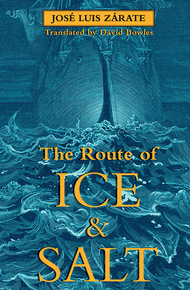

José Luis Zárateis a key figure of the Mexican fantastic literature of the 1980s. Together with Gerardo Porcayo, he created the first online Mexican science fiction magazine,La Langosta se ha Posado, in 1992. He is a winner of the Premio Internacional de Novela de Ciencia Ficción y Fantasía MECyF and Premio Kalpa. Zárate is best-known for a trilogy of short novels centred around key popular culture figures – Dracula, Superman and El Santo. He studied Linguistics and Literature and now teaches a course on fantastic literaturein his native city of Puebla.

David Bowlesis a Mexican-American author and translator from south Texas, where he teaches at the University of Texas Río Grande Valley. He has written several books, most notablyThey Call Me Güero: A Border Kid's Poems(Tomás Rivera Mexican American Children's Book Award, Claudia Lewis Award for Excellence in Poetry, Pura Belpré Honor Book, Walter Dean Myers Honor Book). In 2017, Bowles was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters.

Poppy Z. Briteis the pen name of author Billy Martin, who lives in New Orleans with his husband. His novels includeLost Souls,Exquisite Corpse, andLiquor. He is currently working on a nonfiction book about religion and spirituality in the work of Stephen King.

A reimagining of Dracula's voyage to England, filled with Gothic imagery and queer desire.

It's an ordinary assignment, nothing more. The cargo? Fifty boxes filled with Transylvanian soil. The route? From Varna to Whitby. The Demeter has made many trips like this. The captain has handled dozens of crews.

He dreams familiar dreams: to taste the salt on the skin of his men, to run his hands across their chests. He longs for the warmth of a lover he cannot have, fantasizes about flesh and frenzied embraces. All this he's done before, it's routine, a constant, like the tides.

Yet there's something different, something wrong. There are odd nightmares, unsettling omens and fear. For there is something in the air, something in the night, someone stalking the ship.

The cult vampire novella by Mexican author José Luis Zárate is available for the first time in English. Translated by David Bowles and with an accompanying essay by noted horror author Poppy Z. Brite, it reveals an unknown corner of Latin American literature.

An underground classic of Mexican fantasy, translated into English for the first time and championed by Silvia Moreo-Garcia, who published it. This is Dracula's voyage as you've never seen it before! – Lavie Tidhar

"A necessary and engaging addition not only to the always popular subset of Dracula-adjacent tales such as Dracul by Dacre Stoker and J. D. Barker, but also to the growing pantheon of retellings of horror classics from a marginalized perspective such as Victor LaValle's The Ballad of Black Tom."

– Library Journal"The combination of sensuality and slipping reality contains shades of Strieber's The Hunger and just a dash of Moby-Dick."

– Tor Nightfire"The language of this translation of The Route and Ice and Salt is consistently poetic and evocative, conveying the sense of desperate fantasy transmuted into psychological horror extremely well."

– Nerds of a Feather, Flock TogetherDemeter

One: Before the Storm

from 5 to 16 July 1897

At night: the smell, the weight, the feel of salt.

Much more present than the water on the other side of the wood.

Who could have fathomed?

Nights spent, not in dreaming of sirens of uncertain sex, but in the eternal, tireless caress of the grains that lurk within the liquid.

When the midday sun dries the sails, dampened by breeze or storm, they crust over with that omnipresent granular white that seeps in with the salty mist of the night sea, finding its way into our hair, between our fingers.

No place is safe. It burrows into every crevice of the ship, into the metal bunks, into our provisions, into the treasures that we attempt to keep from rust. Its presence is a mocking smile.

And when the men strip away their clothing, they find it between their thighs, hidden where groin and testicles meet.

The sailors are Lot's wife. Creatures of salt.

When I go to the forecastle, redolent with the absurd heat of bodies that rest in the midst of the swelter, I can almost see it accumulating on their indolent skin.

