Jason Henderson is a Locus bestselling author of novels, comics and games. He's the author the hit Alex Van Helsing series, the creator of the comic Sword of Dracula and writer for the comic Ben 10 from IDW. He also hosts the weekly horror movie podcast, Castle of Horror. An attorney, Jason lives in Colorado with his wife and two daughters.

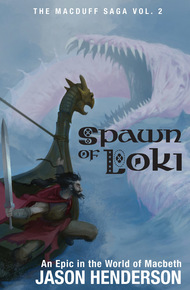

Lay on, Macduff! Off the coast of France, an insane monk accidentally raises Loki, the God of Mischief. Loki has a plan to unleash the end of the world. Now only Macduff, the Iron Thane, can raise an alliance of gods and men to stop Ragnarök in its tracks.

Lay on, Macduff! Jason Henderson came up to me at Denver Comic Con with several books published and a great personality. He told me about these fantasy sequels to Macbeth, the continuing adventures of Macduff. We've been working with him to release this book and its companion, THE IRON THANE. – Kevin J. Anderson

CHAPTER ONE

Macduff turned on the coast of Normandy in a tiny boat, as if he came from nowhere. There was a former Celtic funeral mount off that coast, two hundred and fifty feet of rock rising out of the sea, nearly half a mile in diameter. Twice a day the tide came in and cut it off from the land entirely, "in peril of the sea." And on that rock stood a monastery called Le Mont Saint-Michel, which played host to William, the Duke of Normandy himself. Macduff fit in there just fine.

O O O

As the first lights of dawn came into the cloisters, two swords clashed and sang out.

"Have at you," said William, looking out from under his black bangs. His thick, bull-like neck was set as he held the sword in front of him. His opponent, dressed in several layers of clothing and a red cloak that was becoming speckled with the slight snow that blew over the morning, swung at him, and William parried the blow. His sword came around and down with that of his opponent, and William brought his up and across. The man in the red cloak easily parried William's blow and laughed.

"Surely you can do better than that," the man said. The man in red was older by many years and gray of hair—indeed, he seemed downright gray in general. A black patch hung tightly over the swordsman's left eye.

William stopped for a second and lowered his sword. "Macduff," he said, "your French is improving."

"I'd rather not discuss it," said Macduff. Seeing William with his guard down, he swung hard across. William barely took a moment to register this and moved out of the way, blocking the blow with his own sword as he moved back.

"That wasn't fair, Macduff."

"Life is rarely fair," said the Thane of Fife.

William was a very busy man. In that cold February of 1058, William was well under way with his program of consolidating his power in Normandy and beyond. It was a heady time. The Duke's entire court had been moved here to this natural coastal fortress. Few doubted that there would soon be war. Just as every day the artisans crafted and sculpted what would come to be one of the greatest cathedrals in Europe, so grew the base of power held by William. The Duke had a lot on his mind.

But for the past month, in the early morning hours before his duty as ruler took full hold of him, he had found some solace and focus in his meetings with the strange man who had come one cold morning, quite out of the blue. Out of the gray, rather. The court was still telling stories about how the fog had lifted to reveal a small boat with one man in it, a man who said he came from the court of King Malcolm III of Scotland.

This strange Scot—Julian Macduff Scotus, the "Thane of Fife," as he called himself—had quickly found himself a place at the monastery, had taken up a cell, and performed regular duties there. As a noble, William had offered him a place of welcome in the court, but Macduff had preferred the other way. And so it was that they met in the mornings and tried to kill one another.

The duel was in full swing, now, as Macduff and the Duke pushed one another from one side of the cloister to the other, and the conversation wandered.

"… Scots sports are all alike, from what I can tell, then," said William.

"Nonsense," said the Iron Thane, swinging at the Duke's legs. The blow was blocked, of course.

"All right. The one where you throw the great log …"

Macduff nodded. "Caber toss. A very difficult sport."

"You throw a thirty-foot pole?"

"Forward. And it has to flip over and land pointing away from you."

"Hmm. And the weight toss?"

"You take a fifty- or sixty-pound weight," Macduff paused to knock William's sword away from his head, "and you throw it over your shoulder."

"Ah. And the sack?"

