David Niall Wilson is a USA Today bestselling, multiple Bram Stoker Award-winning author of more than forty novels and collections. He is a former president of the Horror Writers Association and CEO and founder of Crossroad Press Publishing. His novels include This is My Blood, Deep Blue, and Many More. His most recent published works are the collection The Devil's in the Flaws & Other Dark Truths, and the historical fantasy novel Jurassic Ark – a retelling of the Noah's Ark story… with dinosaurs. David lives in way-out-yonder NC with his wife Patricia and an army of pets.

David is a USA Today bestselling author, multiple Bram Stoker Award Winner, ex president of the HWA and CEO of Crossroad Press Publishing.

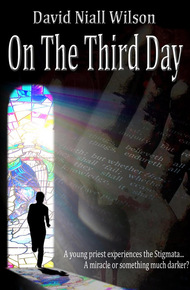

Father Darren Prescott is a seeker of truth. He works for The Vatican, but his real work is within his own mind and heart; Father Prescott hunts miracles. Father Thomas is a young priest with a quiet congregation that worships at San Marcos by the Sea, a small cathedral outside San Valencez, California. One Easter Father Thomas' Mass is interrupted by something he cannot explain – something powerful that shakes his world, and that of his congregation.

Father Thomas experiences the Stigmata.

On The Third Day is the story of Father Thomas and his search for answers. He turns to the church, and his immediate superior, Bishop Michaels, for support and assistance and is shocked to find that not all priests seek miracles. Some are comfortable with the status quo and vicious in their defense of it. Bishop Michaels is battling his own demons, not the least of which is a barely controlled love of alcohol.

Despite the distaste it engenders, Bishop Michaels attends Easter Mass the year after the first "incident." He comes armed with an attitude of furious disbelief, and a video camera. When Father Thomas not only repeats the previous year's experience, but with much greater intensity, collapsing across the altar and causing a near riot, the Bishop escapes with his camera, and his sanity, and makes calls of his own. He still does not believe, but now he feels he needs a greater power than his own to prove his disbelief, even to himself.

At the request of Bishop Michaels' superior, and his own mentor, Cardinal O'Brien, Father Prescott arrives and begins his investigation with a third Easter Mass looming. The Bishop is determined that Father Thomas be proven a charlatan and a fraud. Father Thomas is frightened for his life, and for his faith, and only wants answers. Father Prescott? He wants the miracle he's waited his entire life to overcome, to make up for what he considers past failings of his own.

What all three men find is the powerful, thrilling conclusion to On The Third Day, an experience that draws them together and pushes them apart in ways they never could have imagined. The answers are there, but some answers are too difficult to bear.

On the Third Day is one of my favorites among my own novels. It is the story of three men, faced with something beyond their understanding. As events unfold, they must decide whether to embrace the unknown, reject it, or risk their very souls to stop it… – David Niall Wilson

"I absolutely love the ending of this novel, or I should say, the endings. The characters grow and develop, and the author leaves just enough to the imagination without coming out and telling us what to think. As far as I'm concerned, everything rises for me in David Niall Wilson's On the Third Day."

–John B. Rosenman – Author of The Merry-Go-Round ManThe moon hung high in the sky and lit the empty streets with a white, hazy glow. The radiance was painful to Father Prescott's eyes, so brilliant that it cut through his senses and prevented focus on anything but the dirt of the street before him and a brighter light ahead.

He stumbled forward, though the sensation was of floating, not walking. The street was longer than he remembered, longer than it should be. He felt the weight of their eyes. They stood in doorways, between the homes, in the windows of stables and on the steps of the small adobe schoolhouse.

They followed him with their collective, accusing gaze. Every face was chiseled into a frown of disapproval, or of hatred. They stared at him like the liberated characters in an ancient painting of loss or damnation. They stared at him and he moved on, fighting to look away from their bitter faces, only to face them again in whatever direction he turned.

Ahead the light grew in intensity until it shone like a small sun, or a captured star. It sparked from the base of the chapel, leaped brightly to the sky and washed away the encroaching figures. Father Prescott wanted to hurry forward. He wanted to move into that brighter light, away from the eyes and the stares and the ancient pain that dogged his steps, but his progress was not his own to control.

