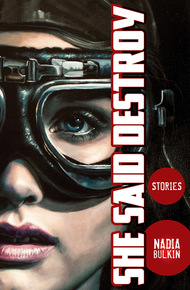

NADIA BULKIN writes stories, thirteen of which appear in her debut collection,She Said Destroy(Word Horde, 2017). Her short stories have been included in editions ofThe Year's Best Weird Fiction,The Year's Best Horror, andThe Year's Best Dark Fantasy & Horror. She has been nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award five times. She grew up in Jakarta, Indonesia with her Javanese father and American mother, before relocating to Lincoln, Nebraska. She has a B.A. in Political Science, an M.A. in International Affairs, and lives in Washington, D.C.

A dictator craves love–and horrifying sacrifice–from his subjects; a mother raised in a decaying warren fights to reclaim her stolen daughter; a ghost haunts a luxury hotel in a bloodstained land; a new babysitter uncovers a family curse; a final girl confronts a broken-winged monster…

Word Horde presents the debut collection from critically-acclaimed Weird Fiction author Nadia Bulkin. Dreamlike, poignant, and unabashedly socio-political, She Said Destroy includes three stories nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, four included in Year's Best anthologies, and one original tale.

Nadia is one of two writers in this bundle whose work I bought when I had the chance! Ross Lockhart says, "Nadia Bulkin's been astounding me since I first read "Red Goat, Black Goat." She brings a rare—but welcome—politicality to horror fiction that elevates it far beyond simple scares and funhouse grotesqueries."

"Bulkin delivers a dose of delicious darkness with her debut collection."

– Silvia Moreno-Garcia, New York Times bestselling author of Mexican Gothic"Great horror happens when a story reveals some profoundly personal truth or when it reflects something ugly we can recognize on a broad, systemic scale. Nadia Bulkin writes what she describes as "socio-political horror" and it colors many of the stories in a debut collection that will surely be recognized as one of the year's sharpest."

– Tor"Within these pages, you'll find cold hard death, wry dark humor, pain and suffering, hauntings, strange religions, twists on cosmic horrors, familial legacies, and much more. Do yourself a treat, get this book, mark out a nice block of uninterrupted time, and sink on in. Just remember, this is the heavy stuff, the dark stuff; this is not gonzo splatter or quiet literary but its own deep brand of dread-at-the-core."

– The Horror Fiction ReviewIntertropical Convergence Zone

At the beginning, at the very very beginning of time, the General ate a bullet. Those of us who weren't sure about the dukun were worried, and we sat with our elbows on our knees and our chins on our fists around the table, under the single naked bulb with the dangling string. The dukun, who said his name was Kurang, had already washed the bullet in holy water that he said came from the very north-of-the-equator springs the Sultans of Sriwijaya bathed in. He said some incantations and then told the General to eat it.

"There. Eat. Eat it. It will make you know things about people, so you know where to aim when you shoot them."

The General stared at the bullet until sweat dropped onto the plate.

Kurang bent over. "Mister General," he said, "I promise, good things will happen. You'll see like a garuda, Mister General." He always mocked us. Kurang was one of those villagers who doesn't really give a shit about national unity. They're godless men and that's another thing that bothered me, because the General was devout as all hell. "And then you lift your gun, or they lift their guns…" He looked at us, the uncomfortable posse. "And you know exactly where to aim. This bullet has the gift, Mister General. It will give you the gift too."

We'd pulled it out of a dead man two days earlier. A clean heart wound that had punctured a major artery—he died immediately. It was perfect, we thought as we smoked our Marlboros and sat on our folding chairs, watching the corpse. Of course we bound him up first and put him against the chalk sketch lines on the basement wall so he wouldn't squirm and so we knew where to nuzzle the barrel. What Kurang told us was this: the dead man has to be the right man, the bullet has to go through the heart, and the bullet has to kill right away.

He was someone who'd been in on our list for a while. A Communist, of course, a party pusher who carried around paperback Mao and mingled with pushcart-peddlers and pretended to be one of them. He was going to go eventually, so we figured, may as well be now.

"Eat it, Mister General. Don't you want to be a great man?"

He took it like a pill. He started choking. We pushed our chairs back and got up and cursed at Kurang but Kurang was already right at the General's side, helping him swallow the tea. "There, there," said Kurang. "Hush hush, it's okay, Mister General."

We waited for something to change. Nothing did at first. The General made a joke, we laughed; he announced he was going to bed to sleep, and Kurang said that was a good idea. The General walked out of the room rubbing his ribcage, looking puzzled. We said to ourselves: okay, if he's dead tomorrow morning, so is that dukun.