Who has tasted it? Who has savored ocean and flesh in that hidden place?

Not I.

I cannot.

I am the Captain.

Impossible that I order one of my men to come to my cabin and ask him to undress, much less insist he stand still and permit me to clean him with my tongue, lightly biting his flesh, trembling with craving for his skin.

And if there is no flavor?

That would mean that some other has saved him from the salt.

Then I should have to demand an accounting, impose discipline, require they reserve for me alone their salt, their warm sex.

But I cannot demand an accounting.

Not when the days are so long and we drift beneath the sun upon the windless water, measuring the hours by the slow drip of sweat.

In the distance, one can see the horizon move, a useless mirage: water in the midst of water, boiling.

At such moments, it is not difficult to imagine that we burn there.

How to deny them aught if these waters deny us all? Is it not better to know that an immemorial hunger was satisfied, that one offered himself—entirely of his own volition—to an appetite that creates us as it devours us?

Their bodies are their own.

Not mine or of some possible lover.

Theirs that sweat and the sweat of any man to whom they grant it.

The salt of life ….

It is in those moments that I yearn for the icy routes.

The Gulf of Botnia. The Baltic Sea. The North Sea.

Such strictures. The crew's rooms sealed. Men hidden in blankets and coats. Under siege, attempting to prevent the entry of the eternal, indifferent cold. We can slide over it or die upon it. It cares not.

Captains trapped in sudden ice, harkening to those deadly sounds—boats torn open by icy needles, metal giving way, crumpling under the weight of a million trans- parent blades—will not believe that the cold is not an enemy.

I have seen ice form on the horizon, huge landless isles drifting away from our route. The cycles of winter and snow have naught to do with the ships that cross their path.

The Northern Lights flare up and burn, though no man perceive them.

Ice is for other beings, its rhythms and reasons beyond our ken, its starkness for alien eyes.

The indifference of God, murmured by the world.

The cold suffices unto itself; the heat demands that we partake.

We can take refuge from the frost. It does not belong to us. We can cover ourselves with furs and approach the fire.

But what to do when the heat comes from within?

In the dead of night, our blood is like a sweat inside the body, warm sea nestled within our flesh, skin feverish and throbbing.

How to seek shelter from that which runs through our very veins?

Whoever dies frozen drifts away from his body, leaving in the midst of a merciful dream.

Whoever dies by fire remains trapped within that roiling flesh until the final moment, screaming until death comes like a balm.

Such notions occupy a man's thoughts beneath the motionless sun, when the shadows of the schooner are but warm shade. Steam rises from the waters. Sweltering air pursues us.

How delightful to walk naked in such heat.

But flesh fragments under the sun. First, cracks appear, then sores scoured by salt.

So, I must forbid it, order them to wear acidic clothes, astringent shirts, pants stiff with salt.

I ask them to seal themselves up with sultriness under those fabrics.

Not even below decks can I enjoy the sight of their bodies. If I stare too hard at them, they take my frank look as another order. They stand, saluting to their own chagrin before getting dressed to mine.

Their sweat (could it be otherwise?) makes me imagine firm muscles, taut veins.

Other captains ask why I choose men from certain lands, why sailors with exotic accents work with me.

I cannot answer with the truth, that it matters not to me whence they come, nor their race, nor the words that dwell in their tongues.

I look for smooth bodies, muscles along which sweat can freely run, liquid flowing, sliding.

Therefore, am I quite strict about their clothing.

For I know that beneath, there is almost no hair, naught to hinder wet caresses, fingers sketching desire.

Or eyes that also seem to touch the path of salt. And so, I abandoned the glacial route, the seas of ice, the dark blue.

An ill decision.

But this I knew from the beginning.

The sun dries men, overwhelming them with its weight. It makes them aware of themselves, aware that they swim in some sweltering miasma.

Their flesh barely contained. Always present, whispering its appetites.

But a prison nonetheless.

Therefore, in the few icy ports that our route touches, we leave but a meager guard on the Demeter, seeking stone houses where we can breathe the cold.