"You take a great, heavy sack of grain and you—"

"Throw it." William jumped over a low blow. "I'm beginning to see a pattern here."

"Well, there is the tug of war …"

"Where does all of this throwing get you?"

"It develops stamina. Good for the soul. And some of our greatest achievements were accomplished by throwing things."

"As in?"

"Have you seen Stonehenge?"

"Mon Dieu …"

"An afternoon."

"Ha!" William cried. Macduff had to concede that William's sword was indeed leveled at his neck. The Iron Thane dropped his sword. "Finally!" exclaimed the Duke. "You know, I don't recall ever beating you before." William let his own sword drop and leaned back on a wall, panting.

"You see what learning French has done to me," said the Thane of Fife, smiling. He joined William on the wall. His breath was steady yet.

William looked at his sparring partner. "How fares the religious half of the rock?"

"I cannot complain," said Macduff. His one eye was leveled out over the wall and into the foggy dawn. "At least I already know Latin. How fares your global conquest?"

William looked at the wall. He was half joking when he said, "Do you think they suspect?"

Macduff raised an eyebrow in response. "Just be careful, and keep your head about you."

"We're safe here," said William.

"Most likely."

"I have a capital, you know," William said. "I'm building one. In Caen. With another monastery, I think."

Macduff was watching the snow twist in streams and fall on his cloak. "You have supported the Church a great deal."

"Deus juvat, yes?" William indicated the iron badge that held Macduff's scarlet cloak together. It was Macduff's identifying mark, the badge of the Macduffs. A lion sat on its haunches and held a broadsword aloft in regal defiance. Underneath the lion's paws were the words Deus Juvat: God helps. William smiled and tapped the badge with his finger. "We need all the help we can get."

"Just be careful," Macduff said, and his one eye crinkled.

"What?"

"Just be careful," the Iron Thane repeated. "Ambition isn't everything."

"But it is important. Glory should be sought."

"Truth should be sought." William looked into Macduff's eye and saw that the man was serious. Macduff continued. "You're a good man, William. Don't waste yourself."

William slid off his gloves and slapped one of them against the other in his palms. "Will you join us for supper in the refectory tonight?"

Macduff thought. "I have some reading to do."

"There will be a reading there, of course, the monks provide that. And my favorite jongleur, Taillefer, shall be reciting Roland again."

Macduff ran his fingers through the snow in his hair. "I must decline. I am deep into Cynewulf's verses; the library here is remarkable."

"I shall tell Abbot Ralph that you said so," said William. He was proud of his extensive contributions to the church and he liked it when the results were acknowledged.

Macduff got up and began to walk toward the passage into the nave of the church. After walking a few feet, he stopped and turned back to see William, still sitting. "William, what is it that you want, to be king of England? Why England?"

William looked at him, as if the question were ridiculous. "It's the size of it." He took a breath. "Just across the water. A new world, Macduff, from the ashes of the one we live in."

Macduff stood still for a moment, watching the snow in the cloister next to his royal friend. He was remembering an entirely different king, and a very similar ambition. Ah, what fools these mortals be! another friend had said. The red of his cloak reminded him of too many fields. "King Harold of England just saved your Norman lives a few months ago. I … hope, for your sake, that you get what you need. But I hope it doesn't kill you." He thought for a second. "Or worse."

"Worse?"

"There are worse fates, my young friend," said Macduff, over his shoulder. The snow punctuated his words as it crunched under his boots. "Much worse."

O O O

The monastery at Mont Saint-Michel spiraled upward in a series of buildings stacked precariously atop one another around the side of the rocky precipice. It was a warlike abbey: stark, vigilant, brooding. And in the center of it all, any thinking man would insist, was nothing but ton upon solid ton of rock. This, of course, was wrong.

Down, down into the carved tunnel stole a figure dressed in a monk's habit. The tunnel itself, the mildew and the stains, was old, built and hidden long before the construction of the Church's stronghold in the early eighth century, before even the Celts of old danced there. Few had seen it or knew what secrets lay in the bowels of the Mount, and only a few immortals, perhaps, knew what forces had been at work to keep it safe amid all the foreign building that went on. Those who knew never told.