But he wasn't dead. He was up bright and early and he wasn't wearing his glasses when we had our morning meeting in his office. He doled us out assignments. They had schedules on them and everything. We asked him why he wasn't wearing his glasses and he said, "Don't need them. I feel so sharp today. It's like looking through a submarine periscope, you know?" And he made this pantomime motion of a navy admiral looking through a periscope and adjusting the lens and then laughed. We all laughed. He laughed until he coughed out a tiny pellet of a bullet that burned one of his memos. We asked the dukun but he said that was a normal side effect.

So that was how it started. Nothing very strange. My daughter was drawing people's faces back then, which was also not very strange, except she never filled them in. Whole families without faces.

***

A week later the General had indirectly sent ten of the most dangerous Communist strategists into the next world. I assume they went to hell, but I've never been to check. They were hidden ones with inconspicuous day jobs—moonlighters. One was a doctor, one taught mathematics. The Communists were squabbling now like hens without a rooster, and they went looking for new warmth. They went for navymen. I don't know what's wrong with the navy, if it's from fighting pirates in the Sunda Strait or if it's just being seaborne that fucks with your head, but they had too many dinners with Communists. I have always thought this.

I was getting out of the lounge when I saw Kurang on the street corner in this horrible fake trenchcoat with buttons hanging like eyes out of sockets. He wasn't even smoking, he was just there.

"What? Looking for a hooker?"

"You want to help Mister General, right, Lieutenant?"

I looked around for any President's men. Just zombies and shapeshifters, hanging around in rags and eating noodles, probably infected with hookworm eggs. I looked at Kurang. "Are you following me?"

"You're the best Lieutenant. Mister General needs to get those sea-men to see his way, see?"

There were all these prickly red, bulging spots on his face. Sometimes I thought they were moving, but then I'd think, no, trick of the light.

"There's this knife, a kris. It's on one of the outer islands. Right now a fisherman's son has it. If the General eats it he will be able to draw people to him and command them, you know, make them see like he sees. You go get it and bring it here, we'll dress it up nice."

It was for the General, so, okay. I love this country, and Communism's a Satan and the President's its lackey. Leave it to them and we'll all be starving and dying in shrapnel and colorful bombs. No, no. We need a man like the General, an honest man. He's one of us.

Before I left I went home. My daughter had begun to draw deep-sea creatures by then. She gave them all to me, slips of paper that she folded into infinite squares and I put in my wallet. "To protect Daddy," she said, and then went back in the house. I hated the pictures. Curling, coiling beasts. I didn't want their protection, but I kept them anyway.

***

I stood on the sand, shifting. The waves there came from Australia. The dukun told me the name of the island and village and the man, and I asked the locals to fill in the rest. When they saw my credentials and I said that the General needed their help, they helped me. Sometimes I had to show them my gun.

I got to the beach by motorbike. That was our last frontier, those eastern islands. They were populated by people but I think those people were a different species. It was in their eyes. I could tell. Even the children had that look. They all had filariasis, and maybe that was why—microscopic worms sleeping in their veins. It's a horrible disease. They're the only people in this heat-soaked country who shiver in the sun.

At the beach there was no one. There was a limping half-wild dog, and there was a kite. I thought the men at the convenience store had lied to me, it wouldn't be too surprising, but then I saw him—seventeen years old, curly black hair, standing by his father's boat. He had the kris sticking out of his backpocket. He didn't know what to do with either. I went toward him and stood on the shifting sand and called to him to give me the knife, I worked for the General and I needed it.

His lips moved and his head shook to say no, but I didn't hear any words. All I heard was the sound of a low motor, not the Pacific, but a real low motor that opened up with a chainsaw sound into a voice—like jaws being torn open and held there. It was the knife. I saw its handle swivel in the backpocket of his trousers—it turned to look at me.

It said, "Eat me, Lieutenant."

I didn't dare look at it even though its booming voice pounded in my ears. I held out my hand to the fisherman's son, and said something to him—I don't remember what because I never heard it. All I heard was:

"Eat me and be great. I will live between your lungs and I will give your voice a resonance you have never known. Eat me, Lieutenant."

The boy backed onto the damp, dark parts of the sand. The knife was thunderous and the waves were rocking. He shook his head no no no, and then he reached behind his back and grabbed the screaming knife and yelled.

When I shot him he was flying toward me with the kris quivering in the sun. I saw all the way into the back of his mouth. His body went sloshing to Australia on a bed of foam but the knife stayed, stuck in the sand. Hermit crabs came out of the spot in droves where it burrowed. All up and down the beach it called and called. And I was all alone to listen to the beached monster. I thought this was the end of the world. All I saw was ocean, the color of sky, and all I heard was the dark sound of power being born. I wrapped my hand in cloth and I pulled it out of the sand. There was my face in the blade. By then the knife was no longer articulate. It was just the sound of the great furnace, the great God, roaring in want.