As a mystery reader, Lauryn Christopher likes figuring out "whodunit" as much as anyone – but as a mystery writer with a background in psychology, she's much more likely to write from the culprit's point of view, exploring the hidden secrets driving their choices. You can see this in her Hit Lady for Hire series, as well as in her short crime fiction and cozy capers, which have appeared in a variety of short fiction anthologies.

Read Lauryn's musings on storytelling, find links to more of her work, and sign up for her occasional newsletter at her website: www.laurynchristopher.com

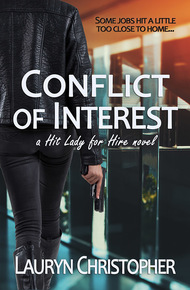

When an assassin has work-related issues, someone usually ends up dead

It's a bad idea to piss off a professional assassin, and Meg Harrison - corporate spy and sometimes assassin - is definitely pissed off. Not only has a new, and very irritating, client hired her to kill her own sister, but to top it all off, Meg didn't even know she had a sister. For Meg, this is a contract that hits a little too close to home.

Then, for good measure, I asked another multi-genre and prolific writer, Lauryn Christopher. Lauryn is not only a writer under many names, but under another name yet is also a well-known editor. I wanted her novel Conflict of Interest, a Hit Lady for Hire book, mostly because it makes a fun companion to my Mary Jo Assassin novel in this bundle. – Dean Wesley Smith

"...Christopher turns the hit-man formula on its head, and in doing so gives us a surprising and entertaining read."

– Big Al, Big Al's Books & Pals"...a well-organized, thrilling read."

– Jadis Shaw, www.junipergrove.net"...a five star must read."

– ake Hardman, jake-hardman-thrillers.blogspot.com"...well-written, intricately plotted, and full of surprises."

– Donna White Glaser, www.agratefulbookaholic.blogspot.comChapter 1

"Listen very carefully, Harry: discrediting Whitfield's lab, destroying his work, and smearing his character are all covered by the original fee I quoted you.

"Murder costs extra."

The voice on the other end of the line sputtered in reply.

I looked heavenward for a hint of respite, but was rewarded with nothing more than a view of recessed ceiling lights, decorative crown molding, and automated sprinkler nozzles.

So I sat, perched on the corner of my desk, and alternated between gazing out the window at the Philadelphia skyline and studying my nails as I listened to Harry's ranting.

You never really know what you're getting into when you take on a new client.

There are times when I just don't know if they're worth the effort.

Take this guy. God only knows how Harry Saunders found his way to the heavily encrypted website where prospective clients can post their dirty laundry for freelancers like me to pick up if it interests us – it's not exactly like you can Google it, and we certainly don't hand out "Hire a Hit Man" business cards with the URL printed on them – but here he was, on the phone with me for the third time in as many days, trying to negotiate the cost for my services.

I don't negotiate.

"Let me put it this way, Harry," I said, finally managing to get a word in edgewise. "You're obviously new at this, so I'll give you a tip: when you post a job, post the whole job, not just a teaser. It'll save you a lot of dead-end conversations like this one. OK?"

I walked over to the window as I talked. The downtown view from my office windows provided inspiration as well as perspective on dealing with difficult situations. I continued, taking control of the conversation.

"Make the payment like I told you. In full, in advance, for the services you want. No partial payments, no cancellation options, or any of that other bullshit you've been trying to foist off on me. When you've made payment, I'll do the job.

"Or don't, and you can re-post your listing and I'll forget I ever heard of you. Your choice.

"Either way, we're through negotiating. Understood?"

I clicked off the call before he had a chance to start complaining. Then I tapped through the phone's menu to delete the call log and reset the phone's settings back to the factory originals.

I turned the cheap prepaid phone in my hand for a few seconds – it was my third new phone this week – then with a sigh popped out the battery and memory card. I snipped the memory card in bits and wrapped them in a tissue for flushing down the toilet later, then put the handset and battery in postage-paid mailers to send to separate refurbishing companies.

It was standard procedure. Get the incriminating phone number back into the system for someone else to use as quickly as possible after a call.

Eliminate any chance of it being traced back to me.

I got another prepaid phone from the lock-box in the bottom drawer of my desk and activated it, using a name chosen from the novel I was currently reading and a randomly selected area code – Wyoming's, this time – carefully tapping the tiny keys with the tips of my fingernails.

The fake nails were a pain in the ass. I'd already broken one and snagged two pair of nylons on the ragged edge.

I reached across my desk and pressed the intercom button, my index finger proudly displaying the offending nail.

"Jessica," I said.

"Yes, Meg?" came the tinny reply.

"Get me a nail appointment, would you?"

"Hating the nails?" I could hear the smile in her voice. "Sure thing. Where?"

"Anywhere I can get in today. Otherwise I'm just gonna rip these things off." I said, and closed the connection.

I sat there chewing on the torn nail. Harry was still pissing me off. Of course, Jessica knew nothing about Harry. Or most of my confidential clientele, for that matter.

Better for her that way.

To her, I was Margaret Harrison – Meg – corporate consultant, and her boss. She scheduled my appointments, answered my phone, and ran the occasional harmless errand.

