

In 1995, Gerrold shared the adventure of how he adopted his son in The Martian Child, a semi-autobiographical tale of a science fiction writer who adopts a little boy, only to discover he might be a Martian. The Martian Child won the science fiction triple crown: the Hugo, the Nebula, and the Locus Poll. It was the basis for the 2007 film "Martian Child" starring John Cusack and Amanda Peet.

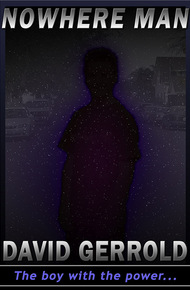

A socially maladroit teenager invents a way to become a time-slicing superhero and uses his new powers to extract an exquisite revenge on his junior high school tormentor — and in the process learns a few lessons for himself as well. This is a delicious evocation of adolescent geekery, written by a recovering adolescent geek.

"This is an enjoyable read. C'mon, who hasn't wanted to give a bully the ultimate taste of his own medicine? But Gerrold doesn't take the easy way out and just make it a tale of revenge. There are moral issues to be unraveled and they are dealt with in thoughtful, subtle ways without any shoving of the author's opinions down the reader's throat."

– Amazon review"A wonderful story about family. The ups and downs and the unexpected. Filled with varied and beautiful characters, those uninvited relatives of yours who always show up at Thanksgiving dinner."

– Amazon review"Nowhere Man" is longer, deeper, and more along the lines of the modern super-hero. What defines a super hero? What makes a person want to be one? And what if the person trying to be one entertains this kind of question, and really thinks about whether it is the right thing to do? Its main character has the requisite attributes - he is smart, he has had a broken childhood, and he has enemies who are out to destroy him. And he has a friend who has amazing technical skills and who asks the right questions And the technology, while amazing, and presented in a way that makes it all work, is NOT the focus of the story - it is just the pivot that allows it all to work. "With technology X, Y becomes possible. What else can it be used for? Am I really the right person to have that at my fingertips? If not who, if anyone, is? Wait a second - Y implies Z! Holy cow, this is more complex than I thought at first!" is the purpose of the tech, at least as much as it is the maguffin that allows the character to become a super hero. It not only allows the characters to think it through, it FORCES them to. And thereby hangs the tale. And I loved the punch line."

– Amazon reviewHe was a short kid and aggressive. He played to the crowd and they encouraged him. One bully, six or seven enablers. Familiar social dynamic. I'd read about it. Now I was experiencing it first hand. I was the geek, the nerd, the kid who knew how many zeroes in a googol and what Pascal was wagering and why Zeno never caught the tortoise. I read a book a day, always had one under my arm, never one with a yellow-and-black cover. He made fun of my reading. Selfish genes. "Your nose is the most selfish set of genes. Look how big it is." Disturbed universes. "Trying to figure out where you fit in?" How to play fairy chess. Don't ask where he went with that one.

One day, I didn't plan it, it just happened. I had a hardcover copy of The Annotated Alice, by Lewis Carroll (pen name for mathematician Charles Dodgson), with commentary by Martin Gardner. With Tenniel's original illustrations, of course. Very big book. Very heavy. Peterik said something, I don't remember what, something stupider than usual, like "only fairies read fairy tales"—and without thinking, without conscious volition, the book came up in both my hands, came up fast, came swinging around hard and swift and slammed into his face with such impact I felt his nose go crunch, and then he went flapping backward, slamming loud into the steel lockers behind him, blood spraying, his hands flying to his face, eyes wide with surprise and shock, because this wasn't supposed to be happening, and I didn't know who was screaming, but there was a lot of noise, and I was in the center of it all, a crowd, and I was pushing Peterik up against the wall and hollering into his face, "Just shut up! Shut up! Shut up! Shut up! Just shut up already!"