As he drew nearer, he saw the statue. It pulsed like neon, or white hot metal, molded into the form of a man. Rays of light slashed from a gash in the side of the figure's skull. Something beautiful and overpowering poured from that small hole and Father Prescott wanted to drop to his knees before it, but he couldn't. He was held, prevented from drawing too near to the statue itself; prevented from escaping those who closed in now on all sides.

Shadow forms, their features clear, but their bodies obscured, melted into the light. He had the impression that they were pressing their features into the exterior of that light, pressing inward but unable to penetrate the glow.

He tried to cry out, tried to call to them, but he had no voice. He tried to raise a hand to his lips, but found that he couldn't move his limbs, except in that inexorable march forward.

He came at last to a point in the road parallel with the leading edge of the chapel. The light surrounded him on all sides, and there was a SNAP of energy. He stood within the light, firmly rooted on the ground and able to walk.

The statue gleamed and glittered, flickering now with multi-colored beams of light. The radiance still emanated from the gash in the figure's head. Father Prescott drew closer, and knelt in the hard packed dirt of the street. The eyes of the statue glared at him in dead, unfeeling anguish.

He noticed, a leather thong had been hung about the throat beneath that glowing head, and from this a pouch dangled. There was no radiance where the pouch touched - it was the single shadowed thing, and Father Prescott recognized it with a gasp.

It was not possible, he knew. This pouch could not be hanging here, and it was so long ago that any of this had happened and yet...

He reached out gently and tried to cup the leather bag in his fingers. It was slick and rubbery, and where he touched it, it grew damp. Frowning, Father Prescott pulled the thing away from the throat of the beautiful, glowing statue, but as he did so, something dripped from the interior of the bag onto his fingers, and from there to the ground at his feet.

He jerked his hand back, but it was too late. The sack began to leak, slowly at first, and then in a steady stream that poured over the white figure, washed down the statue's body and leaked into Father Prescott's skin. It spread rapidly upward, like a coffee-stain on paper leaking from the center outward until the entire statue grew dark - all but that hole in the side of its head. Where the dagger should be. Where the light poured out.

Father Prescott cried out and reached toward that light, tried to catch it in the palm of his hand, and failed. The brilliant illumination filtered through his fingers and splintered, fragmenting in all directions and then - very suddenly - went dark.

Father Prescott sat bolt upright on his cot. His skin was clammy and the sheets clung to him damply. His entire frame shook in the aftermath of the dream - vision?

It was still dark, hours before the sun would peek over the jungle and slip in his window. He drew the rough blanket at his feet back over himself, rolled into a ball, and pressed his back solidly into the stone wall of the room.

There was a rustle in the back of his mind. Something unfolded that was as familiar as his own voice, but spoken in another's. It echoed through his mind, as he lay shivering and waiting for the dawn.

Just four words.

"I believe in God."

The late afternoon sun filtered through the heavy blinds of Bishop Michaels' office, striped the walls and angled just over the heads of the two men seated on either side of the ornate mahogany desk. Tapestries hung on the wall, and the deep pile carpet was thick and soft. The wooden furniture was polished to a high gloss and the sunlight gave each surface the aspect of mellow, glowing flame. Nothing in the office was new. It whispered of ancient times, and power.

Crystal goblets surrounded a carafe that rested on a sumptuous buffet along one wall. The leather of both chairs creaked with each slight motion, and the air hung thick with silence.

Bishop Anthony Michaels sat in his dark, comfortable chair, and regarded the young priest across the desk from him over steepled fingers. The Bishop was the epitome of decorum. He had light blue eyes and a ruggedly handsome face. His hair was dark, graying at the temples – a look that was very distinguished when taken in conjunction with the carefully pressed vestments and the manicured nails. No hair was out of place. No crease or fold of material was out of order. Ordered, in fact, was the word to describe it all, ordered and proper. Immaculate.

