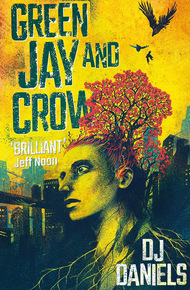

DJ Daniels is an Australian author and musician. She writes when she manages to get her husband and two daughters out of the house and during lulls in the ongoing dog-lizard war. (Lizards are well ahead.) Her first novel, What the Dead Said, was followed by a raft of short stories which have appeared in publications such as Aurealis, Andromeda Spaceways Magazine, and So It Goes. She was a judge for the 2012 Aurealis Awards and is one of the Sydney Story Factory's Ambassadors of Ink.

"I WAS MEANT TO COME TO BARLEWIN, BUT I WAS NEVER MEANT TO STAY."

The half-forgotten streets of Barlewin, in the shadow of the High Track, are a good place to hide: among the aliens and the couriers, the robots and the doubles, where everyone has secrets.

Like Eva, a 3D-printed copy of another woman, built to be disposable. She should have disintegrated days ago… and she hasn't.

And now her creator wants her back.

"That old, old question – what does it mean to be human? – is given a new configuration by DJ Daniels: what does it mean to be human or otherwise? And it's the otherwise that really counts, in a brilliant story that celebrates existence and survival on the newfound edges of life, and love. The fight back against disposability starts here!"

– Jeff Noon, Arthur C. Clarke Award-winning author of Vurt and the Nyquist series"a bizarre yet enjoyable read from a new voice in science fiction which offers an interesting look at humanity, identity, hope and friendship in a peculiar new world"

– Red Rocket Panda"It's an idea-driven science fiction novel…new ideas that here burst forth almost at once, and then continually."

– Strange Horizons"It's a fresh, strange and thought-provoking literary exploration of humanity and identity in a trans-human world. It's a celebration of creativity, imagination and originality."

– RisingShadow.netI THINK OF it as a ripple, a ripple of favour and exchange. Of course, the effects spread wider than I can see—there is intersection and interference—but this is how it goes as far as I know it, how the ripples flow in the little world of Barlewin. Sometimes I imagine I'm a bird, that I can follow them along, but there's no need for that, not really, because I watch closely and I'm beginning to know this place well.

First of all, there's a package that enters Barlewin, up by the water tower usually. I'm still not sure why the couriers feel safe there, maybe it's the protection of something so large. The feeling you can hide. Perhaps because you're hidden from the gaze of the man painted on the water tower, the one with the huge head and the large eyes and the crazy hair and the comb. It's hard to tell if he's friendly or not.

I can tell who has a package because there's a certain kind of walk that lets me know something's going on. It's not a determined walk. I see plenty of that. Along with the shy, timid, don't-take-any-notice-of-me kind of stuff. This walk is sure, but relaxed. Deliberately relaxed. It says, I'm in control and there's nothing going on. Except there is.

More often than not the package changes hands close to the water tower. But the walk doesn't change, it's passed on to the next person in the relay. There's no favour, not yet, just a delivery. Drugs, it's probably drugs. And if it is, the parcel will most likely find its way to Guerra. Once it's there with him, it's all potential. All expectation. The package will be broken up, and later, at night, Guerra's people will take the smaller parcels back out into the world. Then there will be smaller, moonlit ripples.

Sometimes the package is something for the robots. I love the robots. They call themselves the Chemical Conjurers. Their package might contain chemicals for their routine, or it might contain other stuff people know better than to ask about. Though people usually don't think the robots would do any harm. And for those who know, the robots can be bribed to provide a distraction (a smoke, a smell, a spectacle) at the appointed time and place. They did it for me once, and I still owe them. But they don't often have deliveries from human couriers. They like to get their packages by delivery drone. It amuses them, I think. I've seen them set up mazes, see if the drones can find them, but they mean them no harm. Once, when one of Guerra's people tried to catch a drone, they sprayed him with something cloudy and dense so it could fly up and away.

Sometimes the courier walks in the other direction, goes north of the water tower. The farms are there, scratched-out places to grow tomatoes and spinach and beans and whatever else. Maybe the package is worms, or fertiliser. Most likely it's not. Most likely it makes its way to the shipping container at the side of the farm and hides between the spades and the secateurs and the rope. I don't like to think about the farms.

I can always tell if it's something for the Tenties by the look on the courier's face. She'll be walking fast, not even bothering to look relaxed. The package will be soft and squishy and the courier wants it out of her hands, she wants it gone, whatever it is the Tenties have asked for this time. Those deliveries make me laugh. The Tenties are crazy. I love the way they change. Every week there's something new and they never get it right. They know enough to realise I'm not real, but not enough to ignore me like the others would.

And sometimes the package makes its way past the big screen and the market shops and into the tenements. Up alleys and through doorways where there are special knocks to get in, or certain words to say to a man sitting to the side. Then there are stairs, there are always stairs, and a search for the right number. If a courier was looking for me, they'd need to climb up and up: I'm as high as Guerra. And in this room there's lots of glass to see out, down to the streets. That's how I know about the packages.

But there's never been one for me