But to people like Harry, I was the nameless person who responded to their anonymously posted requests for information about their rivals; the one they turned to when they had unsavory tasks to do but didn't want to get their hands dirty.

When a name was required, I was Megan Harris.

# # #

I always check out new clients. Both the legitimate ones as well as the more, shall we say, questionable variety. Especially when they're stupid enough to give me their real names. I want to make sure they're not stupid enough to make mistakes that will compromise me in any way.

Harry Saunders had been easy enough to find on the Web.

I reviewed my notes.

Harry was well up the food-chain in the biofuel industry. Owner, president, and CEO of Saunders Biofuel out of Des Moines, Harry was a prominent local citizen, donated generously to charities, and was something of a "man about town."

He was active on social networking sites, and posted numerous pictures of himself entertaining assorted celebrities and beautiful women.

Mostly beautiful women.

His rival, a Dr. T.J. Whitfield, was doing research toward enhancing the capabilities of fuel cells. Whitfield had published only one paper, presenting it at a venture capital conference a few months back; otherwise, he was a blank as far as the Web was concerned. No social networking contacts. No blogs or personal websites. Founder of a private research lab, established the previous year, but even the lab had an insignificant Web presence.

If I hadn't been planning to kill Whitfield, I'd have added him to my list of potential clients, and contacted him directly about the possibilities of enhancing his corporate image to make the Lab more appealing to investors.

I tapped into one of my more useful side businesses – a background checking service – but with nothing more than the partial name to go on still came up with nothing conclusive on Whitfield. It was very strange. I should have at least been able to find records of his college degrees.

It was possible that Whitfield was one of those reclusive types, who eschewed credit for cash-only purchases, and had no particular vices to bring him to the attention of any public records.

From Harry's perspective, though, Whitfield was a solid rival, too close for comfort to a breakthrough that would threaten the market for biofuels.

Or, I suspected, a breakthrough that might result in a decline of increasingly difficult-to-justify Federal funding for Saunders Biofuel.

I encrypted the file and closed my laptop.

There's good money to be had in corporate rivalry.

On the legitimate side, consulting for Fortune 500 firms paid for a nice office suite in downtown Philadelphia, an assistant to book my appointments, to-the-limit 401-K and IRA accounts that hadn't been too badly damaged by the fluctuations in the economy, and a restored Victorian-style home in Philadelphia's Germantown suburb.

Off-the-record information brokerage – which was really nothing more than ultra-private consulting for a very exclusive and high-paying clientele – had funded a second portfolio which I had managed to salvage through the recent recession through a combination of ultra-conservative investing and insider trading. In addition, I owned a half-dozen small manufacturing companies, both in the U.S. and in developing nations, that had survived the crisis.

Income from multiple mortgage-free vacation homes in trendy resort locations were the icing on the cake. They had long-since earned back the investment in rental fees, and even in bad times brought in more than enough to cover property taxes and maintenance expenses.

These days, no matter how financially secure you think you are, it's just good business sense to have a backup plan – I advise my clients of that very fact regularly, and am not above following my own advice.

Or charging for it.

As I see it, if the client's willing to pay, I might just as well take their money as someone else.

But I got the impression from my earlier conversation with Harry that he wasn't entirely sure he wanted Whitfield dead.

So I set the price high.

Higher than I expected Harry to be willing to pay for a service he was uncertain about.

# # #

"Are you sure that's what you want to spend your money on, honey? Is that what you really want?"

It was my father's voice I was hearing in the back of my head.

A voice I hadn't heard since I was nine years old.

He was always doing that to me – sitting there in the big brown easy chair, asking me if I was sure I wanted to spend my allowance on the new book or doll or whatever had caught my fancy at the time.

I'd be all excited about my planned purchase, scraping together every bit of my saved-up allowance, and run to him, breathless in my enthusiasm.

And then he would plant the seeds of doubt.

"I don't know..." he would say, folding up his newspaper and explaining in patient detail why the object in question should be questioned further.

If I somehow managed to remain undaunted in my desire, he would change tactics, questioning my childish wisdom in squandering my finances in such a foolhardy fashion.

The seeds of doubt would sprout, mature, and bear fruit quickly under his masterful manipulation, until I was certain that I, a mere child, couldn't possibly know what I wanted as well as he did.

I would give him my precious handful of coins, and go away, never quite sure why I thought I had wanted the original item in the first place. My father would pocket the money, and return to his newspaper.

Sometime later, usually upon his return from his next sea voyage, he would present me with his version of what I wanted.

Instead of the picture book I had asked for, I remember him giving me a tattered, second-hand novel, totally unsuitable for a small child, but which I struggled to read anyway.

Instead of a doll, he gave me a sewing kit, and the opportunity to refine my homemaking skills by mending a basketful of his work shirts.

Whatever else was in the small, brown paper bag he always came home with wasn't for me.

When I was nine, he went on a trip and didn't come home. A few weeks later Mom got a letter. She read it, threw it into the fire, then just sat and cried for a couple of days. After a few more days, she packed up his things and sent them away. All she ever said was that our father wasn't coming back.

There was never any explanation.

My siblings and I tiptoed around the house, not knowing what to think or say.

I wished he would come back. Even if he only brought me another tattered novel.

Fiduciary responsibility, learned the hard way.

And now I was teaching it to Harry.