On the desk before him sat an array of documents. Some were clipped from newspapers, others were photocopies and faxes, and all were arrayed like a silent army readying itself for the attack. The Bishop didn't look at them, but the tips of his fingers rested on the papers firmly.

Seated across from him, Father Quentin Thomas leaned in toward the Bishop's desk. He had tousled brown hair, matching eyes, and a trim, athletic build. He was not as "immaculate" as the Bishop, but perhaps a bit more honest. His eyes had a dark, haunted aspect that spoke of weariness beyond his thirty-four years.

"So," Bishop Michaels said at last, "what you are asking me to believe, in essence, is that you have experienced The Stigmata."

It wasn't a question, but a statement, as though the older man were gathering his thoughts.

Father Thomas replied, his voice quiet and strained.

"I'm not sure what I'm asking you to believe. I'm not even sure what I believe."

"There is certainly no doubt what these — people — believe." the Bishop replied, flipping the ordered papers into a jumbled mess with a quick slash of one hand. "People are easily manipulated, Quentin, as I'm sure you have come to know in your own right. The question is, to what are they being led?"

Father Thomas didn't glance at the papers. He knew well enough what they were. Letters to the Editor. Headlines from "The Rooftop," a local tabloid newspaper. Faxes from Quentin's own parishioners, and from The Vatican, and a small paper clipped pile of requests from the local television station. All of them wanted the same thing. Answers.

Bishop Michaels slowly swiveled his chair and gazed out the large, curtained window into the blue sky beyond. He rubbed the fingers of his left hand along the bridge of his nose, and then curled them under his chin. He remained that way for a few moments, and then he spoke.

"I have been a part of the church since I was a young man, Quentin. I have seen a lot of things over those years, and borne witness to a great many – experiences — that I can neither explain, nor understand."

Father Thomas sat forward expectantly, hanging on the Bishop's words. His hands trembled.

Then, without warning, Bishop Michaels spun back to face Father Thomas, slammed his hands down onto the desk and scowled at the younger priest.

"I have never heard anything like this."

He hesitated to let his words sink in. His expression slipped from its austere, almost fatherly aspect to an expression of deep disdain. He continued, biting off each sentence as if he was having a hard time passing the words.

"Your hands itched. You felt something trickle down your forehead in the heat of Easter Mass. You had a stitch in your side – and your feet hurt. Do I really need to tell you, Father Thomas, that these hardly constitute a miracle? You'd be hard pressed to find a priest in Mother Church who has not experienced each and every one of these symptoms during a Mass."

Father Thomas sat back as if he'd been slapped. His eyes were wide in shock, and his mouth fell open, though it took him several attempts to form words.

"Surely," he said at last, "you don't believe I would make something like this up? I know you heard what I said. I did not have itchy palms; I bled in front of my congregation. It ran down my arms – my face."

He fell silent for a few moments, and then he went on, the tone of his voice far away and bitter. He choked back anger – or tears – but when he spoke, it was controlled.

"I came to you for help."

Bishop Michaels' countenance remained icy, but he leaned forward over his desk. His hands gripped the edge of the wooden surface so tightly his knuckles were white spots of tension.

"Then I will grant you that help," he replied. "Make no mistake; I will put this nonsense to rest."

Father Thomas sat still as stone. His face was trapped halfway between confused anger and hope. He had never seen the Bishop so angry, never seen him lose his calm demeanor, even for a moment. He didn't recognize the man facing him across the desk, but he very much wanted to be able to trust him.

Bishop Michaels caught that glimmer of hope, and stomped on it quickly and viciously.

"Don't mistake me, Father Thomas, I see through you. I don't know how you did what you did, or why. I don't know what you think you saw or felt, or what you sold to those appointed to your care, nor does it concern me. If I had the slightest inkling that you had experienced a miracle that inkling died when you told me, not more than a few minutes ago, that you don't even know what you believe.

"I know that there is something to this, but I know equally well that it is not a miracle from God. Miracles, in this day and age, are rare, and very precious. I will not have you making a mockery of them in a parish under my control.

"I also have no idea what we are going to do about these," he swiped his hand through the pile of papers, and the frustration behind his anger shone through clearly.