O O O

From moment to moment, Lucius of Avranches would flicker in and out of awareness of what his body was doing, but it was as one sees one's movements in a dream. He heard the sound of dripping water seeping from ancient cracks in the rock, and he heard his feet smack against stone stairs. He saw the torchlight flicker and illuminate his own hand as it swayed to and fro in the dark, leading him ever further down. He was being led and, though he could not have controlled his movements had he tried, he made no attempt to break the spell. He felt refreshed.

But he could see, all right, he could make out the Runes carved into the steps that he traveled, and he could read them as had been his skill and life's study, as had finally, somehow, caused him to find this old place.

Years he had studied, when all of his fellows laughed at his diligence, as he studied the Runes in their infernal, ancient shapes and deciphered the texts, checking the known translations again and again. He had seen their sneers as he had likened the old Odin, who hung on a tree to gain wisdom and traded an eye for it in the end, to the first man, Adam, and the second Adam, Christ. Odin had discovered the Runes. And the Runes, tree-like and spindly, and carved onto the rocks passing under his smacking, other-controlled feet, told all.

Lucius' mind floated as he rode his body along. Did he believe? What does that mean? He had taken on a novice—named Adam, appropriately enough—but he was young and not fully tempered, and now Lucius knew he would not be able to complete his work with the boy.

The smacking stopped. Lucius followed his eyes to the door he stood in front of now. The world above, the Psalms and Pater Nosters were far away as he read the Runes on the stone door. He had entered it before, many times, and read the stones therein. Every night, while the abbey slept, he had read and recited and …

Runes wilt thou find, said the door, in its scratchy tree-limb words,

and rightly read,

of wondrous weight,

of mighty magic,

which that dyed the dread god,

which that made the holy hosts,

and were etched by Othin …

And now Lucius heard his voice, as his mouth opened and spoke, and the voice was strange and mixed, his own and another—an old, sad, angry voice, as much from deep within the rock as from his head—and he read and answered the questions there that only he, so far, could truly answer.

Know'st how to write, know'st how to read?

Yes …

Know'st how to stain, how to understand?

Yes …

Know'st how to ask, know'st how to offer?

The voice was fuller now, more the ancient and less his own.

Yes …

The voice rumbled now, ancient and bestial.

Know'st how to supplicate,

Yes …

Know'st how to sacrifice?

Yes! The voice within Lucius of Avranches shrieked and howled, deep in the bowels of the Mont, so that he thought his own poor, chaste body would rip asunder.

Then the door began to shake and rumble and pull back, sliding away. His body stepped forward as he saw the top of the doorway slide past his forehead and light filled the ancient room.

Strange shadows danced on the wall and Lucius could see what was carved there, had seen it many times, but it had never shone so dark and clear, the figure in the wall with the horns on his helm, with his whole body bound at the bottom of a pit, bound in entrails, trembling in agony as the venom of the world-snake dripped on him and stung him. He would be bound there, Lucius knew, all the texts said, until finally he would break his bonds and come forth, and sailing in a great ship of human nails would he go forth to bring about the end of the world. Ragnarök. The end of all things living and the end of the gods.

"This is the fate," said the voice, ancient and sad and angry, "of Loki."

O O O

Show me what you have to tell,

O Spirits, by this sacrifice …

In the near-coastal city of Avranches, in Normandy, a sorceress squatted on a dusty floor and peered into the fire that burned in the corner of her tiny house. She smirked to herself and rubbed her arm, which still bore the marks of the flame. She had burned her arm a bit along with the sacrifice in hopes that the pain might clarify the visions she was having. Outside the only window in the house Viollette could see the faint glow of candles in the cottages of the town below, and the surf rolled in her ears, now loud, now soft.

The spirits had abandoned her. Now! Now, of all times, when she was having these visions and she needed their guidance most. Had she not served them well? Had she not risked life and limb time and time again when the damned folk of the village had come so close to catching her and burning her at the stake?

By this innocence wasted, show me

By this death and new life …

Of course, Viollette had always expected to burn at the stake, it was simply the way they did you in when they caught you. But now, and for the past several days, a new fate had been revealed to her, and then her sight was taken from her, teasing her, as if after all these years of service she had no right to know her own future. Live by the magic.… Damn them all!

She snarled and hissed at the town. She knew what they were about, at least, knew that they had even gone so far as to report her to the abbey at Mont Saint-Michel, just across the bay.