Our territory: boundary between flesh and world. Cold without, we men within our skin.

And even there, despite our memories of the broiling sun, we long for fire.

We seek, then, the heat of other flesh. The salt on other skin.

My crew invites me to partake of wine and beer at their side. Sometimes, they sacrifice part of their wages to buy me such women as they find comely.

I choose the youngest ones, small-bosomed, resembling more children than females. The whiter the better.

But such specimens are dear and I dare not buy them for myself.

For hours, I close my eyes and imagine that other lips produce those caresses. I ask them not to speak, to stop being themselves, so that my fantasy may more readily transmute their flesh and I can achieve a weak, trembling orgasm that seems to escape from me, spilling out like sand.

The harlots prowling for crews are not unaware that— during the still hours upon the water, when all that exists is the certain solitude of darkest night and the slow breathing of the other sailors—one will seek, sooner or later, the taste of salt between the thighs.

And so, those women also sell their sons.

Devastated boys, like their mothers, beautiful only to newly landed men, their vision scorched by the sun, clouded by drink.

Sailors purchase such ephebes. Why should they not?

It is no secret.

On the islands, the boys are sold more cheaply. It is not uncommon to find them in the ports along our route.

Is Greece not renowned for the practice?

But I do not buy them. I remain with my men, pre- tending to regard women, sharing anecdotes that matter little to anyone.

I cannot buy them.

Not when I accompany my crew.

I am the Captain. I hold in my hands the lives of my men.

My men.

Along the route of salt, murder and intrigue are simpler. Muscles burn and seek to give that burning some meaning. To move, to smash against something; to act.

Against what? Against what, in the midst of such still- ness?

There can be no favoritism upon my schooner.

That is why I shall not choose any man. I shall never keep watch with those whom I desire. I refuse to let them walk naked.

I dare not.

Thence the difficulty of gathering my crews: hairless men from icy countries.

I prefer that the heat make them drowsy, that it be a heavy blanket over their heads. I do not want men accustomed to heat, whose brown skin can bear the full brunt of the noonday sun.

I do not wish them to laugh at my command to clothe themselves.

I should be wholly unable to get away from such men. I should never stop looking for the hidden taste within their bodies.

The salt of their seed.

Crews come and go. On each journey a new man, another who leaves.

They do well. I am not a good captain. Many things distract me.

They are uncomfortable with me. On a schooner, there is not room enough to dissemble their exasperation.

In Varna, I thought I should lose all my crew. After serving for a long time among the Southern Sporades in the Aegean Sea, supplying the Dodecanese Islands, they must be weary of the heat, of me, of the old Demeter, docked so many useless days in the port of Rhodes.

The Black Sea must have reminded them that they were men of cold climes; connoisseurs more of ports like Odessa, Sevastopol, Sochi, Batumi than of islands with strange names: Schinoussa, Nisyros, Laconia, Kalymnos. I know (how not to know?) that they ache for white- skinned women who speak their tongues, that they are plagued by memories of frigid lands, of ice creaking in storm winds.

What could the women of the Greek islands know of the howling Baba Yaga, her ramshackle home creeping through snowy forests on looming rooster legs? Naught. Swarthy women will smile at such an image, unable to protect sailors from the fear that their mothers' whispers instilled in them during endless winter hours.

They should have left to seek those white bodies, those shared memories of ice. But they have remained, nigh-on to a man, at my side.

We have arrived in Bulgaria. They have gone ashore without asking for extra coin to sustain them while they find another ship.

They spend their hours in dark taverns, while the owners of the Demeter prepare contracts, organize another trip, trace another route for us.

When it is time to sail, the men will return to the schooner as if it were their home, the only familiar thing in the heart of such foreign lands.

They have not remained for me, for love of this old ship.

It is simply difficult to find other jobs. All are as bad as the previous one.

I should have preferred that they leave.

With every sailor who travels with me for the first time, there is a chance.

New blood is always necessary.