Father Thomas remained rigid, as if all flexibility had been lost to his limbs, but he managed to respond, and he managed to do so in a clear, level voice.

"It is nearly Easter, Excellency," he said simply. "All that I have asked of you is that you attend, and, if something like what occurred a year ago should return to me, that you should see, and advise me."

The Bishop smiled then, but it was not a pleasant expression. He pushed off from his desk, fell back into the heavy leather of his chair, and laced his fingers together, holding them against his chest.

"And what is it that I will see, Quentin?" he asked smugly. "Will there be lots of blood? Will I hear angel choruses in the background? Will there be souvenir programs handed out at the door, do you think, or will I have to purchase that? What would be the price, I wonder? Will the walls tremble? Will I get to be on national television and cry 'Praise Jesus' like some white-suited flame-tongued televangelist?"

The sarcasm hung in the air like a bitter cloud.

Michaels hesitated, just for a second, and then said, "I will be there. Count on it."

Father Thomas stared at the Bishop for a moment of unbelieving silence, and then lowered his head. He nodded slowly and turned, his shoulders bowed. He had come expecting something; he didn't know what it had been, but not this. The Bishop's reaction had shocked him to his core. He exited without reply, leaving the heavy wooden doors open behind him.

Bishop Michaels watched the doorway until all trace of Father Thomas disappeared, and the soft brush of robes and vestments ceased to echo. The afternoon had grown late, and the light that streamed in through the windows had fallen away. The shadows lengthened slowly, stretching out from all corners of the room and following the light.

On the edge of the old wooden desk, the Bishop's grip tightened again. His nails threatened to dig into to the polished surface, and his hands trembled so powerfully that the shivers ran up his arm and shook him back to his senses. Almost absently, he reached out and gathered the scattered papers back into a neat stack.

He stared at the doorway where Father Thomas had disappeared and fought back the anger that threatened to boil out of control. He didn't glance down at his desk, because there were loose objects on that surface, and he didn't trust himself not to throw them. There were beautiful, ancient things surrounding him, on the desk, the shelves, hanging from the walls, and he was on the verge of devastating it all, rushing around the room to smash the Tiffany lamp into an ancient Sumerian vase, or to yank the hand-woven rug from beneath the table that held his cut-crystal.

When he had slowed his breathing enough to trust his hands, he released the desk and reached to the bottom right hand drawer. There were two tumblers there, and a small flask. He pulled one tumbler and the flask free, and poured two fingers of amber liquid. He stared at it, frowned, and then tipped the flask again, doubling it.

When the heat of the brandy began to seep through his nerves and calm him, he poured again, and reached across the now shadowed surface of his desk for the ornate black phone.

On a nightstand across the world, another phone rang. The shrill sound drove itself through the darkness and snatched the room's occupant from the warm, comfortable arms of sleep.

Cardinal Sean O'Brien, thick, swarthy, and not at all happy at the prospect of being awakened before his appointed hour, rolled in his bed and pulled the pillow more closely over his head. It did no good. The phone was loud, insistent, and came with none of the amenities of American phones – like an answering machine.

Groaning, O'Brien rolled over and slapped ineffectually at the nightstand, nearly overturning the glass of water he kept by his side at night. As he came fully awake, his fingers regained their dexterity, and he managed to snag the receiver from its cradle with an irritated grunt.

"Yes?" he said.

The sound of someone breathing was the only answer for a long moment, then, Bishop Michaels' voice crackled over the line.

"Sean?" he said. "It's Tony. I . . . I'm sorry to call. It's so late. I should just let you . . ."

O'Brien sat up and ran his hand back through what remained of his hair. He was alert now, and he detected something odd in his old friend's voice. Something he knew he should recognize, but that did not come to him immediately.

"It's fine, Tony," he said. "You never were one for ceremony, in any case. What is it?"

"I'm not sure," Bishop Michaels replied. There was a slight slur to his voice, and suddenly Sean knew what it was he'd heard. Tony was drinking. It had been a long time since he'd last helped his friend with that particular demon, but once the circuits connected in his mind, Sean knew.