Just now, a moment before she lost the vision and tried to bring it back, she had sensed some great coming. What was it? It had not come to Viollette, and yet she felt certain that it would have something to do with her. The crackle of the fire laughed in her ears spitefully.

Show me …

She looked into the fire and concentrated on the blackening bones there, on the simmering fat that popped and snapped on the bricks. How could it not work? The child had been precious enough, and damned hard to come by, and yet she saw nothing.

And then she heard a sound. She stared intently at the fire before realizing that the sound was quite natural, and had come from outside. What she heard was the murmuring of men. She looked out the window at the town and saw the same lights.

And then she realized that those lights were moving, torches, not candles. Viollette sprang up, looked out the window, and gasped. There was a line of dark figures, townsfolk, carrying torches aloft, coming up the hill. She turned about and looked at the fireplace. Damn them! Not now, there was too much she did not know! There was power about!

Now she could hear the chanting of the procession, for that was what it was.

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want …

She stared, mesmerized for a second as the flames briefly lit the faces of the procession and made strange, skeletal shadows on their faces. They saw her. This did not increase their speed; they stayed steady.

Fly!

Viollette whirled around again and looked at her books, trying to decide if she could take any of them with her. No, no, no, you'll get away, you can come back for them.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures …

She took a breath and stepped away from the window to the door of the small house, hoping she would not be seen. She slid the bar out of its place and pulled the door open slightly. Good. The door faced slightly away from the town. The night was dark, the moon but a waning crescent, shedding little light. Let them have their damn Psalms. She opened her door all the way and stepped out.

Viollette looked back again at the cottage and then shut the door. She would have to go along the front wall to the back side of the house and away into the woods. Viollette visualized all parts of this daring escape as she sprang two feet away from the door and gasped as she struck something.

It was a man. No sooner had Viollette run into him than she felt her arms clasped tightly by the figure in the dark. She whipped her head around to see the lights of the procession growing closer.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death …

Viollette's arm hurt where she had uselessly burned it and she hissed, trying to scratch her assailant, but she knew she was finished. Too stupid, how could I be trapped by these stupid …

The Twenty-third Psalm was echoing bitterly in her ears and she could only see the fires of the torches as she was surrounded, and all time ceased to be real to her. People said things that she did not understand and some that she did and some things that might have shocked her if she was like them.

The witch, the witch killed our …

Yes, damn you all, yes, I'm a witch, and I'm damned proud of it.

She felt herself go limp, tired of fighting, as she was dragged back into her house, and the great, dark shapes of angry little men with their hollow eyes burning at her only imprinted in her mind that she was going to die and she had never learned what it was she wanted to know. All those years, all those years in the service of the black arts and nothing to show in the end.

Was it real, Viollette wondered, was this really it, was she really being tied hand and foot to her own chair? Spirits, they're going to burn me in my own house.…

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies …

Were those sounds of breaking wood and whispers and shouts and the Twenty-third Psalm really there, sounding as if they were miles away? What had she learned?

Were those really her books at her feet, and really a torch licking like a hellhound at their pages, as they stared at her and dared her to read them one last time?

Thou anointest my head with oil …

Her skin was peeling away from her legs and she could not hear the sounds anymore, could hear nothing but the faint pop and sizzle of her own flesh as it curled black away from her bones. Her heart was pounding as she bit deeply into her lip and tried to taste the blood, to gain any sort of control of her own senses. There was power about! What was it? Show me, damn you, I want to know!

Show! she screamed, and was not sure if the word poured out of her burning mouth or her mind, but as the flames licked up and engulfed her, she saw a book at her feet, charred but not yet burned, that somehow fell open to her answer.

And Viollette could no longer hear the Twenty-third Psalm as she read the page with her searing eyeballs and cackled and screamed. It was the Voluspa Hin Skanna, The Short Seeress' Prophecy, and all she could make out was the one stanza that glowed but waited to be read before disappearing to mix with her ashes, telling her part:

A half-burnt heart which he had found—

it was a woman's—ate wanton Loki.

With child he grew from the guileful woman …

Viollette screamed as her eyes disappeared and she saw in her fading mind the last line:

Thence on earth all monsters sprung.…