"It's San Marcos, and Father Thomas. You remember I told you about the – disturbance last Easter Mass? Since then things have gotten a little crazy here, Sean. The media is up in arms . . ."

Sean thought quickly. There were a number of ways this could be headed, and he didn't like any of them, but if he chose wrong, he would be no help to his friend.

"So," he said softly, "I take it you still think there's nothing to it?" "How could there be, Sean?" Bishop Michaels asked. He sounded as if he were pleading, as if he needed someone to either back up his opinion or set him straight quickly.

"This is California," Michaels continued, "not the Holy Land, or even the Vatican. Oddballs and lunatics are regular citizens here – and the Church has had its fair share. I'm sure I'm on the speed dialer of every tabloid reporter and crackpot in the city."

Cardinal O'Brien leaned back against his headboard and focused. He knew that Tony wanted something, something he could provide, but he wasn't sure if it was help – or just a set of ears to listen, or a wall to bounce this off of. It was critical that he figure it out, because if the slur remained in the Bishop's voice, they'd have to send someone in – and Cardinal O'Brien did not want to see his old friend in that position.

"What can I do," he asked at last.

"I'm not sure," Michaels replied, his voice weary. "I'm not sure if I can do anything, either, but I intend to try."

"How," Sean asked.

"I wanted to give you a heads up, Sean," Michaels said wearily. "I intend to attend the Easter Mass at San Marcos this year. I'm going to film it – cameras directly on Father Thomas. The media will be excluded, of course. I've called in favors from the local police. They'll be lined up in the parking lots and on the road, probably even bring in helicopters, but they won't get into the church."

"Is that wise," Sean asked. "How will the parish react? Do they support him? Are they afraid? We wouldn't want to seem intrusive, or harsh."

"I'll keep it all as low key as I can," Bishop Michaels said. "I will do everything in my power to make it seem routine, as if maybe we want to have the film for training, or a documentary. I'll even pretend to believe, if it can help us through this and on to normalcy. Something. I won't come across as the ogre, but I have to set this to rest."

The line went silent for a moment, and Cardinal O'Brien broke that silence.

"What if you can't?"

"That's what you're there for, isn't it Sean?" There was a light chuckle at the other end of the line, and Sean relaxed slightly.

He stared off into the shadows of his dark bedroom. His mind was drifting, and he was thinking about other churches, other places, and other times. He shook his head, realizing the line had remained silent for too long.

"Try to keep an open mind, Tony," he said softly. "Call me, one way or the other, the minute the services have concluded."

"Of course," Bishop Michaels' chuckled again. "That's why I called you now, Sean. If this thing blows up in my face, I know you'll be there to wipe it off – but if it doesn't, I expect full credit for my good deeds."

They both laughed for a moment, then O'Brien's tone grew grave once again, and he asked.

"How have you been, Tony?" He hesitated, and then added, "You sound a little more tense than usual. Maybe you should pack up your things and pay a visit to Rome – unwind a little."

There was silence, just for a second, and then Michaels chuckled again.

"When this all blows over," he said, "I might just do that. It's been a very long time."

"That it has," O'Brien agreed in mild relief.

"Get some sleep, Sean. I'm sorry to have woken you so late. I spoke with Father Thomas, the priest I mentioned, earlier this afternoon, and it just wouldn't let me go, you know?"

"I do," O'Brien replied. "More than you know, Tony. Sleep, now, that has never been a problem for me. May God be with you, old friend."

"And also with you," Bishop Michaels replied.

There was an audible click, and then the dial tone blared to life. Cardinal O'Brien sat for a while, holding the receiver in his hand as the tone buzzed angrily through the silence. Then, as if waking from a light doze, he stared at it and placed it back onto the cradle, returning the room to silence.

He thought briefly of another man, a younger man. The Cardinal reached up without thought and pressed against his nightshirt with the palm of one hand. He felt the familiar bulge of soft leather, and he stroked it as he thought. Father Prescott was in South America, but he would be returning soon. If things progressed… Still, that was something to think about only if necessary.

He lay back, stared at the intricate pattern of shadows on his ceiling, and off to sleep.